This article was supported by the Leventhal Center's Allmaps Research Fellowships, an initiative that was formerly supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities. To learn more about this initiative, read our blog post explaining the NEH grant's termination. To learn more about how you can support Allmaps and other tools like it, reach out to LMEC's Associate Curator of Digital & Participatory Geography.

What happens when fifty volunteers, a centuries-old map, and an open-source platform come together for a two-day mapping marathon?

In March 2025, Mapathon 1571 transformed the Bruges City Archives into a vibrant hub of historical discovery and digital collaboration. Blending archival research, innovative tools, and community participation, the event aimed to unlock the secrets of a remarkable sixteenth-century map and connect historical landscapes to present-day knowledge.1

The project emerged out of a collaborative effort to digitize the manuscript map of the Liberty of Bruges by Pieter II Claeissens. This map, covering a vast area of coastal Flanders and its hinterland, stands out for both its visual richness and its cartographic precision. Following its digitization, the Flemish Heritage Agency sought to integrate it into the national geoportals geoportaal.be and geopunt.be, making it publicly accessible and integrated into modern mapping tools.

This required more than high-resolution photographing shown to the left—it also meant georeferencing the map by anchoring it to modern coordinates. This process allows the map to be explored and analyzed as part of today's digital spatial infrastructures.

Towards georeferencing the Claeissens map

Georeferencing tasks like this are typically the domain of GIS professionals, due to formidable technical demands: specialized software, high-performance computing, and a solid grasp of geospatial frameworks. But in this case, the Claeissens map presented a challenge of a different kind. Covering more than 3,000 square kilometers at a scale of approximately 1:12,000, its detail far exceeded what a single specialist could realistically contextualize. While our prior research confirmed the map's exceptional accuracy, we also found that its full interpretive potential remained out of reach without situated local knowledge.

This became especially clear during an earlier attempt to georeference a lower-resolution version of the map, which quickly ran up against the limits of centralized expertise. In contrast, our Pourbus Troubadour lecture series—informal, participatory living rooms lectures across the region—revealed just how much micro-local historical, geographical, and toponymic knowledge existed among heritage enthusiasts. However, this knowledge is often highly fragmented, confined to individual memory or undocumented sources, and difficult to collect within formal workflows.

This led to our first central question:

How can we integrate rich but fragmented local knowledge into the georeferencing process, and do so in a way that is open, inclusive, and technically robust?

Here, the goals of the BLUE BALANCE project offered a timely convergence. One of its core ambitions is to increase public participation in the sustainable transition of the Flemish coastal region. Specifically, it aims to identify and study the evolution of coastal landscapes, not only as natural environments but as cultural and historical spaces. International research has shown that embedding time-depth into specific places, and revealing how landscapes have changed and endured, strengthens local attachment and can catalyze broader engagement with sustainability challenges. This brought us to a second, related question:

How can georeferencing historical maps help embed time-depth in the coastal landscape, and, in doing so, foster broader participation in heritage and sustainability efforts?

Mapathon 1571 became our answer to both.

The Technical Turn: Using Allmaps to Democratize Georeferencing

Before we could even start to think about encouraging people to share their knowledge about the local landscape and participate in the georeferencing process, the technical threshold needed to be lowered. This is where Allmaps comes in.

Allmaps is an open-source project aiming to make georeferencing, presentation and exploration of digitized historical maps easier. It consists of multiple apps, packages and workers (all published as free and open-source software on GitHub), which create a powerful yet accessible tool suite to make historical maps more visible and usable. To pull this off, Allmaps builds upon the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF). This set of standards allows different institutions to uniformly share high-resolution images via the internet. Furthermore, images can be enriched using a technical extension called annotations, like the Georeference Annotations that are specified by Allmaps. With an accessible web interface on top of the technical processes, Allmaps enables anyone with basic computer skills to link geocoordinates to scanned historical maps (Allmaps Editor) and present the warped results in a web viewer (Allmaps Viewer).

By eliminating the need to download specialized software, train on technical workflows, and host large image files, Allmaps opened up the georeferencing process for non-professional users—but working with Claeissens' map required an additional adjustment. Although Allmaps already supported "multiplayer" georeferencing on a basic level, working on the same map caused both technical and practical problems (for example, the numbering of ground control points is not always synchronized, or volunteers tend to work on the same areas).

