This digital publication was supported by the Leventhal Map & Education Center's Small Grants for Early Career Digital Publications program.

Power in industrial Boston

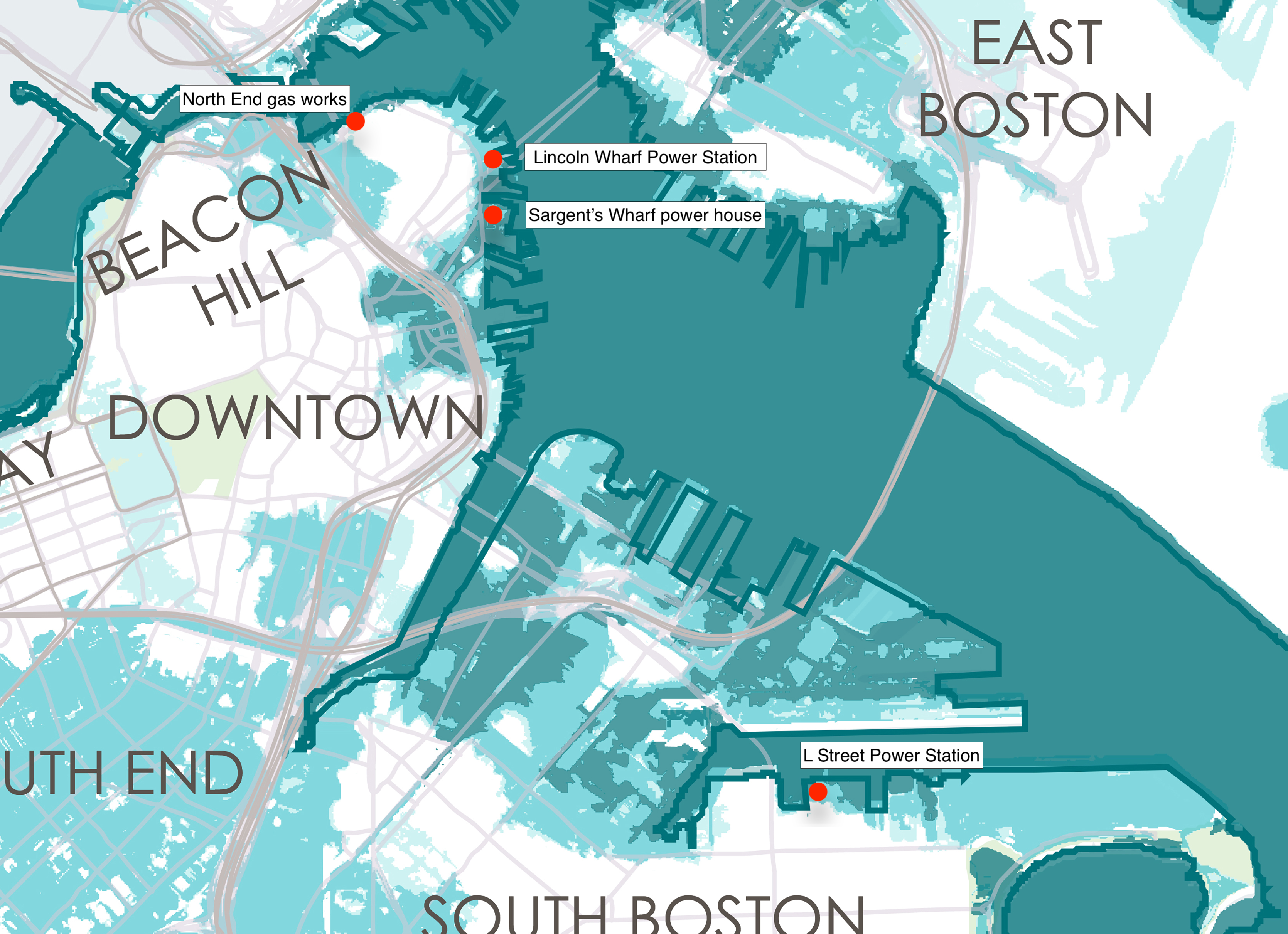

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, power stations were fixtures of Boston's landscape. Corporations burned coal to produce gas for lighting, including at the Boston Gas Light Company's works in the North End. Companies later generated electricity as a utility, at facilities like the Edison Electric Illuminating Company's L Street Power Station in South Boston. In addition, corporations often built their own power stations, such as the Quincy Market Cold Storage & Warehousing Company's power house on Sargent Wharf, and the Boston Elevated Railway Company's power station on Lincoln Wharf. While each complex met the company's distinct demands, Boston's power stations had a lot in common—especially their waterfront locations.

