War games

| Title | War Maps of Cuba, Porto Rico, and the Philippines |

| Year | 1898 |

| Dimensions | 24 × 64 cm |

| Location | Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library |

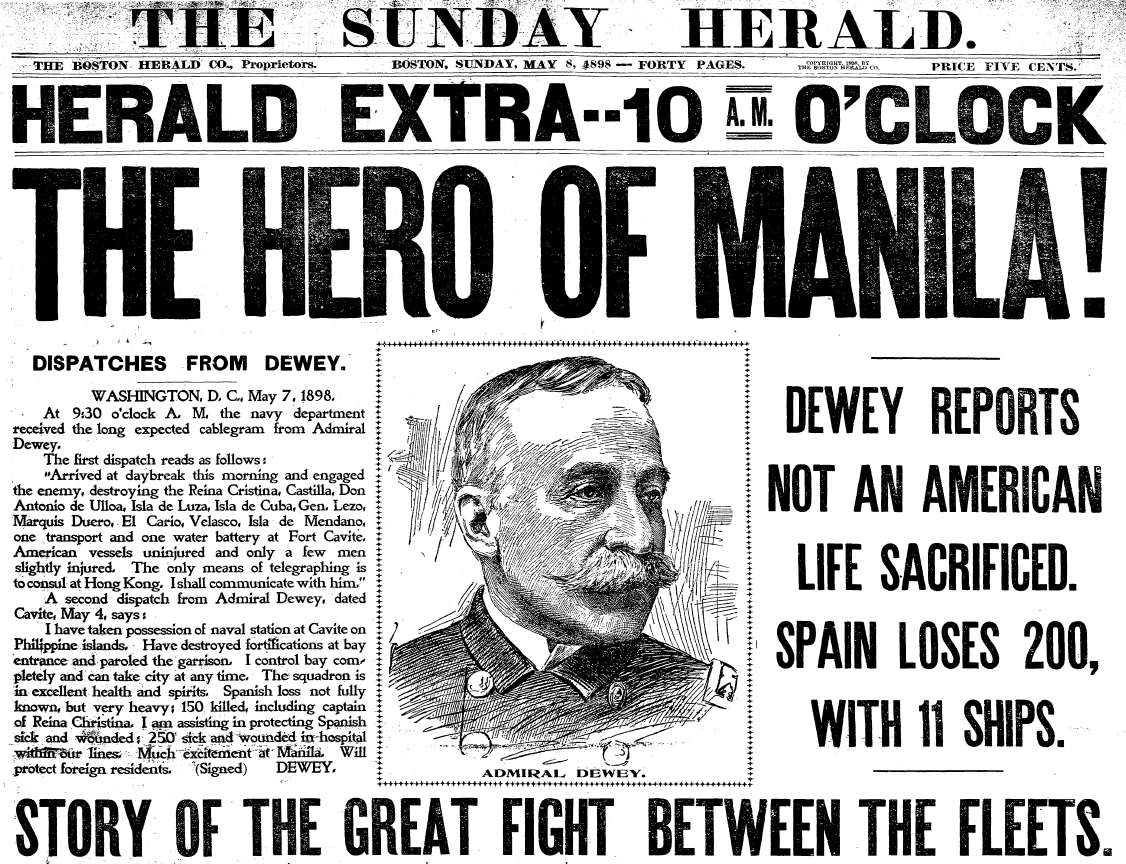

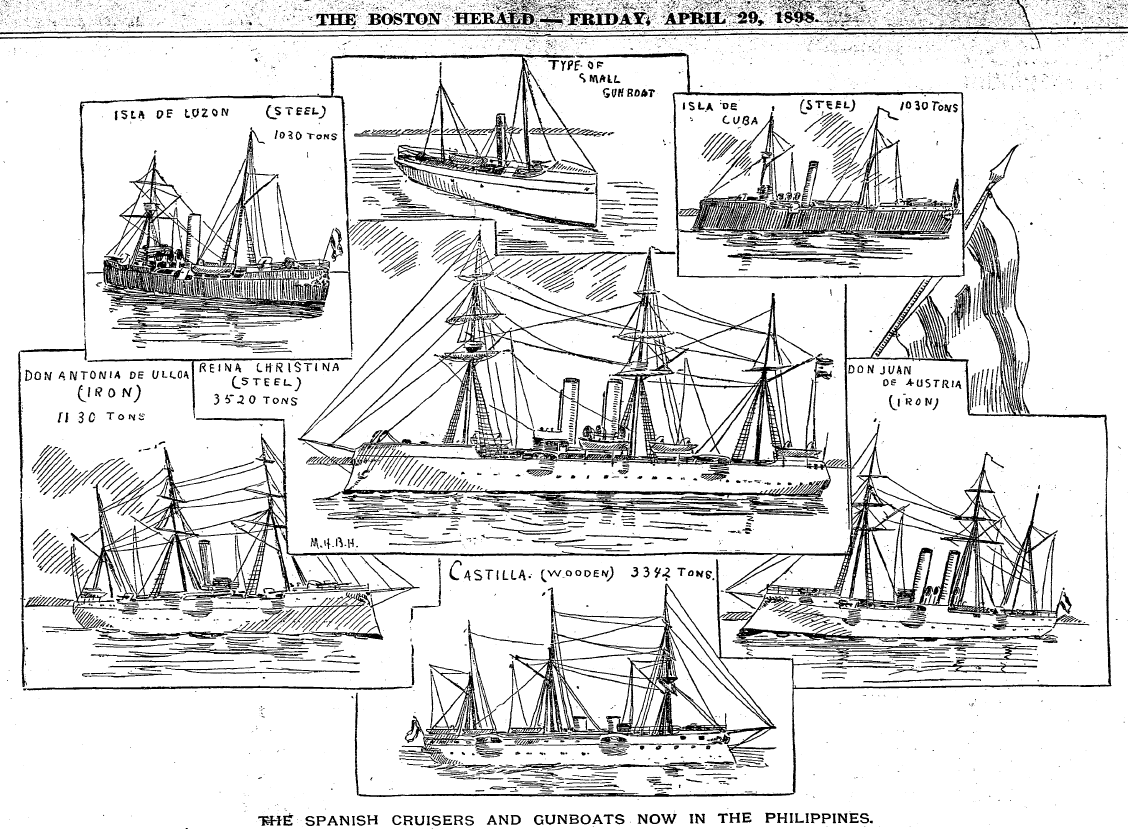

On May 8, 1898, the Boston Herald continued their coverage of what would come to be called the Spanish-American War with an article about a battle on May 1 in Manila Bay, the Philippines Islands. During the battle, the Asiatic Squadron of the U.S. Navy, under the command of Commodore George Dewey, destroyed the Spanish squadron of cruisers and gunboats under Admiral Patricio Montojo y Pasarón ().