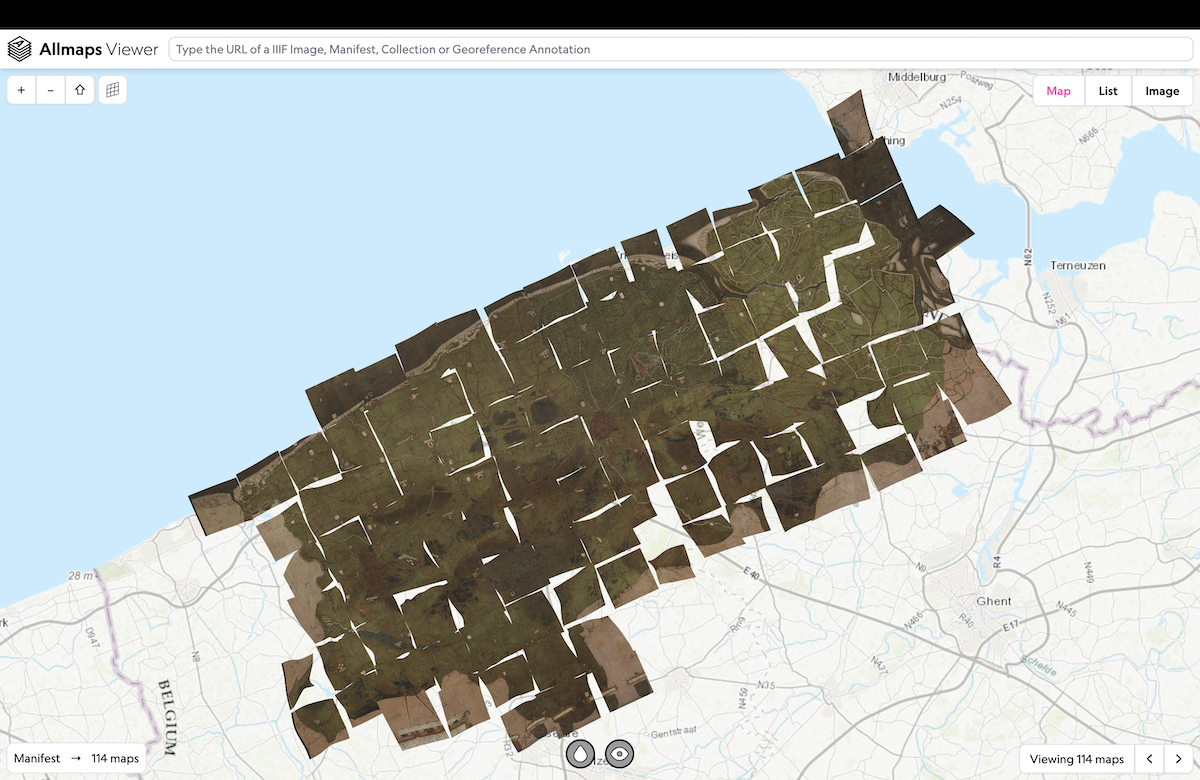

To manage a large group of people working on the same map, the image was therefore divided into 114 equally-sized tiles. Every tile of approximately 15 km² was presented separately in the georeferencing environment. In this way, the overall progress could easily be managed while volunteers could work independently without omitting certain areas or interfering with neighboring tiles. Based on the pixel coordinates of the original image, the ground control points added to the individual tiles could later be reassigned to the whole image in postprocessing. With some small adjustments, Allmaps thus provided a technical solution for volunteer-driven georeferencing.

The Social Layer: Collective Mapping as Community Practice

A technical solution alone does not guarantee a successful collective mapping event. Beyond the right tools, such collective mapping events require people, structure, and a shared momentum. That's why Mapathon 1571 was designed from the outset as a social and participatory event, not just a data-gathering exercise.

