Truth as a Social System

How do we know whether something is true or not? Sometimes we can compare a claim about what is true to the evidence of our own senses. But the world is too large, too detailed, and too distant to check every truth for ourselves. Instead, much of what we accept as the truth is based on social systems of trust and belief, and on forms of evidence that gain their validity from the status of people and institutions.

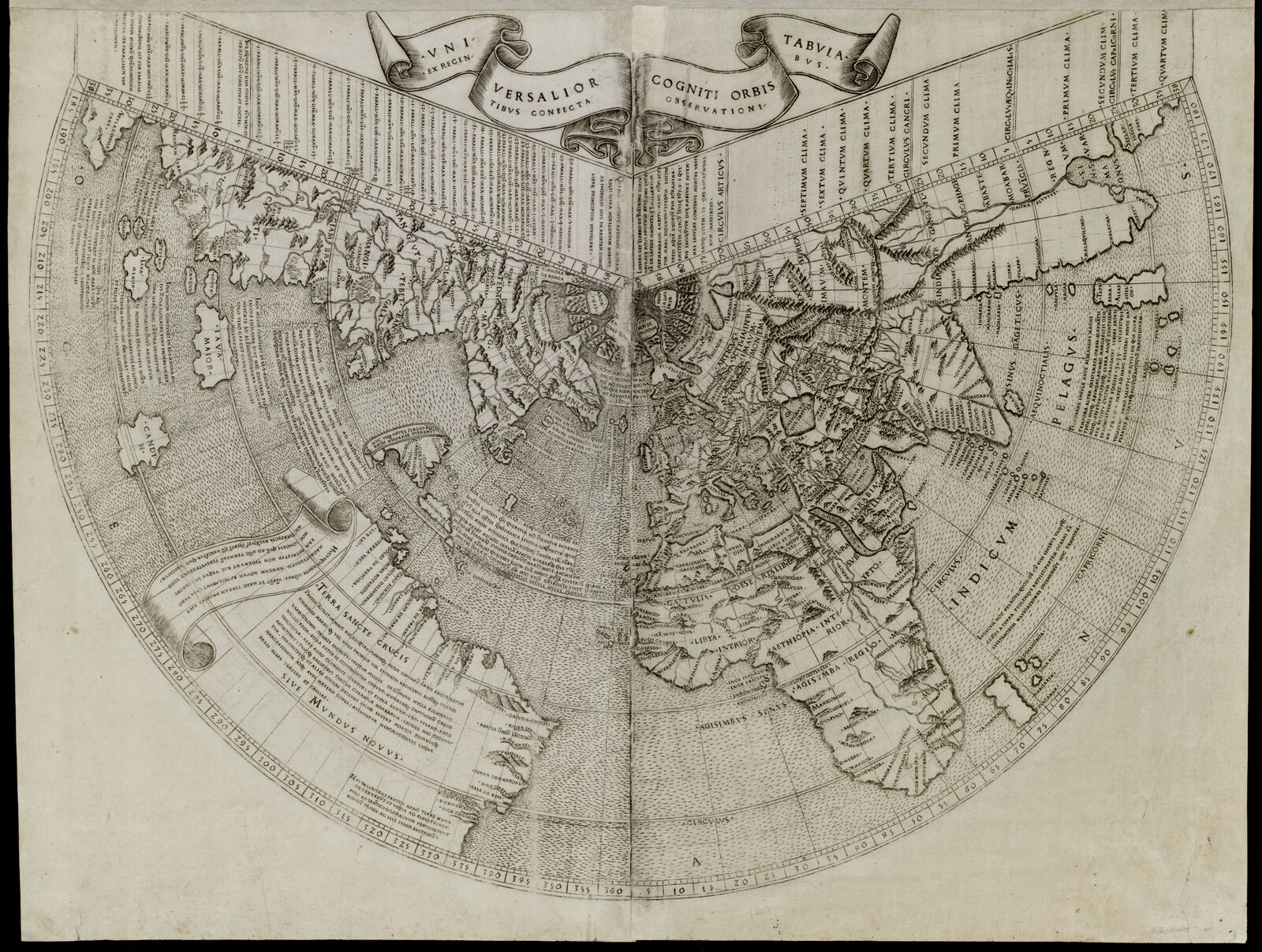

For European scholars of the early Renaissance, the most authoritative picture of the world was the one laid out by the geographer Claudius Ptolemy in the second century. Ptolemy's Geography depicted the world divided into climatic zones, with the continents known in classical antiquity centering on the Mediterranean. But by 1507, when the Dutch cartographer Johannes Ruysch published this map of the world, the Europeans had stumbled into the Americas, throwing Ptolemaic geography into doubt. This map shows a struggle to reconcile two competing versions of the truth less than two decades after Columbus's voyages. Ptolemy and the authority of ancient scholarship was still considered to represent an unimpeachable truth—but cartographers couldn't simply ignore the information that was coming from the other side of the Atlantic. Ruysch, like others, tried to bend the information about American continents to fit their geography into the system of the Ptolemaic worldview.