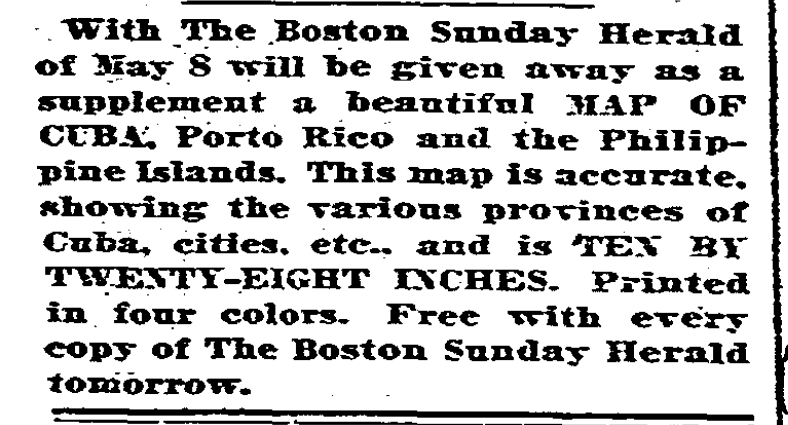

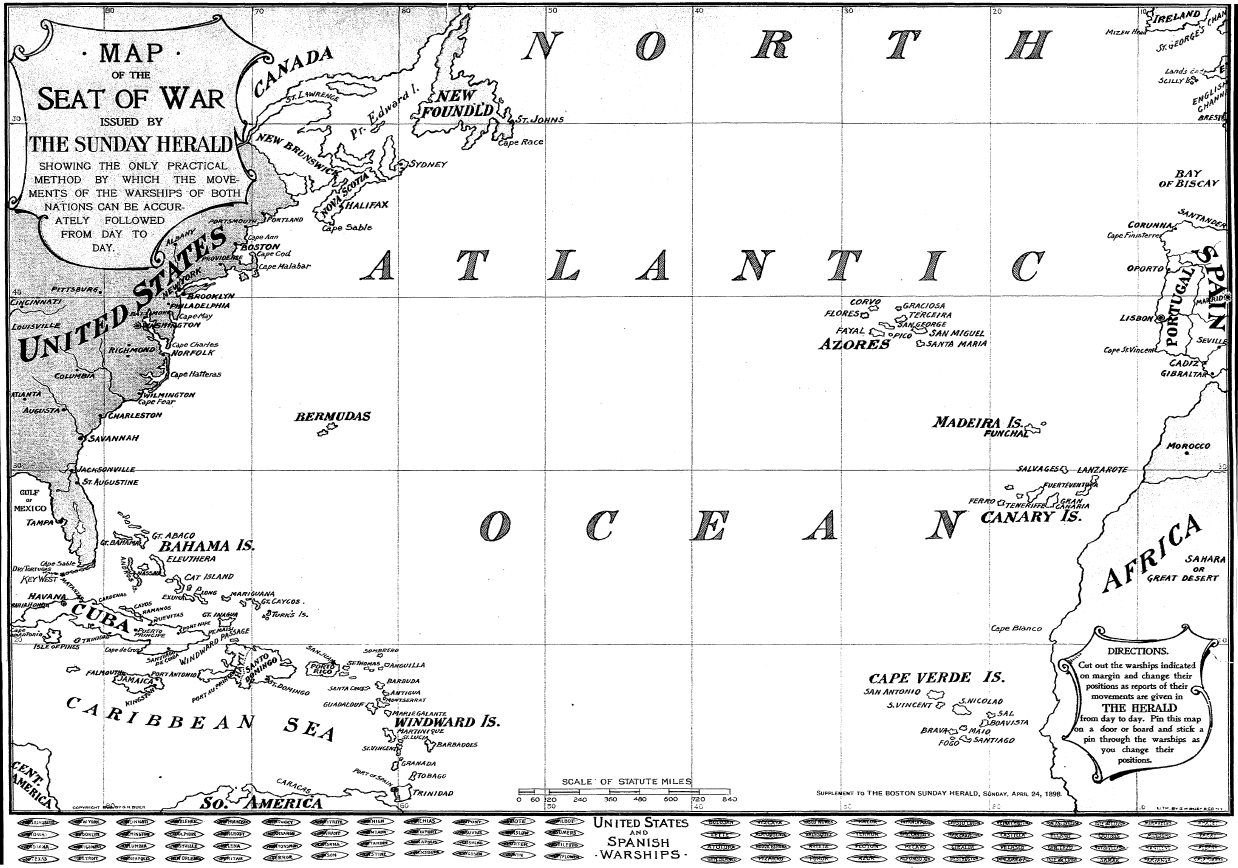

According to the paper, Bostonians responded by displaying “every sort of patriotic demonstration” including “flag-raising” and other celebrations. The practice of flag-raising was echoed in the map that was included as a supplement in that Sunday’s paper. The map was intended to allow subscribers to chart the war by cutting out the miniature American, Spanish, and Cuban flags, provided in the margins, and pinning them on the map ().