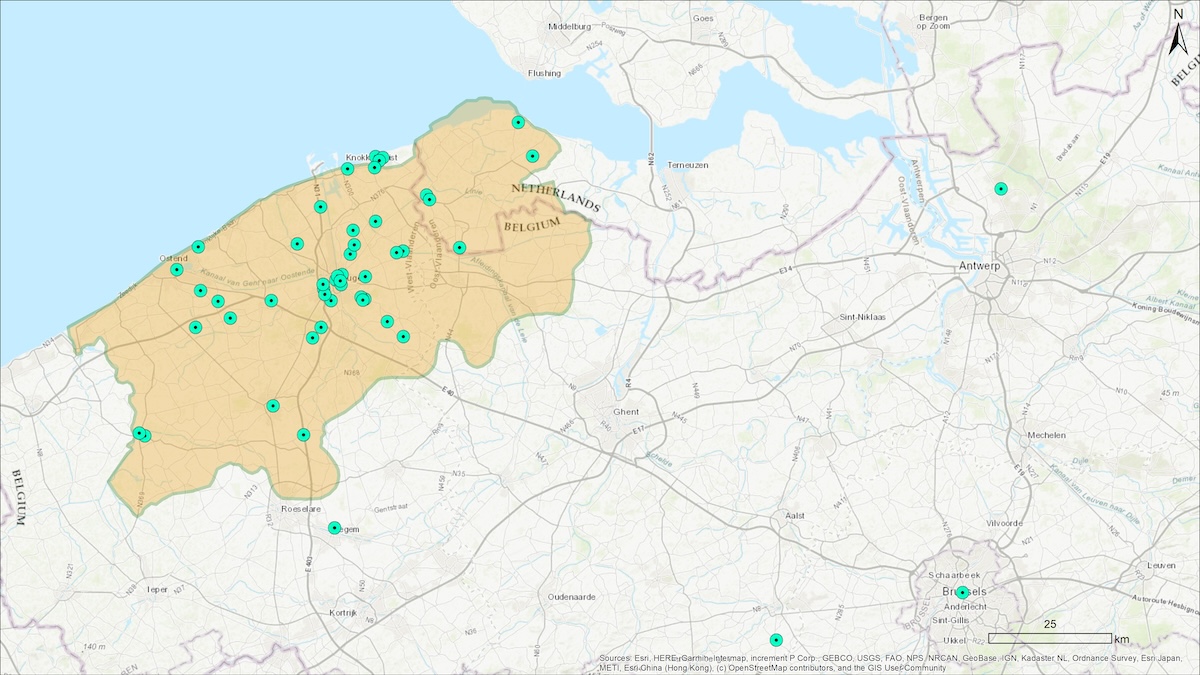

Over the course of two days, the Bruges City Archives became a shared workspace for 50 participants, selected from over 60 enthusiastic responses to our open call. The group included amateur historians, local heritage volunteers, map enthusiasts, students, and a handful of heritage professionals. While most participants lived within the region depicted on the map, a number of outliers (drawn by their cartographic interest) joined from cities like Brussels, Antwerp, and Aalst. All in all, the group represented a wide range of regional affiliations, backgrounds, and perspectives.

The points on this map correspond with Mapathon 1571 participants' places of origin.

Across a Friday and a Saturday, a different group of 25 participants followed the same program. The event opened on both days with a three-hour introductory session: participants introduced themselves and shared their areas of expertise and personal connections to the region or the maps, followed by a lecture on the Claeissens map and a group training in the Allmaps platform. Each participant then selected one or more tiles—15 x 15 cm. map sections, each corresponding to roughly 15 km²—and began georeferencing individually in Allmaps. Yet collaboration emerged organically: neighboring tiles sparked discussion, shared landmarks triggered memory, and peer-to-peer assistance unfolded spontaneously.

To organize and facilitate this tile-based approach, we also printed a scaled version of the map, onto which magnetized cardboard tiles—corresponding to the numbered Allmaps tiles—could be placed. This analogue tiles proved very instrumental. For us as organizers, it offered a clear overview of progress. For participants, it offered a tangible anchor and spatial point of reference; a way to get a physical grip on the digital map, which for many was still an unfamiliar environment. At the end of the day, each participant was invited to take "their" tiles home as both a keepsake and a token of ownership of the project.

Rather than enforcing strict productivity or output goals, the overall format emphasized connection, curiosity, and co-presence. Nevertheless, a quiet ambition to "complete" the map by day two certainly circulated. Long coffee breaks and communal lunches were deliberately built into the schedule to encourage informal conversation and exchange. Still, some participants became so absorbed in their georeferencing work that they chose to skip breaks altogether. As two cooperating participants recalled later on: "Because we were so intensely preoccupied with our work, we apparently forgot to join the communal coffee break in the afternoon."

