The best route to the lakes and mountains

| Title | Map of the Boston, Concord, Montreal & White Mountains Railroad and Its Principal Connections |

| Creator | Rand, Avery & Co. |

| Year | 1882 |

| Dimensions | 60 × 28 cm |

| Location | Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library |

Up until the early nineteenth century, most Euro-Americans treated the mountains of northern New England as a barrier to be crossed or as wasteland to be avoided. Beginning in the 1830s, however, a new Romantic attitude towards a supposedly untouched nature had begun to turn these landscapes into symbols of beauty and wonder, and, by the time of the Civil War, the mountains and lakes were home to a full-blown tourist industry. () Railroads were a symbiotic part of the development of this tourist industry; they made travel to the region feasible and fast, and, in turn, the railroad companies took a lead role in promoting these areas as tourist destinations.

The Boston, Concord, and Montreal Railroad was chartered in 1844 to connect two disparate sections of New Hampshire, the lowland region that stretched up the Merrimack Valley to Concord, and the Upper Valley of the Connecticut River. It was difficult to complete a route through hilly country, through an area with few prospects for paying customers, and it wasn't until 1853 that the line was completed from Concord to Wells River, Vermont, where it met the Connecticut & Passumpsic Railroad connecting north to Canada. ()

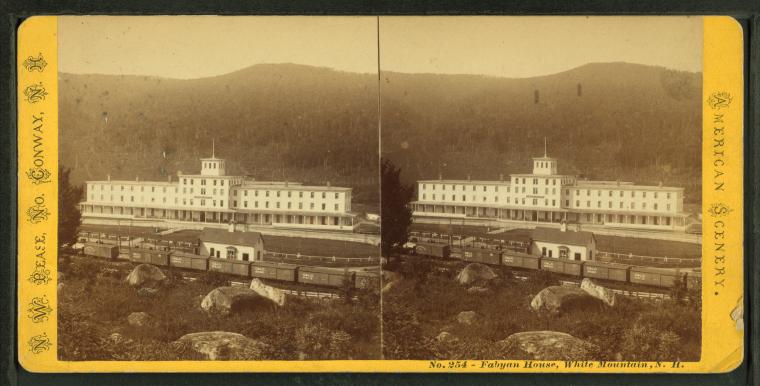

By 1882, when this map was published, the sparse population and rugged terrain of northern New Hampshire had gone from being one of the railway's biggest liabilities to one of its biggest assets. To advertise its scenic route through the mountains, this map stretches New Hampshire and Vermont. In reality, the distance between Concord and Lancaster is only about twice as long as the distance between Boston and Manchester, but in this map the distortion makes it more than three times as long. It gives prominent billing to the many stops where tourists might want to stop for a summer retreat, like the Weirs on Lake Winnipesaukee (spelled “Winnipeseogee” here), the Profile House in Franconia Notch, or the grand Fabyan House hotel on the railroad's Mount Washington branch. From there, tourists could ascend to New England's highest peak on the Cog Railway.

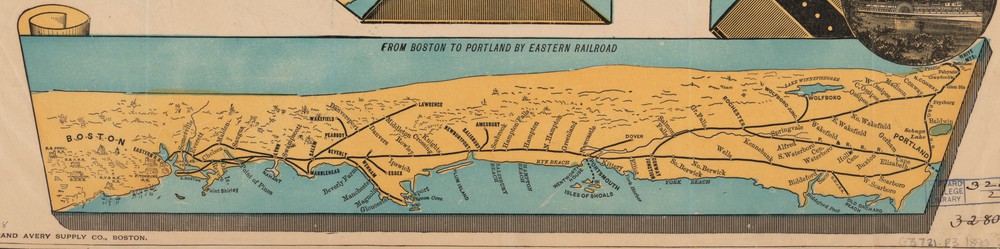

By emphasizing the western approach to the White Mountains, this map also withers away competing routes, such as the lines of the Eastern Railroad and Maine Central Railroad that entered the mountains from the other side. By contrast, this 1890s map from the Eastern Railroad flips the perspective entirely, showing the line's coastal route from Boston into Maine and from there to the White Mountains—with the Boston, Concord, and Montreal invisible just over the horizon.

Like many train maps of its day, this one brags of the line's convenient services, touting palace cars and air brakes. The Boston, Concord, and Montreal even appended their most famous tourist destination to the company name, becoming the “Boston, Concord, Montreal, and White Mountain Railroad” to strengthen the route's association with the Whites in the public eye. The text surrounding the map notes that the line offered “the only route” that would allow tourists to reach destinations like Twin Mountains or Plymouth without a change of cars, as well as the “the most direct route” from any of the cities south and west of Boston.

Bibliography

- Caswell 1919

- C. E. Caswell, Boston, Concord & Montreal: Story of the Building and Early Days of This Road (Warren, N.H.: The News Press, 1919). https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.hb10ma

- Brown 1995

- Dona Brown, Inventing New England: Regional Tourism In The Nineteenth Century (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995). oclc:920288128