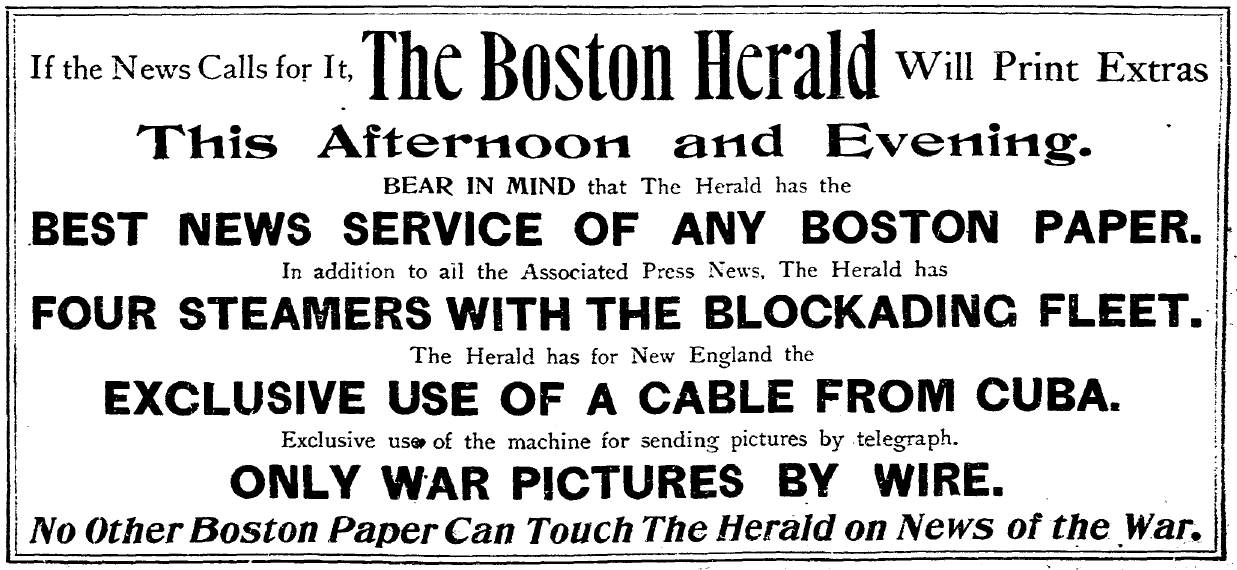

The Herald map was reminiscent of military strategy planning boards and allowed subscribers to feel as though they were maneuvering the war from the position of the generals and admirals. This type of interactive map was indicative of ways in which the mass media encouraged readers to follow the developments of the war closely, and even to participate. In many ways, knowledge of the war became equated with patriotism. The Herald promised to provide knowledge in the form of “accurate” maps and the “best news service of any Boston paper” particularly in regard to war news.

Subscribers would have been familiar with some of the gunboats and cruisers involved in the battle in Manila Bay if they received the paper two weeks earlier. On Sunday, April 24, the Herald published a similar map. The map included the Atlantic and Caribbean, but rather than flags, it provided U.S. and Spanish gunboats and cruisers that were meant to me pinned into position on the map, or removed if destroyed. The map indicated that it was “the only practical method by which the movements of the warships of both nations can be accurately followed from day to day.” () It also promised that day to day reports of their movements would be given in The Herald.

A few days later, they printed drawings of the some of the Spanish gunboats and cruisers that were stationed in the Philippines—many of which were later involved in the Manila Bay battle. The Herald also frequently mentioned President McKinley’s “war office” maps when discussing the President’s plans. Maps became synonymous with military strategy and, in later months, claiming territory.

