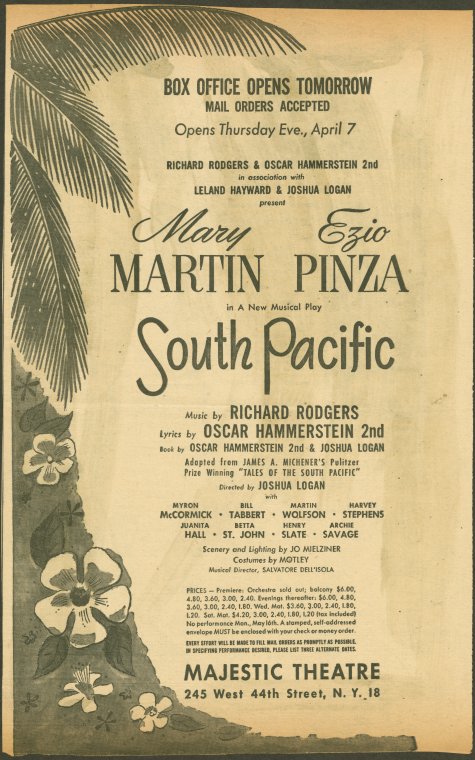

Detail from the printed program for the musical South Pacific, Courtesy of the New York Public Library digital collections.

On April 7, 1949, the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical South Pacific opened on Broadway and became an instant smash hit with a record-breaking five-year run. Songs like Some Enchanted Evening, Bali-Ha’i, There Is Nothin’ Like a Dame, and I’m Going to Wash That Man Right Outta My Hair were on everyone’s lips. On the anniversary of the musical’s opening 72 years later, Broadway is beginning to come back to life after a difficult pandemic year of shuttered theaters. But recent acts of racist violence against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders should also make us question how stereotypes of Asian ethnicities have been shaped by images of the “other” in popular culture for many decades.

Miguel Covarrubias, Peoples of the Pacific (Pacific House, 1940).

It’s illuminating to consider Rodgers and Hammerstein’s iconic piece of American culture in light of a pictorial map from around the same time created by renowned Mexican artist and ethnographer Miguel Covarrubias. A prodigious artistic and intellectual talent, Covarrubias became one of Vanity Fair’s premier caricaturists, and also designed sets and costumes for the theater. Covarrubias later taught ethnology at the Escuela Nacional de Antropología, and, as artistic director and director of administration for the Palacio de Bellas Artes, led the development of a new era in Mexican modern dance. In addition to his creative output and influence in contemporary arts, Covarrubias was known for his scholarly analysis of pre-Columbian art, as well as his ethnographic book Island of Bali, written after his extended honeymoon there.

Covarrubias was invited to create six oversized murals for the 1939–1940 Golden Gate International Exposition on San Francisco’s artificially built Treasure Island. The murals were later exhibited at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Five of them were displayed until 2001 at the World Trade Club in the Ferry Building under the auspices of the Port of San Francisco. One of the murals, The Fauna and Flora of the Pacific, can be seen today at the de Young Museum, but no one knows the whereabouts of the sixth mural, Art and Culture. The colorful murals were so popular that they were reproduced in 1940 as a printed portfolio titled Pageant of the Pacific. Two maps from the portfolio, titled “Peoples of the Pacific” and “Art Forms of the Pacific Area”—the latter a reproduction of the now-vanished Art and Culture mural—are in the Leventhal Map and Education Center collection.

Miguel Covarrubias, Art forms of the Pacific area (Pacific House, 1940).

The exposition theme “Pageant of the Pacific” was launched with remarks by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. “As the boundaries of human intercourse are widened by giant strides of trade and travel,” Roosevelt said, “it is of vital import that the bond of human understanding be maintained, enlarged and strengthened rapidly. Unity of the Pacific nations is America’s concern and responsibility.” Roosevelt cast the Pageant as an exercise in liberal American internationalism, hoping that it would “truly serve all nations in symbolizing their destinies, one with every other, through the ages to come.”

This insistence about the American role in protecting “all nations” came at a time that Europe was tearing itself apart in the first years of the Second World War. Although the bombing of Pearl Harbor had not yet drawn the United States into the war, the Japanese Empire was already expanding across the Pacific, including the brutally violent Japanese occupation of Manchuria. The United States was hardly a disinterested onlooker. The Philippines were part of the United States’ own Pacific empire at the time, and U.S. foreign policy was already moving to counter the expansion of Japanese power in the Pacific. The Pageant, therefore, represented one attempt to cast the United States as a friendly, culturally-tolerant protector of the Pacific’s many different ethnicities and nationalities.

All six of Covarrubias’s maps feature the same geography, with the Pacific Islands shown in a painterly swirl of ocean in the center, surrounded by the continents of Asia, Australia, and North and South America. Covarrubias brings together his ethnographic approach and his artistic hand to illustrate an anthropological view of cultural diversity. Dozens of human figures in traditional dress populate the all the continents and islands in Peoples of the Pacific, with colored zones defining the territories of the Micronesian, Melanesian, and Polynesian inhabitants. A few are humorous, such as the portly gentleman in New York smoking a cigar in a swivel desk chair labeled Easterner (detail shown), and the blonde swimsuit-clad woman representing a Californian.