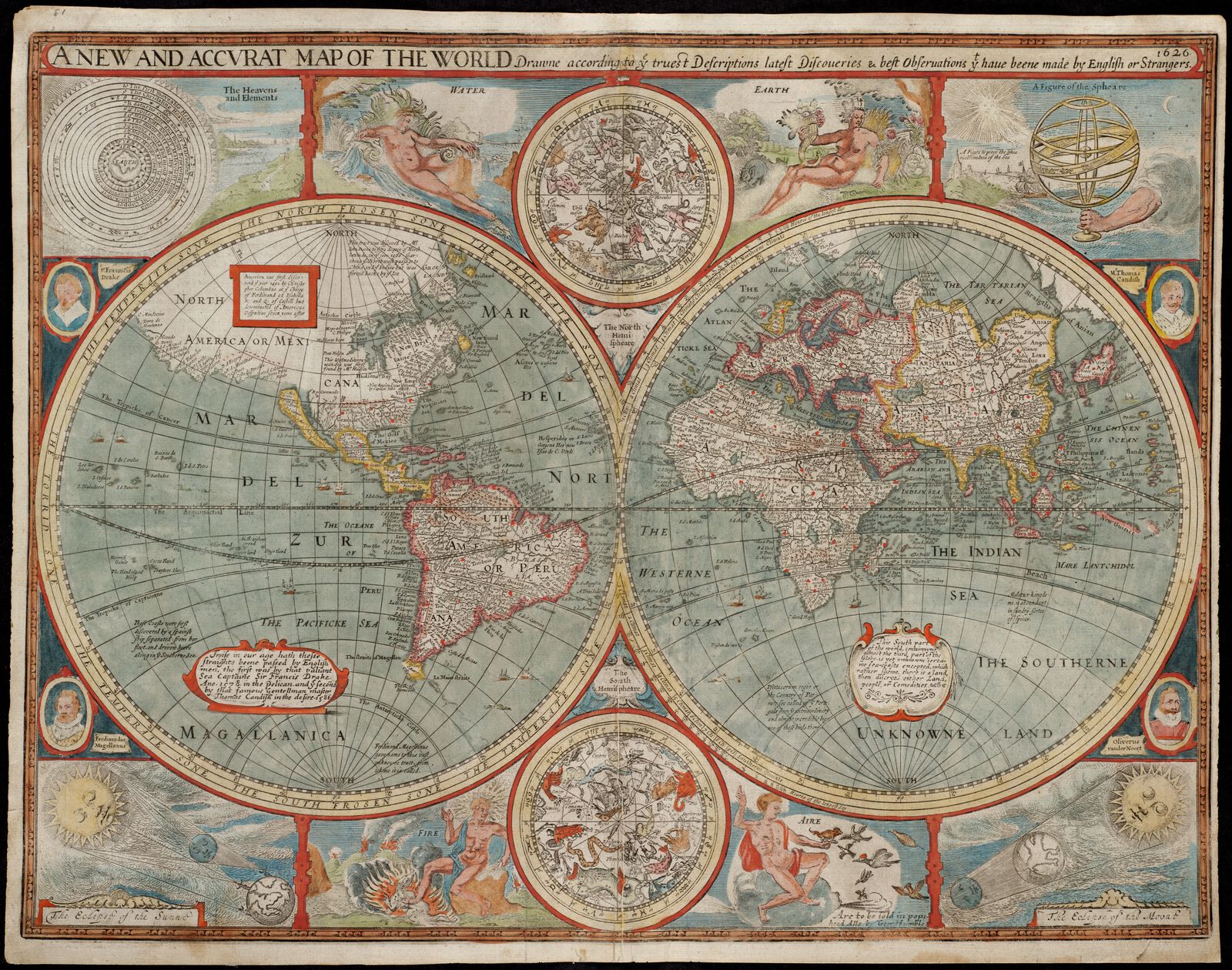

By the early seventeenth century, European exploration in the Western Hemisphere had confirmed that the Americas were in fact two large continents that existed completely outside of the framework of Ptolemaic geography. As voyages returned to Europe with new information about distant lands and oceans, cartographers scrambled to revise world maps to account for the new knowledge. The title of this 1626 “New and Accurat Map of the World” by John Speed advertises its own reputable status. The English word accurate originally meant “done with care”—suggesting that accuracy is as much about how a map was made as it is about what information it presents. Speed was a careful, diligent cartographer, but this map shows California as an island. Speed wasn't necessarily lying; he was just relying on what limited knowledge was available to English mapmakers. This map also shows another piece of truth that was undergoing a social shift at the time: a geocentric diagram of the planets orbiting the earth, published just at the same time that Galileo was fighting the church over whether astronomical observation or ancient authority held the most persuasive explanation for the universe's orientation.