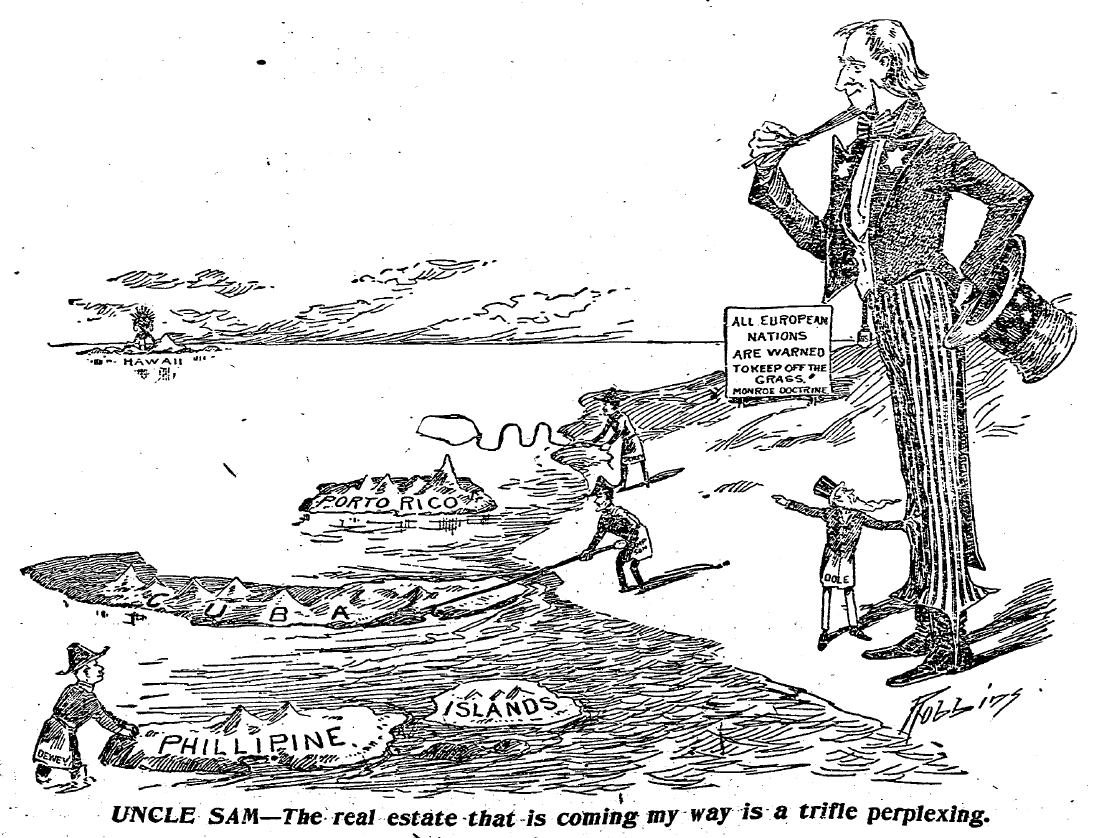

In an article on June 27, the Herald reported that the President spent much of his time in the “war room,” in order “to be near the telegraph and the telephone, or to consult the map of the world, on which alone the future imperial colonies of the United States can be studied, or the large maps of Cuba, showing every detail, prepared especially for him by the war and navy departments…” () Maps were used as instruments of war and persuasion. Descriptions of “accurate” and “detailed” maps reassured Americans that their leaders had the information necessary to win battles, compelled them to purchase newspapers and maps that would allow them to participate in the developments of the war, and strengthened their belief in the nation.

