The climatology of white supremacy

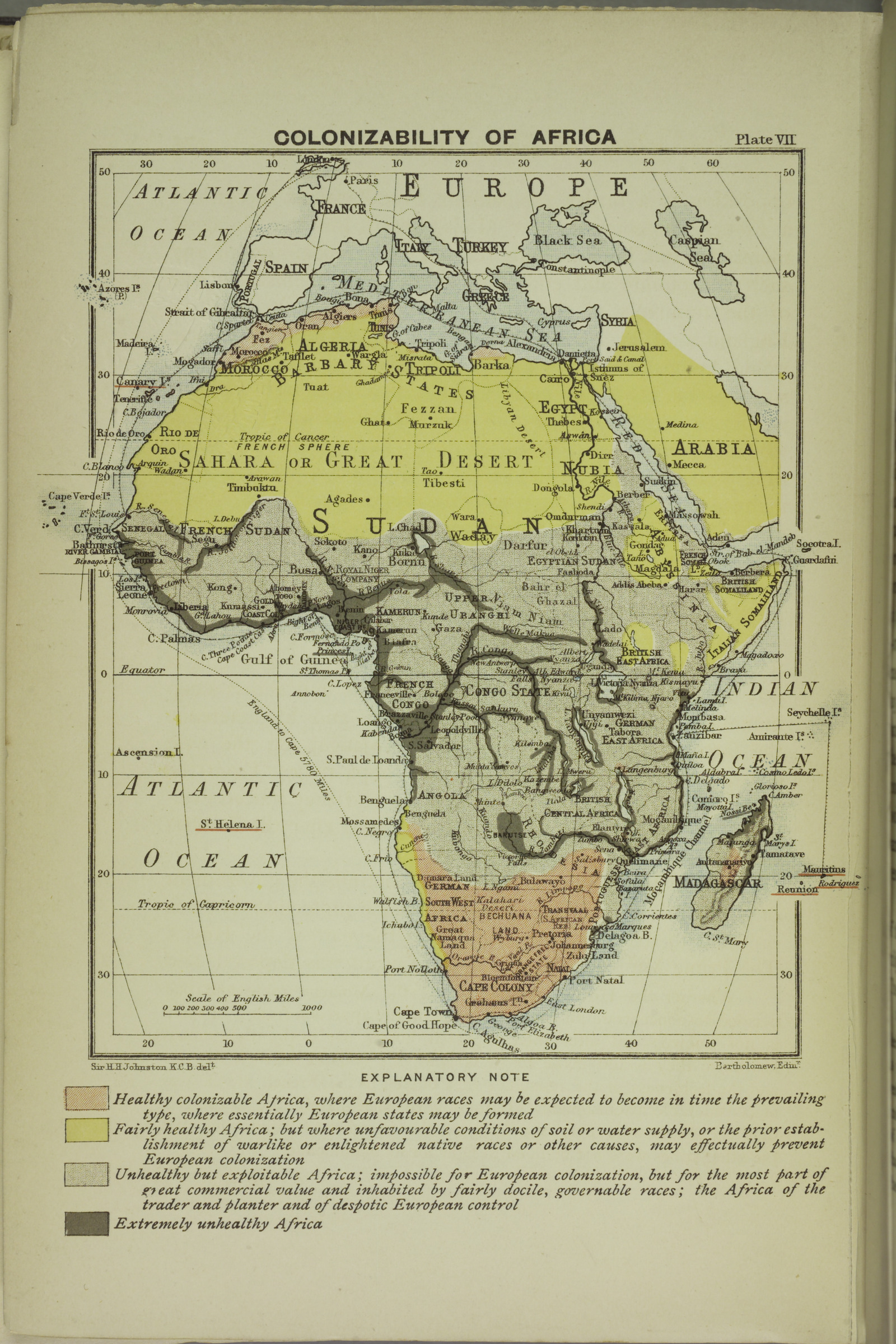

| Title | Colonizability of Africa, from A History of the Colonization of Africa by Alien Races |

| Creator | John Bartholomew (1860-1920) |

| Year | 1899 |

| Dimensions | 20 cm |

| Location | New York Public Library |

This Eurocentric map of the “Colonizability of Africa” was one of eight maps created by John George Bartholomew for Sir Harry Hamilton Johnston’s A History of the Colonization of Africa by Alien Races, published in 1899.

Johnston presented himself as an expert on the African continent citing his experience as a British colonial administrator and his studies of African languages as evidence of his expertise. He used this reputation to publish several books in which he espoused racial hierarchies and imperialist propaganda.

In his discussion of the “colonizability of Africa,” Johnston conflated climate classifications with racial categories to create his own “classes of territory.” Johnston divided Africa into four zones: “healthy colonizable Africa,” “fairly healthy Africa,” “unhealthy but exploitable Africa,” and “extremely unhealthy Africa.” As the titles suggest, however, these classifications had little to do with the “health” of the climate, and much more to do with the ease by which different regions could be subdued, with native populations pushed aside, and converted into territories for European settlers.

Johnston defined “healthy colonizable Africa” as the areas that were already colonized and under some form of European control. Johnston wrote that the “countries lying under the first category I should characterize as being suitable for European colonies, a conclusion somewhat belated, since they have nearly all become such.” Meanwhile, “less-healthy” territories were areas where Africans continued to contest European colonization, or “where climatic conditions and soil are not wholly opposed to the healthful settlement of Europeans, but where the competition or numerical strength or martial spirit of the natives already in possession are factors opposed to the substitution of a large European population for the present owners of the soil.” ()

Johnston also perpetuated myths common in settler-colonial narratives, including the idea that there was not a “dense native population” in “healthy colonizable Africa” and that certain climates made it possible for “Europeans to cultivate the soil with their own hands.” In reality, the vast majority of European invasions of Africa involved violent dispossession of profitable and populated lands and exploited African labor and resources. Johnston defends European exploitation with racist claims that Africans were “content to perform…many services which [their] bodily strength and indifference to health permit [them] to render advantageously.” Here Johnston reaffirms his racial coding of “health” to excuse the exploitation of black labor and uses it as another justification for the dispossession of African lands. Johnston predicted that “as the white population increases from thousands to millions it will tend to reserve to itself all the healthy country…and the black man will be pushed by degrees into the low lying unhealthy coast regions…” ()

Johnson concluded with a prediction that European invasion would not be threatened by a unified Africa, because he believed “it is difficult to conceive that the black man will eventually form one united negro people demanding autonomy, and putting an end to the control of the white man.” () Within a year of publication, however, W. E. B. Du Bois and other Pan-Africanists gathered at the first Pan-African International Conference, in London, in July of 1900, where Du Bois delivered a speech “To the Nations of the World,” in which he observed the racial inequalities of the “color-line” and demanded decolonization ().

Bibliography

- Johnston 1899

- Harry Hamilton Johnston, A History of the Colonization of Africa by Alien Races (Cambridge University Press, 1899) 244-281.

- Battle-Baptiste and Rusert ed. 2018

- Whitney Battle-Baptiste and Britt Rusert, ed. W.E.B. Du Bois's Data Portraits: Visualizing Black America, The Color Line at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, (Princeton Architectural Press, 2018).