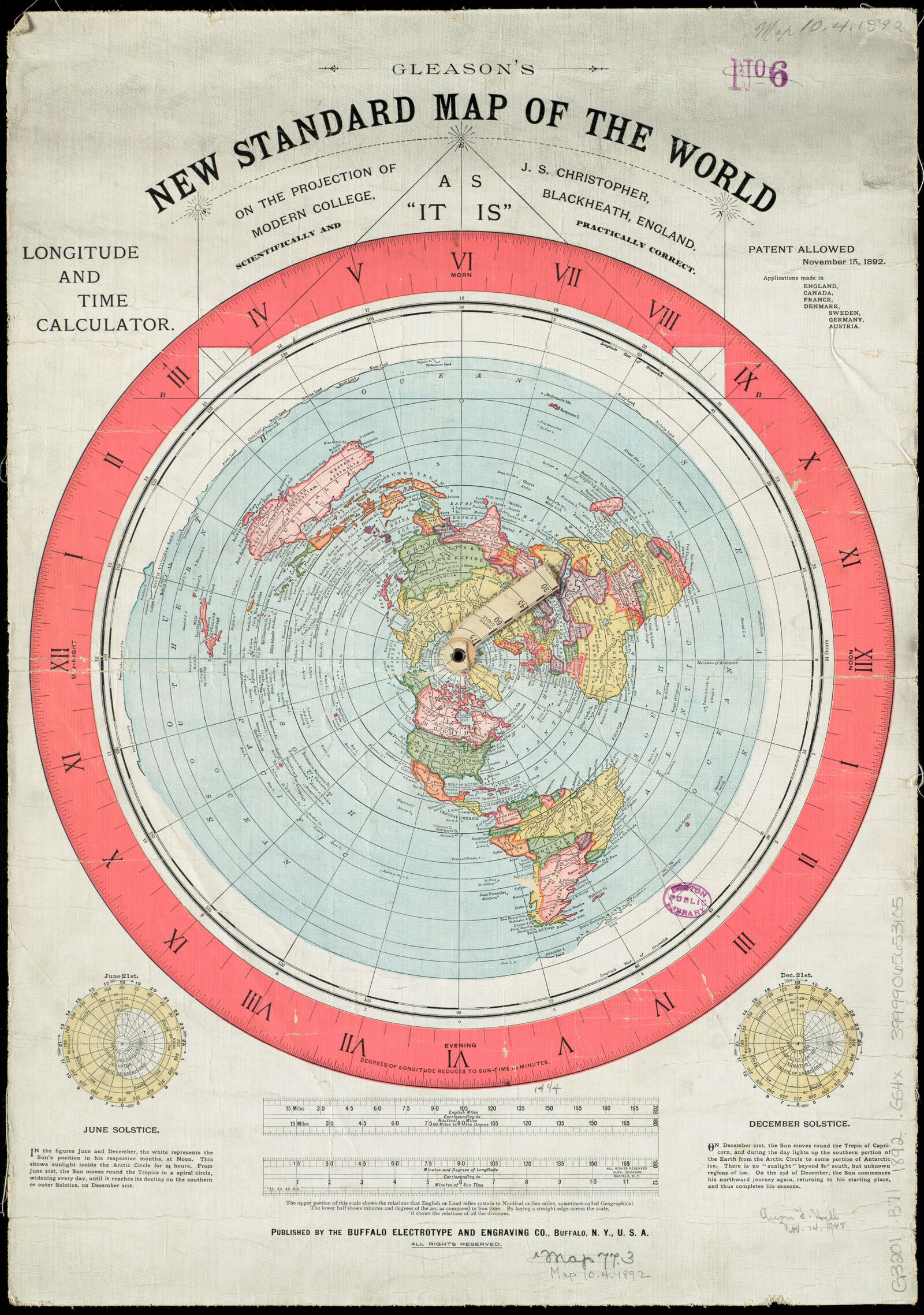

Today, most people accept the fact that the earth is round, the sun is at the center of the solar system, and California is connected to North America by land. Those truths rest upon a system of trust that relies on scientific evidence, demonstrative proofs, and, most importantly, the trustworthiness of the teachers and textbooks that assert these claims. You probably don't need to walk yourself from Phoenix to Los Angeles in order to be convinced that California isn't an island. For some people, though, belief points in another direction. This 1892 map that uses longitude as a time calculator is seen by proponents of the flat-earth theory as confirmation of this fringe geographic theory. It also happens to be one of the most-visited items in the Map Center's digital collections. The very fact that such an object appears in the collections of an institution like the Boston Public Library is a tantalizing sign to people who believe in conspiracies and cover-ups.