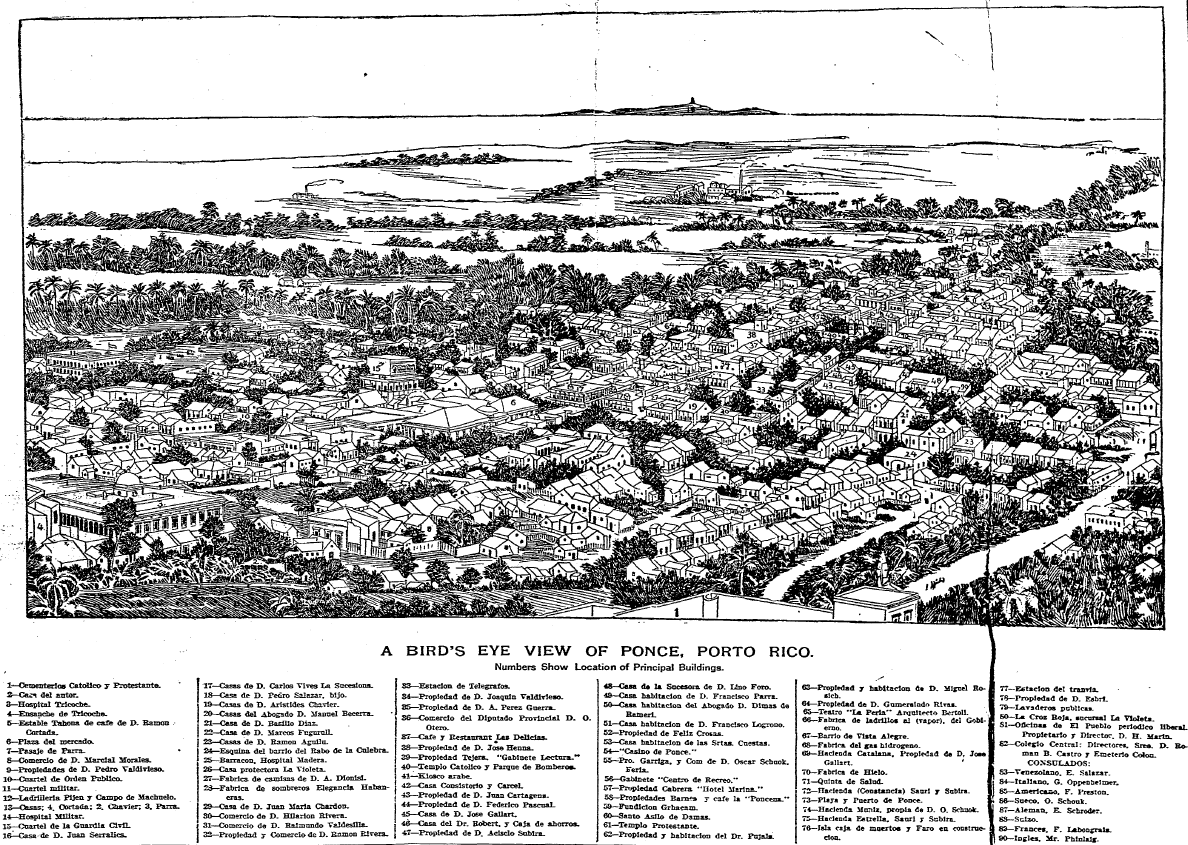

Articles titled “Cuba Free; Porto Rico Ours” and “Spanish flag must vanish from the Western Hemisphere” reinforced the connection between maps and empires and reduced regions to places on a map. This bird’s eye view of Ponce, Puerto Rico, was published as U.S. troops occupied the city. The next day on July 28, General Nelson Miles made an announcement in Ponce that claimed that the U.S. intended to extend a “banner of freedom” through military occupation of the island.

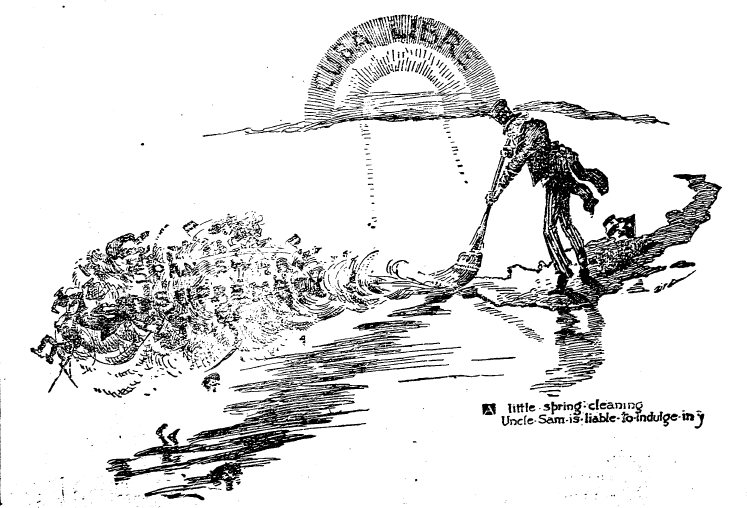

Although Spanish-American War only lasted a matter of months, the media coverage of the conflict made patriotism and imperialism topics of everyday discussion and precipitated the mass production of flags, maps, and other propaganda. The majority of the Herald’s advertisements, cartoons, stories, songs, drawings, maps, and articles referenced the war or themes of patriotism. In the final months of the war, articles often lauded America’s status as an imperial power while still perpetuating U.S. claims of liberating other nations from Spain’s oppressive dominion.

Bibliography

- Herald 1898b

- “Dewey and Manila: One Name and One Place on Every Tongue,” The Boston Herald (8 May 1898): 6.

- Herald 1898a

- “Hero of Manila,” The Boston Herald (8 May 1898): 1,4.

- MacFarland 1898

- Henry MacFarland, “Strain of Wartime,” The Boston Herald (27 June 1898): 2.