Reflections from the field: Feedback and interviews

In between georeferencing sessions, we conducted 25 interviews with willing participants to gather feedback and reflections. In short 10-minute conversations guided by a fixed questionnaire, we asked participants about their backgrounds, their previous experiences with volunteering, their acquaintance with local history and cartography, and their motivations and expectations for joining the Mapathon.

We learned that contributing to a community-based cartography project using previously unfamiliar software sparked a sense of discovery and enjoyment for participants—something akin to Johan Huizinga's concept of historical sensation, or the emotional experience of encountering and feeling the past.2 As one participant explained, "The past is, of course, incredibly important. But we need to be able to place it in today's context. And that's exactly what new technology allows us to do; and I think that's fantastic."

Another reflected, "One could say that today, we have carried the Claeissens-Pourbus map into the 21st century!"

One 77-year-old participant was surprised about the effect it had: "I had never suspected it beforehand, but this is really addictive."

Participants provided constructive feedback on both the event format and application of Allmaps. Several participants on day one, for example, expressed a need for a more practically oriented explanation, noting that the initial presentation was somewhat overwhelming due to its technical detail. In response, we incorporated this feedback and adapted the introduction on day two to focus more clearly on hands-on use. Participants positively remarked the initiative helped to make history more accessible to non-specialists, offering them an alternative reference point beyond the more recent and commonly used eighteenth- and nineteenth-century historical maps.

What participants articulated in their own words was how the act of collaborative mapping helped them connect the past to the present in meaningful ways. By engaging with early modern cartography through accessible digital tools, Mapathon 1571 enabled a deeper awareness of historical continuity within familiar landscapes. This experience not only enriched personal understandings of place, but also illustrated how citizen-driven georeferencing can support wider engagement with the spatial dimensions of heritage and sustainability.

A Shared Map, Tile by Tile

By the end of the second day, the collective effort had exceeded expectations. All 114 tiles of the Claeissens map had been georeferenced. In several cases, tiles were even double-checked by peers for added accuracy and consistency. On average, each participant georeferenced 2.3 tiles, with individual contributions ranging from one to five. In total, approximately 1,800 ground control points were placed.

The post-processing phase began with merging the results from the 114 individual georeferenced tiles and reassigning their pixel coordinates to the original image as planned. This yielded a preliminary Georeference Annotation—the raw output of the Mapathon.