Maps demonstrate how energy production transformed Boston's waterfront. Because waterfront property owners were legally permitted to fill land and expand their site to the boundary of low tide (a process called landmaking), corporations saw waterfront sites as particularly well-suited for power generation.1 Industrial interests expanded the malleable waterfront to import and store large shipments of coal from steamships, which was especially desirable as shipping coal through railroads became increasingly expensive. Enterprises also generated power on waterfront sites because steam engines needed a supply of cold water to cool equipment and support the station's overall performance. Because inland parcels failed to provide similar benefits, corporations were eager to invest in waterfront land for energy production. For these reasons, the history of energy production offers a particularly good case study for how corporations reshaped the waterfront to make it more useful and valuable.

Maps also contextualize the ongoing efforts to adapt these sites today for new uses and values. The history of energy production left behind footprints, and developers contend with these footprints as they fill sites with a pastiche of new structures, labor over which buildings to reuse or remove, and fight with other stakeholders about land use along contested logistics corridors. Despite the challenges, developers have reinvested and reasserted that the waterfront is valuable. However, the sites are particularly susceptible to sea level rise—in part because energy-generating corporations previously filled the waterfront at low grades to expeditiously meet commercial demands. Amidst redevelopment approaches and impending inundation, the history of energy production helps us better understand the current strategies and the contemporary challenges for planning Boston's waterfront today.

