In 2024, we worked with the Massachusetts Historical Society (MHS) to bring a digital copy of Samuel Chester Clough’s atlas of Boston neighborhoods in 1798 into our digital collections.

At the Leventhal Center, we've had a long interest in this atlas. It was created around 1900, and reflects Clough's research into the spatialization of property ownership in Boston at the time just after the American Revolution. Because of the detail that Clough included, this makes the atlas a perfect candidate Atlascope, our tool for exploring historical urban geography at the scale of buildings and lots. With the Clough atlas now available in Atlascope, you can flip backwards in time all the way to the eighteenth century.

Since this is a pretty big update, we wanted to provide some context explaining the history of the atlas, where it comes from, and how you can most effectively use it to make sense of Boston in the late 1700s.

Samuel Chester Clough's atlas of Boston in 1798, now visible in Atlascope

A unique research document

Atlascope almost exclusively depicts urban atlases that were made for one of two purposes: fire insurance or tax assessment. The vast majority of these atlases were produced during the period between 1860 and 1940. Whether in the hands of insurance companies or municipal agencies, these atlases were important working documents, and they include detail right down to property lines and building materials.

Block 1000 from Clough's 1798 atlas

Although Clough's atlas visually resembles the fire insurance and tax atlases currently in Atlascope, it was not created for either of these purposes. Trained as a cartographer and surveyor, Clough compiled this atlas as part of his scholarly research towards a topographical history of Boston.

Working in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, over a hundred years after the time period he was mapping, Clough compiled information in the map from a wide range of sources including property information from the registry of deeds, John Winthrop's journal, and William Aspinwall's notes and city surveys. While his manuscript was never completed, Clough's maps offer a unique glimpse into Boston's neighborhoods in 1798—not through the eyes of an underwriter, city planner, or tax assessor, but through the eyes of a historian.

A historian's perspective

George C. Lamb's "Old Boston," a detailed map showing property ownership and buildings Boston as of 1640.

Clough drew inspiration for this historical cartography, at least in part, from George C. Lamb's reconstruction of the possessions in "Old Boston." This ten-sheet volume mapped property ownership across the city as of 1640. During one meeting of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts in which Clough was active, he noted that the existence of Lamb's map "acted as an incentive more powerful than any prize which might have been offered."