Most of the figures, however, focus on non-white or indigenous peoples, such as a Sioux chieftain in the U.S. West, a Zapotec woman in southern Mexico balancing a basket on her head (detail shown), a Mongolian horseman, and a Cantonese woman with a child. The color-coded legend reflects the racial divisions commonly used by ethnographers at the time: Mongoloids, Causasoids and Negroids including Melanesians. In the area marked “Melanesian” we see darker brown figures labeled Papuan (woman with grass skirt detail shown), New Irelander, Trobriand I., Solomon I., Fijian, New Hebrides (detail shows man with spear), and New Caledonian. “Polynesians and Micronesians” are listed and color coded separately from the three major categories; their figures have lighter brown skins.

In the islands, men in loincloths holding spears, and bare-chested women predominate. We can ask ourselves to what extent did these earnest and careful depictions, especially taken together with Covarrubias’s Art Forms and his other map murals, expand appreciation for multiple cultures—and how much did they serve to titillate white visitors in San Francisco and New York and distance Americans from an exoticized “other?”

The question becomes much more pointed in considering the musical South Pacific. Rodgers and Hammerstein based the Broadway show on James Michener’s first book, Tales of the South Pacific, published in 1946, a collection of short stories based on his time serving as a lieutenant naval historian in 1940 and 1941 in the Solomon Islands. Many characters, places, and situations ended up in the musical: Bloody Mary, a Tonkinese woman who chews betel nuts and sells local artifacts to U.S. seamen; Ensign Nellie Forbush, a young, naïve Navy nurse from a small town in Arkansas; and Joe Cable, a Princeton-educated Marine lieutenant.

The plot of the musical revolves around two interracial/intercultural love stories during the U.S. occupation of the islands, told from Americans’ points of view. Nurse Nellie sings I’m in Love With A Wonderful Guy about a French colonial planter on the island, but recoils in horror from the relationship when she meets his children of a Polynesian mother. Lieutenant Joe, subjected to the manipulative matchmaking of Bloody Mary, uncontrollably lusts for and seduces her young beautiful daughter Liat, but hesitates to marry and bring her home where he fears she won’t be accepted in Pennsylvania.

The plot’s turning point is when Joe sings You’ve Got to Be Carefully Taught, preceded by his realization that racism is “not born in you! It happens after you’re born…” The song was controversial, but Rodgers and Hammerstein, known for their decades-long stances against racism, insisted it be kept in the show. When the musical toured to Georgia in 1953 during the early days of the “Red Scare,” legislators there introduced a bill outlawing entertainment with “an underlying philosophy inspired by Moscow,” with one lawmaker saying that a song justifying interracial marriage was implicitly a threat to the American way of life. The song became something of a civil rights anthem, has been covered by many singers, was the theme song for National Brotherhood Week in the 1950s, and was referenced in Hamilton in the song My Shot with the line, “I’m with you, but the situation is fraught. You’ve got to be carefully taught; if you talk, you’re gonna get shot!”

The mystical and mythical island Bali Ha’i, subject of the haunting song, plays a central role in the plot, as a place full of sensuous women offering themselves to visiting American sailors, ritual dances, and as Liat’s home, to which Joe Cable is inexorably drawn. Michener stated that he envisioned the place before naming a particular island as its reality, but in his Tales From the South Pacific he situates Bali Ha’i “within the protecting arm of Vanicoro,” in the Solomon Islands. However, it’s widely thought that the model was a mist-covered island then called Aoba, visible from Espiritu Santo, the site of a major World War II airbase in the New Hebrides. Today it is called Ambae Island in the nation of Vanuatu.

Much has been written about South Pacific, including its depiction of how Nellie’s final acceptance of marrying into an interracial family advanced the cultural politics of a post-war era. During this period of Cold War Orientalism, writer Pearl Buck and others advocated for Americans to adopt Asian children, the “Hiroshima maidens” were brought to the United States for plastic surgery for injuries suffered from the atomic bomb, and the Family of Man photographic exhibition curated by Edward Steichen celebrated the universal aspects of the human experience.

The white characters in South Pacific were musical theater cartoons, including the lonely seamen who sing There Is Nothin’ Like a Dame, one of whom clownishly ducks Navy rules, and the ditzy blonde girl from Little Rock who sings I’m Going to Wash That Man Right Outta My Hair. Nonetheless, many argue that South Pacific contributed to racist stereotypes of Asians that persist today, including the evil and manipulative dragon lady, and the submissive yet seductive young enchantress. Audiences in the 1940s would have been familiar not only with the immediate history of war against Japan, but also decades worth of embedded white supremacist ideas about the “Yellow Peril” that held Asians in a state of naturalized racial inferiority. Alarmingly, the portrait of Lieutenant Joe Cable as a dominant man who cannot control his carnal desires when tempted by an Asian woman is all too eerily resonant with the account of a man with a self-confessed sex addiction who shot six women of Asian descent in Atlanta in March 2021.

Considered together, Covarrubias’s maps of the Peoples of the South Pacific, and Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific musical reveal how people of Asia and the Pacific Islands were portrayed in U.S. popular culture during the 1940s. Both depictions, carefully crafted, attractive, and entertaining, were made with the best of intentions of furthering multi-cultural education and countering racism. In context, they both likely had a positive impact on blunting racism and fear of the “other” in their day. Yet in retrospect, they also serve as warnings to be vigilantly on guard and aware how even the most well-meant cultural products can become tropes that end up perpetuating corrosive stereotypes.

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.