The Boston Gas Light Company's Works

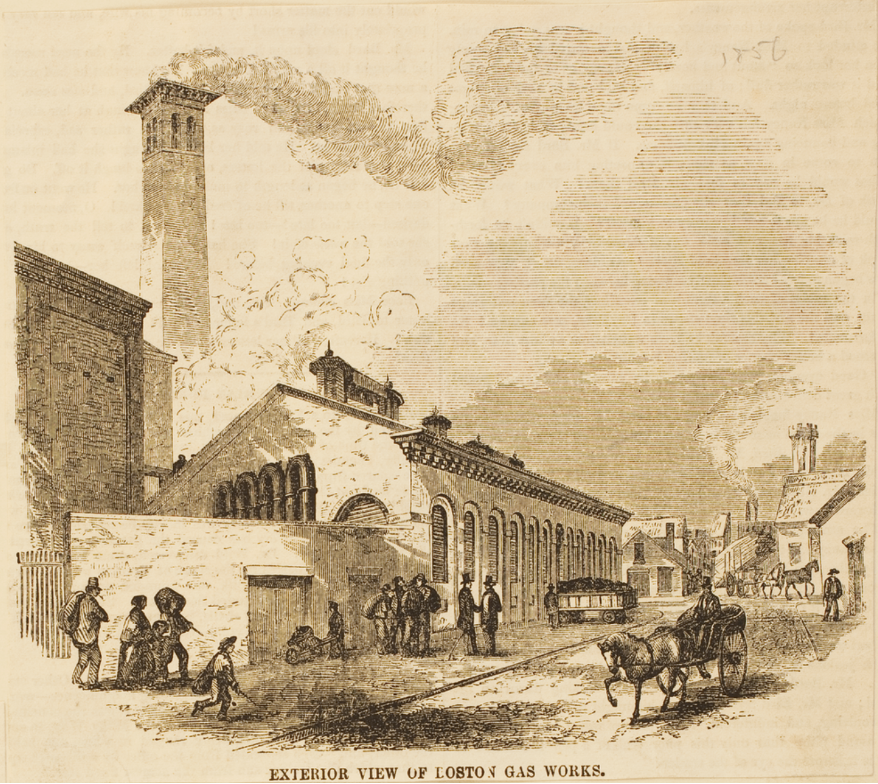

The Boston Gas Light Company transformed about 7.5 acres of the North End into a space for energy production. Several businessmen incorporated the Boston Gas Light Company in 1822. In order to maximize proximity to many customers, the company selected the North End for their gas production site, which was also called a "works." In 1828, the Boston Gas Light Company purchased a parcel of land in the North End between Commercial Street, Snow Hill Street, Hull Street, and Prince Street for their gas works.2 By the 1850s, the Boston Gas Light Company built a wharf and coal sheds on the waterfront. Because the company stored their coal in close proximity to their works on the wharf, the waterfront location allowed the company to control their fuel supply and subsequently bolster productivity.

Exterior view of Boston Gas Works and Interior view of Boston Gas Works (1856). Historic New England.

The works also encroached within 50 feet of adjacent dwellings in the North End. In the 1890s, residents fretted to their local representatives about the close proximity to the works, particularly due to "the amount of dark or thick gray smoke issuing from the chimney of the Boston Gas Light Company."3 Residents also reported struggles to breathe due to the gas works' emissions, and 22 deaths from asphyxiation were attributed to the increasing pollution.4

After the Molasses Flood in 1919, where a 2.3 million gallon tank of industrial molasses in the North End exploded and killed 21 people and injured 150 others, residents issued more formal complaints to municipal officials that the North End gasometer (gas holder) could similarly explode and harm the residents.5 Through transforming and expanding their land for gas production, the North End gas works also transcended property boundaries and infringed on residents' domestic comfort and wellbeing. Despite this, an investigation by city officials in 1920 determined that the gas works adhered to municipal building codes and kept the gasometer in place. As shown in the Atlascope view below, gas "factory" buildings segmented the parcel of land south of Commercial Street for gas production, while the nearby wharf housed a series of coal sheds.

This history of energy production continued to impact the North End's built environment, even after the gas company left the neighborhood. The gas company scaled back their production in the early twentieth century and gradually sold portions of the North End site. By 1903, railroad corporations purchased the waterfront property. The North Terminal Corporation acquired a portion of the site and constructed a garage by 1925. Finally, in the 1930s the City of Boston purchased the rest of the site and built a playground.6 After the railroad corporations abandoned the waterfront, the city's postwar urban renewal plans then reconfigured the waterfront for recreation. Despite the new land uses, the park, garage, and waterfront still remain exceptions to the dense parcels of brick dwellings in the North End, clearly visible in satellite imagery on Atlascope. The spacious parcels and large structures serve as reminders that the gas works once consumed and carved out the landscape for gas production.

The Edison Electric Illuminating Company's L Street Power Station

By the late nineteenth century, new corporations began to sell a different mode of lighting to customers. The Edison Electric Illuminating Company (EEIC) acquired the L Street Power Station in South Boston by 1902. Soon, the L Street Power Station became the EEIC's largest power plant in New England, and consumed about 90,000 tons of coal per year.7

"Expansion of the Boston Edison System," Electrical World and Engineer (May 1904)