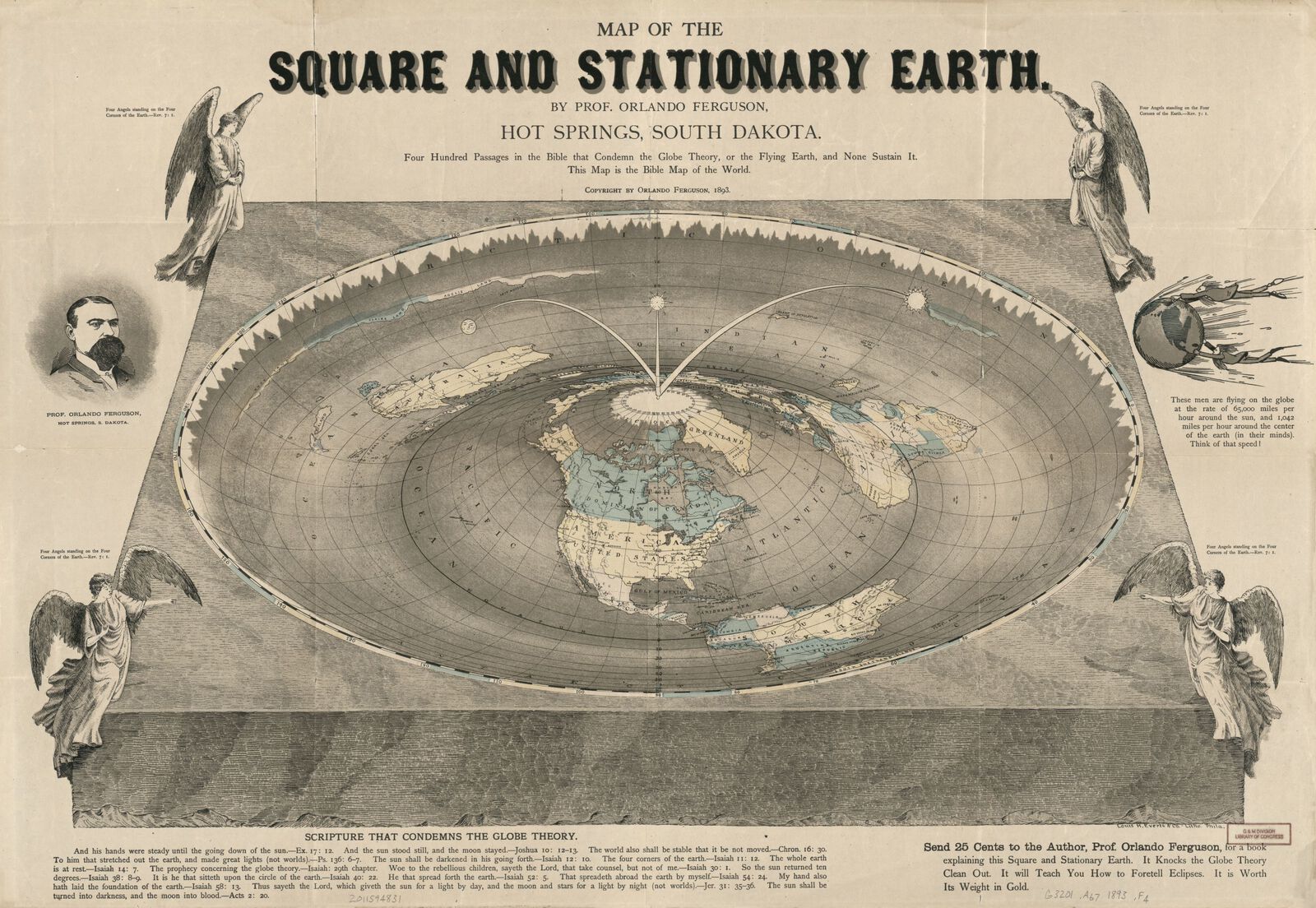

Published just a year later, this 1893 “Map of the Square and Stationary Earth” offers a different form of proof for a flat earth, pointing to a block of text with quotes from the Bible. The author, a self-appointed “Professor,” used a cartoon to show what he believed was the absurdity of the earth traveling around the sun at 65,000 miles per hour—surely people would fly right off!

What institutions earn our trust, and who do we believe? When the astronaut William Anders snapped this photograph of the Earth from the window of the Apollo 8 capsule, it captured the world's attention. Even though, by 1968, almost everybody accepted that the Earth was just one planet floating in space, a photograph like this one—which later became popularly known as Earthrise—provided an arresting reminder of the delicacy of the planet's ecological balance. Photographs like this one played a role in the environmental movement of the 1970s, and the prestige of a scientific institution like NASA, which had managed to put people on the Moon, gave these images a special power. Of course, some people clung to a suspicion that NASA itself was a hoax, and constructed elaborate arguments intended to prove that the space photographs were doctored.

words