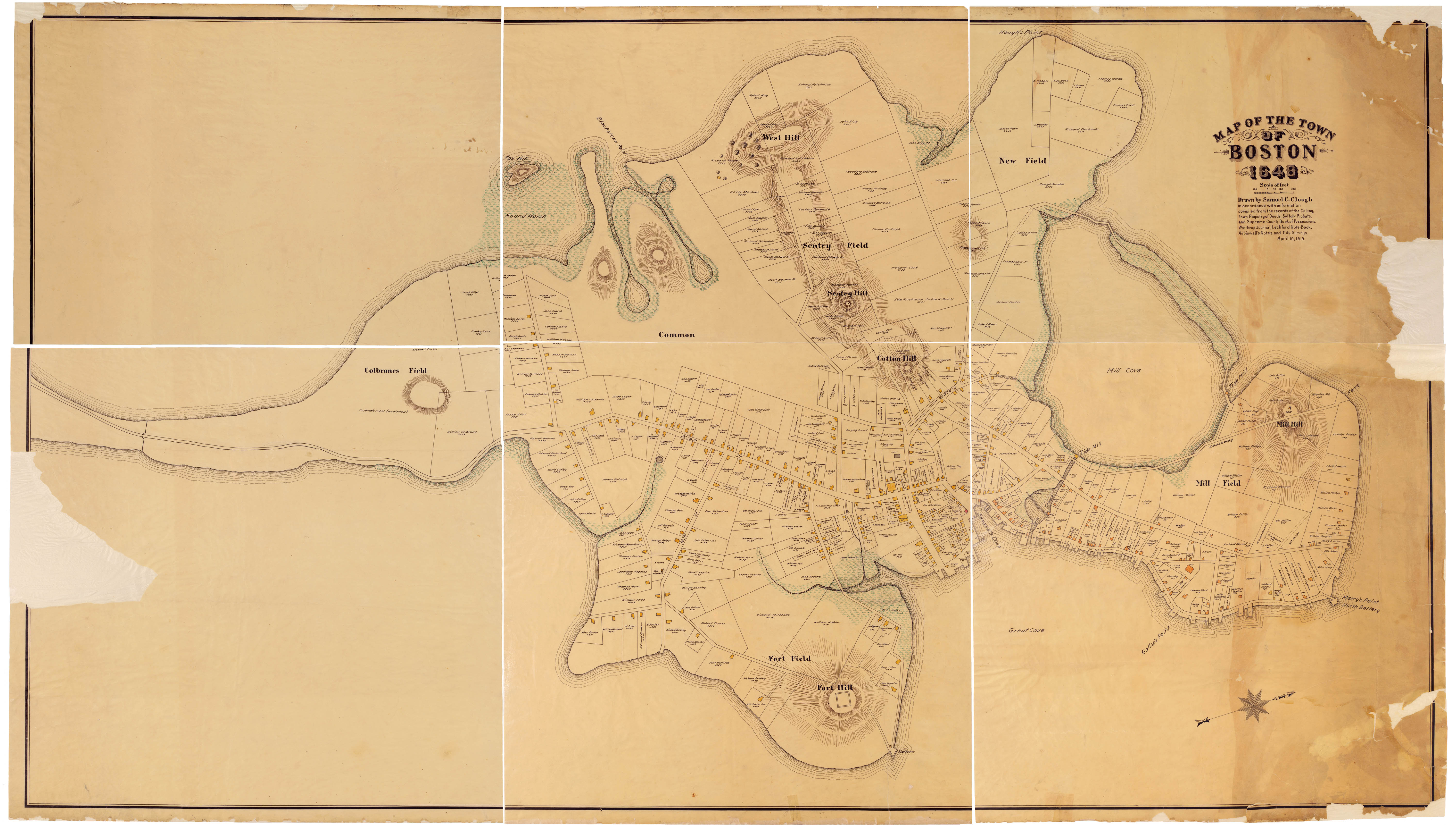

Certainly, Clough was also inspired by the vibrant industry of fire insurance and tax assessment maps that would have been contemporary to him. His "Map of the town of Boston in 1648," for example, employs cartographic conventions that are very familiar to Atlascope: yellow buildings for wood, pink for brick, X's for stables, and hachure lines for elevation.

Clough's map of Boston in 1648, which bears a striking aesthetic resemblance to fire insurance and tax assessment maps (from the Massachusetts Historical Society)

Unlike some of Clough's other maps, the 60-plate 1798 atlas doesn't depict individual buildings or structures. This means it looks a bit more homogenous than the colorful Bromley maps of Boston's South End or Walker maps of Provincetown in Atlascope. Clough's 1798 atlas also contains less text than highly descriptive Sanborn maps—but that certainly doesn't mean the information is any less meaningful.

Even at the time he was producing these maps, Clough understood them as documents that would be used by other researchers later on. His maps remain as useful in 2025 as they were in 1925, serving as a point of reference for projects like Katy Lasdow's study of women property owners in colonial Boston or the Birth of Boston project's work analyzing the Clough maps alongside Annie Haven Thwing's index of Boston residents from 1630-1882. Perhaps most importantly, the Clough atlas clarifies that a "J. Bois" once resided at the corner of Cross and Back Streets, which means that it can be definitively said, as a matter of historical fact, that Boston in 1798 was home to "The Back Street Bois." The land formerly owned by The Back Street Bois has undergone numerous transformations, and today occupies a stop on the Freedom Trail in the Rose Kennedy Greenway.

The Back Street Bois

What's left off the Atlascope layer

We hope that adding the Clough's maps of Boston in 1798 to Atlascope will make it easier to conduct historical research, both playful and serious. However, fully appreciating Clough's atlas requires acknowledging that some things are omitted from the composited Atlascope layer.

First, when we turn a digitized map into an Atlascope layer, we trim out lots of non-cartographic details. Some of those details are still important, even if they don't get captured in the final, stitched-together map layer. For instance, Clough created a block system that gave each piece of property a number that would remain consistent throughout the project. As you pan through the Clough layer, you'll notice numbers inside the parcels ranging from 1 to 99. These numbers correspond with a larger number between 100 and 5600. Taken together, they create a full index of each lot in Boston in 1798. The larger numbers don't appear in the Atlascope layer, but they are visible in the original plates, along with some names of property owners that are listed in the margins.

A note from Clough regarding landmaking and the history of the Mill Pond in block 1400

On some atlas plates, Clough also leaves a note explaining that "blue lines show 1798" while "black lines show former property lines." Without diving into Clough's papers at MHS, it's hard to know exactly what time period he means by "former," but it refers to sometime before 1798. Intersections of black and blue lines are particularly visible in places like Lynn Street (now Commercial Street) in the North End.

Finally, some pages of Clough's atlas also contain text that elaborates on features we see in the map. For instance, block 1400 contains a "First Baptist Church" surrounded by dashed lines, as well as the edge of Boston's Mill Pond. In a note that we clipped from the final Atlascope layer, Clough provides a useful history of made land in Beacon Hill, explaining how some buildings—including that First Baptist Church—were moved to account for the filling of Mill Pond. Clough uses his block numbering system to explain this history with regard to specific plots of land.

In short, while the Atlascope layer makes it much easier to explore Clough's atlas, it shouldn't be treated as the canonical source for map data—and that's actually true of all layers that we've published in Atlascope. For deep research, it's best to return to the original digitized atlases and study the cartographic features in their original context.

"Conflagrations are to be deplored"

With Atlascope, we've tried to build a tool that makes it fun and easy to place yourself in historical geography. When you use the tool, you are taking advantage of old maps in a way beyond their original intention. Today, we don't necessarily need these maps for insurance underwriting or tax assessment—instead, they become a portal to the past, and we can use them to teach and learn about topics like why leather factories congregated in Lynn, what cities looked like before urban renewal, and much more.

Even in the early twentieth century, Clough understood that these maps would gain a second life for future researchers, no doubt thanks to his sensibilities as a historian and cartographer who depended on old maps for his work. In 1913 remarks at the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Clough reflected on the simultaneously destructive and creative role of urban fires:

Such events as conflagrations are to be deplored, and they excite our sympathies for the personal losses of our early townspeople, and our regret that so much original manuscript material of historical value became a prey to the flames. Yet such catastrophes inevitably bring many changes, and the knowledge derived from the records of these changes is invaluable to the student of history, biography, and topography. Fire insurance in the early days was unknown, hence, in many cases, the property owners in a burnt district were nearly if not quite ruined, and compelled either to mortgage their realty in order to rebuild, or to sell their estates outright. The subsequent records therefore furnish important descriptive matter concerning that particular period. Much information can also be gleaned from those records relating to the changes in the street lines.

In a very real sense, Clough was ahead of his time in his estimation of fire insurance maps. As you explore the maps he made that are newly featured in Atlascope, you might also step into his shoes and consider his words as a parting prompt.

What information can you glean from those changes in the street lines?

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.