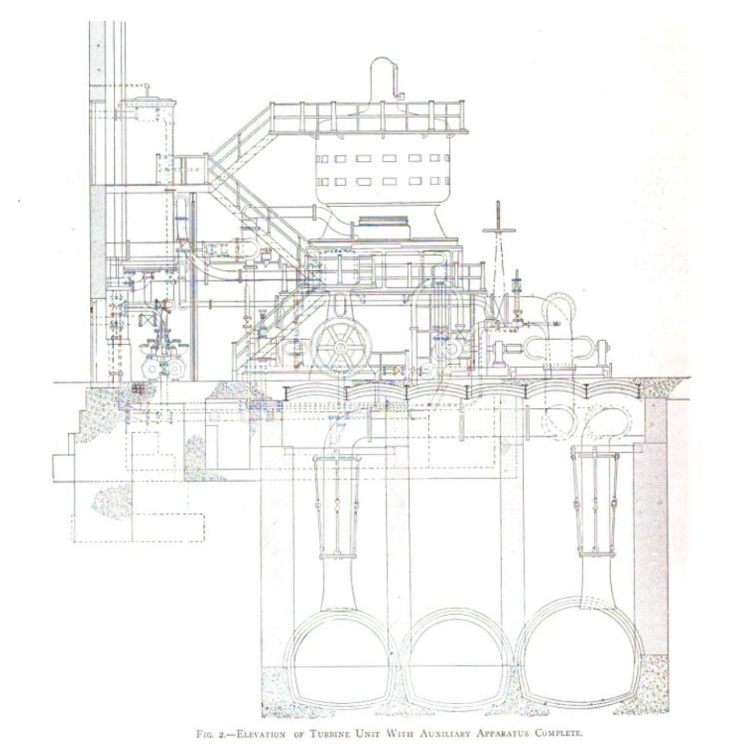

Coal arrived via a significant waterway between the outer harbor and South Boston—called the Reserved Channel—on which the power station was located. The L Street Power Station produced power efficiently because the EEIC built conduits into the waterfront, including pipes that pumped cold seawater into the station, cycled the cold water to cool the equipment, and then expelled the warmed water back into the channel. The conduits, depicted in the figure here, polluted the channel.

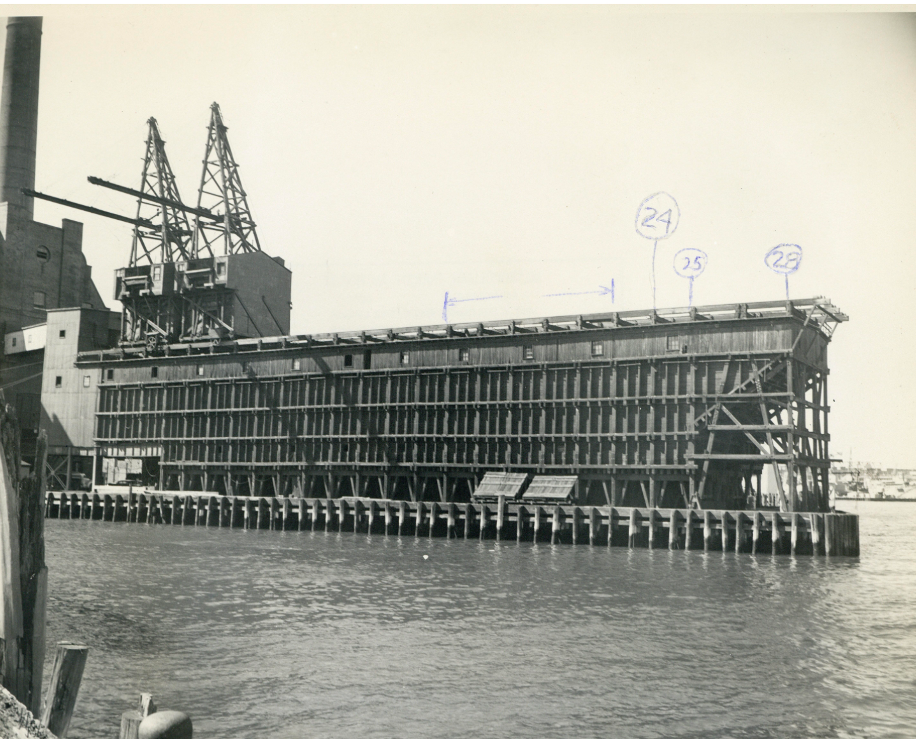

The EEIC dredged and remade the Reserved Channel for this infrastructure, and additionally expanded their waterfront site from 22.3 acres to 33.5 acres by driving piles into the harbor.8 On their new waterfront land, the EEIC primarily built coal towers, a movable crane, and conveyor equipment that transferred shipments of coal into the station by 1919. In Atlascope, comparing the 1899 atlas to the 1919 atlas highlights how the EEIC transformed the waterfront by making new land on the Reserved Channel and expanding the number of buildings within the L Street Power Station complex.