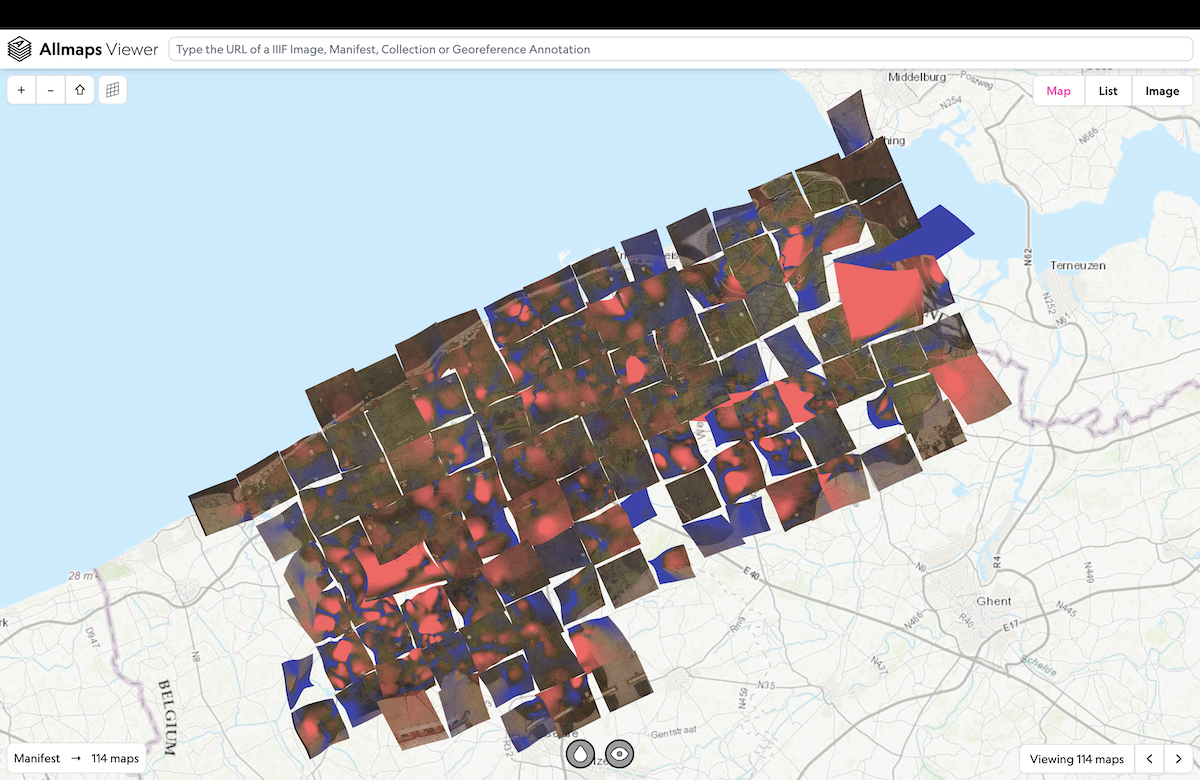

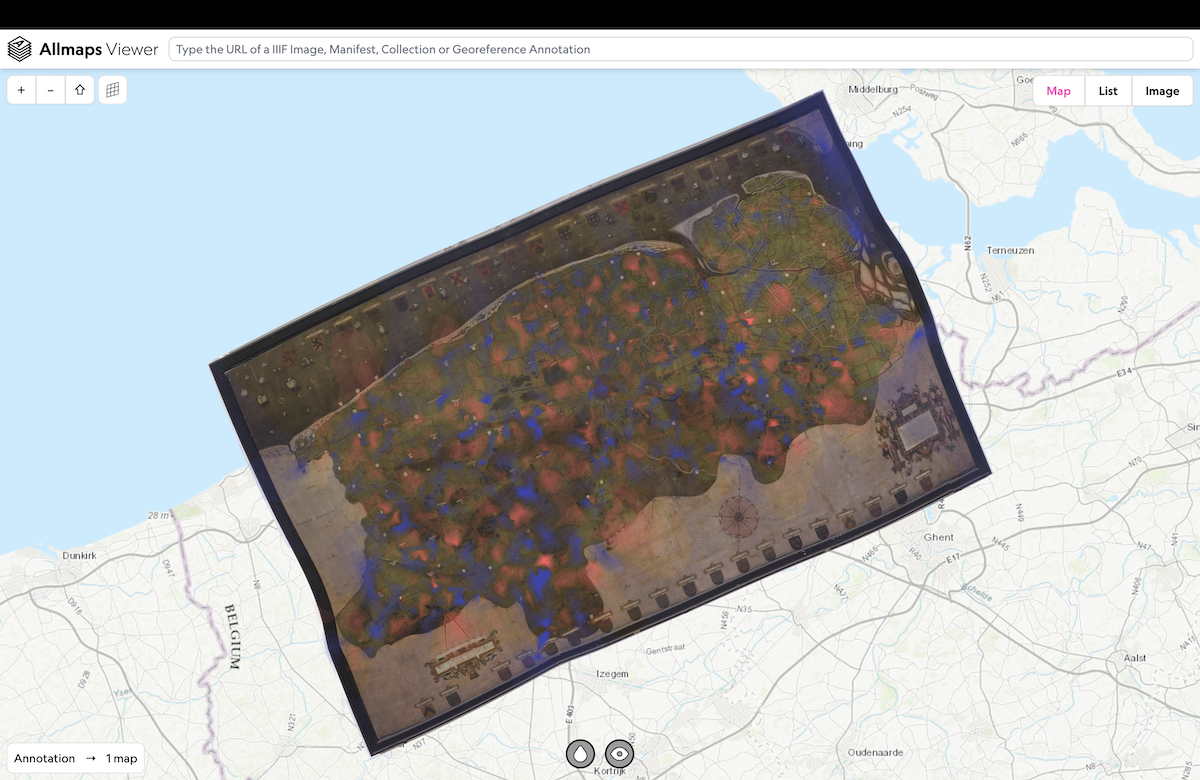

Initial inspection using the Allmaps Viewer revealed a few major and many minor inconsistencies, warranting further review and curation. This first inspection was notably facilitated by built-in features of Allmaps Viewer like opacity control and background color removal, allowing evaluating the alignment of the georeferenced historical image with the modern base map. Next, more advanced built-in features like distortion analysis quickly pointed to the major errors and enabled a visual comparison of the georeferencing accuracy between individual tiles and broader geographic areas.

