Data comes from people

| Title | New Machine to Speed Up Statistics of Census of 1940 |

| Creator | Harris & Ewing |

| Year | 1940 |

| Dimensions | 11 × 13 cm |

| Location | Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division |

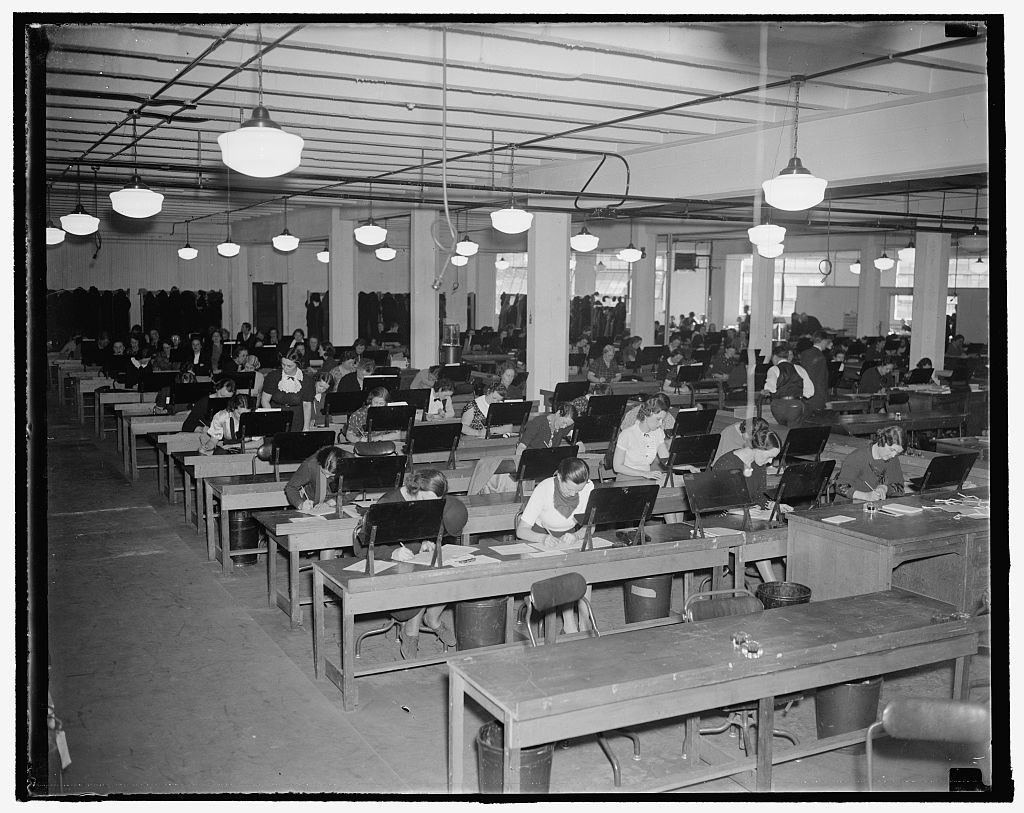

| Title | Tabulation of Unemployment Census Returns Begun in Capital |

| Creator | Harris & Ewing |

| Year | 1937 |

| Dimensions | 11 × 13 cm |

| Location | Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division |

| Title | Taking Census, 1920 |

| Year | 1920 |

| Dimensions | 11 × 13 cm |

| Location | Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division |

The United States Census Bureau hired thousands of enumerators and clerks to collect, organize, and tabulate the data needed to complete the 1920 and 1940 censuses. The U.S. decennial census was, and remains, an enormous and complex undertaking—one that required residents to provide answers to the enumerators’ questions and for census workers to make choices about how to interpret responses or silences and record them on the census schedule.

The nearly sixty page 1920 instruction booklet issued to enumerators provided information from who should be included, to how much time was allotted to complete each district, to the order in which city blocks were to be canvassed. The 1920 census schedule required enumerators to record answers to newly added questions about naturalization status, English proficiency, and “mother tongue or language of customary speech.” The Bureau’s preoccupation with immigration was also illustrated in the instructions for recording place of birth. Altered borders following World War I prompted specific instructions for enumerators to record the region or city of birth, rather than country, for residents who reported that they or their parents were born in Austria-Hungary, Germany, Russia, or Turkey ().

The degree to which enumerators were expected to record definite and comprehensive data is also evident in the 1940 instructions. Most enumerators were supplied with a map of their assigned district and directed to correct and update it as they worked. If the enumerator found that the map was “incorrect in any detail” they were to report the error or omission and make corrections by hand. The district maps symbolized dwellings with dots, nonresidential structures were designated by an “N,” and roads were represented by double lines. If any structures, roads, or labels were missing, enumerators were instructed to add them and if they were no longer in use or nonexistent, the enumerator was to cross them out. Dwellings were also supposed to be numbered in order visited and cross-referenced on the schedule.

While the census schedules were “absolutely confidential,” the district maps could be shown to residents in order to gather information about locations or uses of structures. The confidentiality of the schedules was essential to the Bureau’s goal of accurate and comprehensive data. If residents believed their answers were confidential, they were more likely to willingly give complete and detailed responses.

The instructions prompted enumerators to “explain that the information IS STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL, that it will not be available to any persons except sworn census employees, that it is to be used only for statistical purposes, and that no use will be made of it that can in any way harm the interests of individuals.” Similarly, the improved electromechanical tabulation machines were intended not only to accelerate the processing time, but also keep “the legible data … locked up in vaults away from prying eyes” after it was coded and punched into cards that the machine could decipher and tabulate, as the full title of the first image indicates ().

However, the confidentiality of the 1940 census was threatened in 1942 when the proposed Second War Powers Bill included a provision that would allow the Commerce Secretary, who oversaw the Census Bureau, to provide individual level census data to government agencies responsible for the “national defense program.” The proposed bill was drafted in the context of the administration’s plans for the forced removal of Japanese Americans from their homes on the West Coast and incarceration in concentration camps.

The House Judiciary voted in favor of the bill, including the census provision, on February 28, 1942, just nine days after President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which initiated the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans near the Pacific. The Second War Powers Bill was passed by the Senate and signed into law by the end of March 1942. The law was repealed in 1947 and the Census Bureau denied that it provided identifying information for use in the forced relocation and incarceration on Japanese Americans. However, scholars have cited evidence that the Census Bureau provided “very detailed small area tabulations” ().

The confidentiality of census data was not the only issue with the 1940 census. The Census Bureau also learned that the 1940 population was undercounted when it compared the number of men aged 21-35 as recorded by the census with the number of men recorded in the draft registration. The discrepancy was much greater for black men, who were undercounted by 13 percent ().

Bibliography

- Department of Commerce 1919

- Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Fourteenth Census of the United States January 1, 1920. Instructions to Enumerators (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1919).

- Department of Commerce 1940

- Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Sixteenth Decennial Census of the United States. Instructions to Enumerators: Population and Agriculture 1940, Form PA-1 (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1940).

- Anderson 2020

- Margo Anderson, “An Enumeration of the Population: A history of the Census” Insights on Law and Society 20, no. 2 (May 2020).

- Anderson and Seltzer 2007

- Margo Anderson and William Seltzer, “Challenges to the Confidentiality of U.S. Federal Statistics, 1910-1965.” Journal of Official Statistics, 23, no. 1 (2007): 1–34.