The L Street Power Station operated into the twenty-first century, but recent plans for the site's future demonstrate how property owners continue to struggle to reconfigure the waterfront. After the station's closure in 2015, developers planned a mixed-use complex for offices, commercial spaces, parks, and apartments.9 The plans focused on the adaptive reuse of the turbine building and the construction of new buildings on the rest of the site.

The planned redevelopment of the L Street Power Station site proposes the adaptive reuse of the power station’s turbine room, and also involves the construction of new buildings and the creation of waterfront public space. (City of Boston Planning Department, "776 Summer Street - Phase 1")

However, the history of industry on the shipping channel meant that stakeholders enacted land use restrictions, including the Massachusetts Port Authority (Massport), which, due to its operations at the nearby Conley Shipping Terminal, previously prohibited housing on the Reserved Channel.10 In 2024, the developers paid Massport to remove the deed restrictions, allowing them to proceed with their plans for the L Street Power Station mixed-use complex.11 Nevertheless, the developers still must contend with the previous buildings and infrastructure, which necessitate significant clearance and rehabilitation before the site can be viable for postindustrial uses. Comparing the 2023 satellite imagery of the L Street Power Station to its 1919 geography in Atlascope reveals that some of the power station's facilities and infrastructure no longer remains on the site.

The Quincy Market Cold Storage & Warehousing Company's Sargent Wharf Complex

At the turn of the twentieth century, gas and electricity were primarily sold to customers for lighting. Some corporations invested in their own power stations to fuel their operations. For example, in the late nineteenth century, the Quincy Market Cold Storage & Warehousing Company (QMCS) built warehouses throughout the Boston area. Their complex on Sargent’s Wharf included several 11-story warehouses along Eastern Avenue. The Power House sat at the edge of the wharf, visible on the right-hand side of this image.

"Quincy Market Cold Storage and Warehouse Co. building” (ca. 1930–1963), Boston Public Library Arts Department

By the 1890s, the QMCS had built warehouses with engines that mechanically cooled air. Between 1896–1905, the QMCS built new cold storage warehouses on Sargent's Wharf in downtown Boston. The two-acre location permitted the QMCS to transfer freight from the railroads on Atlantic Avenue and ships on the harbor. The QMCS's warehouse complex on Sargent's Wharf included a power house, which generated cold air and electric light for the warehouse.12

Similar to the Boston Gas Light Company and the EEIC, the QMCS reconfigured the waterfront for coal infrastructure, especially the coal shed on the edge of the wharf. Proximity to the waterfront granted the QMCS significant control over their coal supply at a key location for cold storage in downtown Boston. In contrast to its neighbors, however, the QMCS focused less on expanding the size of their site into the waterfront, and instead replaced the other buildings and tenants on the rest of the wharf. To expand their power house in 1906, the QMCS replaced 65–67 Eastern Avenue, which was a four-story tenement that previously housed seven Italian immigrant families.13 Comparing 1895 and 1917 in Atlascope shows the transformation of Sargent's Wharf from a landscape with many tenants and property owners to a primarily industrial site.

After Boston's deindustrialization in the early twentieth century, the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) planned to remove or adapt older buildings, and encouraged real estate developers to invest in housing, parking garages, hotels, and museums on the waterfront.

"Downtown waterfront, Faneuil Hall urban renewal area Massachusetts R-77," Leventhal Map & Education Center

The QMCS abandoned their Sargent's Wharf complex in the 1960s, but the BRA ultimately struggled to envision the warehouse as an adapted commercial or residential space due to its large size and its visual obstruction of the harbor.14 According to the planners, the complex retained the legacy of industry, and could not be aligned with the new vision for a postindustrial waterfront. Instead, the BRA demolished the warehouse complex. Although the BRA attempted to attract real estate developers to build new housing facilities on the site after the demolition of the warehouse, Sargent's Wharf remains a parking lot to this day (as the Atlascope view highlights below).15 Similar to the L Street Power Station, the industrial past reshaped the wharf and challenged redevelopment plans.