While these tools are helpful for assessing volunteer-contributed georeferencing accuracy, they also offer valuable insights for future historical analysis of the map's overall accuracy. Researchers must always consider that discrepancies between the historical and contemporary landscape may arise not only from human interpretative errors during georeferencing, but also from historical causes: limitations in sixteenth-century measurement techniques, deliberate exaggerations or omissions by the cartographer, physical distortion of the medium over time, or natural landscape changes.

Thus, post-processing involved more than simply filtering errors. It required a careful distinction between genuine inaccuracies and historically meaningful deviations. An export of the resulting ground control points was thus created to allow the organizing team to review and refine the GCP dataset in ArcGIS Pro. This included correcting evident misplacements, as explained above, and improving geographic balance across the entire map region, by adding supplementary points where needed.

The final result is a curated, well-distributed set of 2,002 validated reference points, spanning the full extent of the historical map.

Now, you can explore the georeferenced Claeissens map in Allmaps Viewer:

Contributing to Community Cartography

Across the globe, mapathons have become a defining, though still relatively under-recognized, format within the growing field of community cartography. These events bring together volunteers to collaboratively map a specific area, often contributing local knowledge to improve or expand spatial data. From urban planning projects to humanitarian mapping through platforms like OpenStreetMap, mapathons demonstrate how cartography can function not only as a technical tool, but as a civic practice and a social experience. By combining open-source tools, shared spatial goals, and diverse forms of expertise, they turn mapping into a participatory act of collective engagement with place.

While community cartography has thrived in present-day contexts, its application to historical maps remains less explored. A few pioneering projects, such as the Early Modern Mapathons (George Mason and Virginia Tech, USA) and DigHimapper (University of Antwerp, Belgium), have introduced volunteers to historical GIS and Allmaps, enabling them to annotate or georeference early maps. However, in both examples, participants typically work individually and remotely, each contributing to separate map tasks.

Mapathon 1571 offers a distinct and complementary model. Rather than distributing individual maps to dispersed contributors, we brought together volunteers to collectively georeference a single large historical map; tile by tile, side by side, in a shared physical space. In doing so, we expanded the notion of community cartography into the realm of historical landscape interpretation, combining archival and topographical knowledge, open-source tools, and public engagement.

Our aim was not contemporary planning or humanitarian response, but rather to analyze, preserve, and spatially contextualize the past; while retaining the social and participatory strengths of the traditional mapathon format. Mapathon 1571 shows that historical cartography, too, can serve as a platform for collaboration and engagement.

As more archives and heritage agencies digitize their collections, this model holds great promise. It demonstrates how community-engaged mapathons can unlock historical landscapes, not only for academic research, but for broader communities of interest. In this sense, Mapathon 1571 does more than georeference a sixteenth-century map; it charts a path toward a more inclusive, connected, and place-based understanding of the past.

Jan Trachet is a postdoctoral researcher at Ghent University (Belgium) specializing in landscape archaeology and the history of cartography. His work explores early modern mapping practices and historical coastal landscapes, with a strong emphasis on integrating public outreach and participation into academic research.

Notes

1. Mapathon 1571 grew out of two interrelated projects.: first, Mapping/Painting the Medieval Landscape, a landscape-archaeological investigation of an intriguing 16th century map of the area around Bruges; and second, BLUE BALANCE: Sustainable Economic Development of the Flemish Coastal Areas for All, a project aimed at fostering inclusive, place-based engagement in the coastal transition to sustainability.

2. Huizinga, J., & Krul, W. Evert. (1995). De taak der cultuurgeschiedenis. Groningen: Historische uitgeverij.

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.