The Boston Elevated Railway Company's Lincoln Wharf Power Station

Other corporations invested in power stations for transportation services. By 1901, the Boston Elevated Railway (BERy) built elevated structures for streetcar lines along Washington Street, the Charlestown Bridge, and Atlantic Avenue. At this time, the BERy invested in four power stations (two in downtown, one in East Cambridge, and one in Somerville) for the elevated system. The 2.5 acre Lincoln Wharf site was an ideal location for a power station due to its close proximity to the Atlantic Avenue elevated route.

A comparison of the 1898 atlas to the 1908 atlas highlights how the BERy transformed Lincoln Wharf, making land north of Union Wharf, constructing the brick power house near Commercial Street, and investing in coal pockets at the edge of Lincoln Wharf. Using methods that echoed the EEIC's expansion of the L Street Power Station (such as driving wooden piles into the harbor), the BERy significantly reshaped this waterfront space.16

Like most power stations in the period, the operations relied upon a steady and accessible supply of coal shipments, so the BERy built coal pockets to transfer coal into the station.17 In addition, the Lincoln Wharf Power Station used the harbor's cold seawater to cool the steam-powered equipment, similar to the process at the L Street Power Station. However, the harbor did not always supply seawater reliably—for example, in 1906, the Boston Daily Globe reported that a particularly low tide prevented the BERy from intaking seawater at all four of their power stations, which resulted in "crawling cars," and delayed service where "a great many people got disgusted while the elevated was wrestling with the difficulty and left the cars, preferring to walk."18

The Lincoln Wharf Power Station's history of energy production carved out landscapes and buildings that were later redeveloped for housing by the late twentieth century. The MBTA (the successor to the BERy) owned the Lincoln Wharf Power Station by the 1970s, at which time they determined that they no longer needed the power station. By 1979, the San Marco Corporation, a nonprofit arm of the Sacred Heart Church in the North End, acquired the property and planned to create a housing development with a quarter of the units offered at affordable rates.19

The Lincoln Wharf Power Station was adaptively reused for apartments, which remains the building's function to this day. Author's Photo, 2023.

The development corporation reused the Lincoln Wharf power station building for the new apartment complex, which opened by 1987. In addition, private developers built new housing complexes on the spaces originally used for the power station's infrastructure. By 1993, the Kenney Development Corporation completed the Burrough's Wharf project on the site of the coal pockets, which offers luxury condos to this day.20 The redevelopment of Lincoln Wharf relied upon aggregations of housing structures, which necessitated strategic and intentional planning to adapt the space formerly carved out and made for energy production.

Will the Made Land be Unmade?

Energy production works and stations reshaped Boston's waterfront in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The Boston Gas Light Company, the Edison Electric Illuminating Company, the Quincy Market Cold Storage & Warehousing Company, and the Boston Elevated Railway Company remade, expanded, and altered waterfront spaces to meet their operational needs. To generate profit and produce gas or electric power, the companies impacted and displaced residents, altered harbor geography, and produced long-term spatial impacts on land use.

Similar to each corporation in the past, contemporary developers also attempt to create value from these sites today. The history of the power works and stations particularly impact redevelopment. Industrialists once built power stations in close proximity to the harbor with layered and intricate infrastructure into and on the waterfront, and due this history, developers either filled the large spaces with a miscellany of structures (seen at the North End gas works and the Lincoln Wharf Power Station) or struggle to receive support and approval to entice new investments (exemplified by the L Street Power Station and Sargent's Wharf).

When they were constructed, the power works and stations exemplified how property owners adapted the waterfront as valuable and useful space, which is also the approach that contemporary developers employ to remake the waterfront today. However, forging ahead with new land uses and developments will not protect each site's value forever.

To meet commercial and industrial demands expeditiously, property owners made waterfront land at low grades. As the annotated map of Climate Ready Boston's flooding progression demonstrates, much of the city's made land, including the four waterfront sites, will flood by 2070. Like in the past, private development typically remains focused on making useful and valuable landscapes rather than preparing for inundation. If we stay on the current course, the question should be asked: will the made land eventually be unmade?

This 2015 map from the City of Boston's Climate Ready Boston initiative depicts a sea level rise scenario of 36 inches, which is likely by 2070. All four sites of energy production discussed in this article fall within the 36-inch inundation zone.

Genna Kane is a PhD Candidate in American Studies, and her dissertation is an interdisciplinary spatial history of Boston's waterfront since the early nineteenth century. She focuses on the environmental and architectural developments of the waterfront and the shoreline's recent configurations as a climate resilient space. Genna draws on professional experience in community engagement and cultural programming in the Boston area, which informs her research and writing on the city's past.

Notes

1. Since the seventeenth century, legal ordinances permitted property owners near waterfronts to build wharves to the boundary of low tide (which was approximately 1,650 feet from the mark of high tide). Massachusetts General Court, "Liberties Common" in Thomas G. Barnes, ed., The book of the general lawes and libertyes concerning the inhabitants of the Massachusets (Huntington Library, San Marino CA, 1975), 35. For further reading on the history of landmaking in Boston, see Nancy Seasholes, Gaining Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003).

2. J. L. Richards, "The Boston Consolidated Gas Company: Its Relation to the Public, Its Employees and Investors," The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 31 (May, 1908), 61.

3. "City Government," Boston Daily Advertiser, Volume 167, Issue 104, May 1, 1896.

4. City of Boston, "Inspector of Gas: Proceedings of the Common Council, February 11, 1897," in Reports of Proceedings of the City Council Of Boston for the Year, Commencing January 4, 1897, and ending January 1, 1898 (Boston: Municipal Printing Office, 1898), 177.

5. Earl H. Barber, "Report to the Board on the Location and Surroundings of Gas Holders in the City of Boston made with Reference to Chapter 23 of the Resolves of 1919," in Document No. 598, Special Report of the Board of Gas and Electric Light Commissioners, January, 1920 (Boston: Wright & Potter Printing Co., 1920), 22.

6. "Real Estate Transactions: North Terminal Corp Buys Large Area," Boston Daily Globe, 11 May 1925: A15.

7. "Operation of the Boston Edison Company's L Street Station," Electric World Vol LIII, No. 22 (May 1909), 1283.

8. Because the L Street Power Station produced about 60,000 cubic yards of ash and cinders, the EEIC primarily used the coal waste as the filling material for landmaking. Report of the Directors of the Port of Boston: Year Ending November 30, 1915 (Boston: Wright & Potter Printing Co, 1916), 62.

9. Tim Logan, "Southie power plant fetches big price," Boston Globe, 26 Apr 2016.

10. Tim Logan, "18-wheeler views?: L Street Power Station redevelopment to include $75m haul road for trucks," Boston Globe, 11 May 2017: B.11.

11. Jon Chesto, "Massport gets $12 million to allow housing near Conley Terminal haul road," Boston Globe, June 27, 2024.

12. "The New Quincy Market Cold Store," Cold Storage and Ice Trade Journal Vol 15 (August 1906), 29.

13. 1900 United States Federal Census, Massachusetts, Suffolk County, Boston, District 1232. Accessed through Ancestry.com.

14. Anthony Yudis, "Real Estate: Mixed emotions over Quincy Cold Storage An architect would salvage, not destroy ugly landmark," Boston Globe, 07 May 1972: B1.

15. John King, "Developing the Waterfront: Question: Should City and rural shore property be treated differently?" Boston Globe, September 26, 1989, 25.

16. "New Power Station and Elevated Railway System in Boston," The Street Railway Journal Vol XVII No. 9 (March 2, 1901), 254.

17. "Spark From Motor: It Caused a Slight Blaze on Top Floor of Lincoln Wharf Power House of the Elevated," Boston Daily Globe, 02 Mar 1907, 6.

18. "Tide Out, Tied Up: Last Evening's Delays Thus Explained. Low Water Made Trouble at Power Stations. Street Cars Crawled or Stood Still," Boston Daily Globe, 24 Apr 1906, 9.

19. "Church group hopes to recycle Lincoln Wharf," Boston Globe, 21 Jan 1979: 181.

20. Jennifer Kingston, "Northeast Notebook: Boston; Condos to Rise on Pier Site," New York Times, January 10, 1988.

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.