This digital publication and map was supported by the Leventhal Map & Education Center’s Small Grants for Early Career Digital Publications program.

A Little Syria in Boston

Boston’s first Arabic-speaking community was made up of immigrants from Ottoman-controlled Greater Syria who began arriving in the late 1880s. By the early years of the twentieth century, the city was home to a thriving “Little Syria,” also called Syriantown and the Syrian Colony.

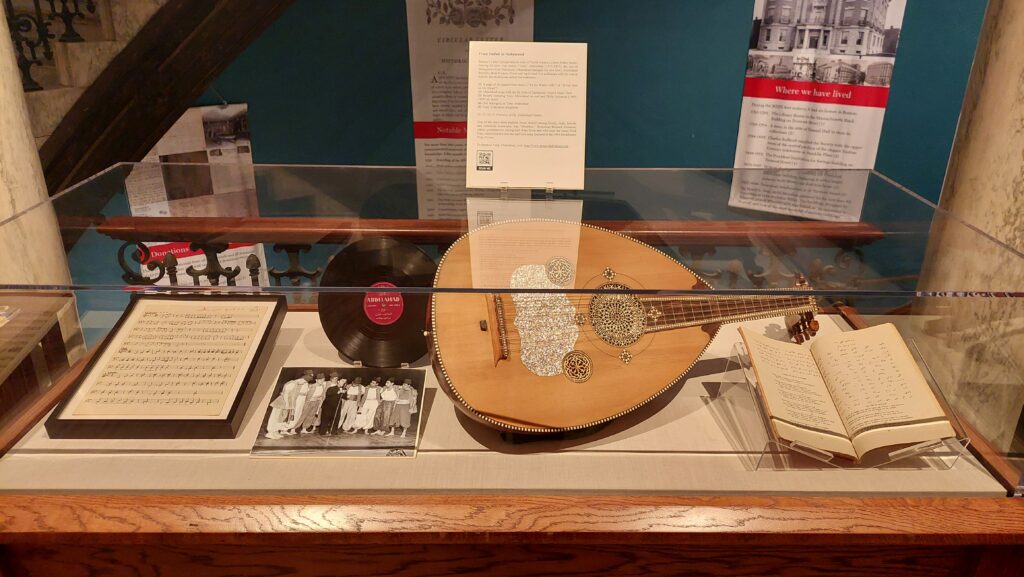

Photos from a 2023 exhibition at Massachusetts Historical Society on Boston’s Little Syria.

Today, few visible traces of this neighborhood remain. The Boston Little Syria Project has sought to document its history in collaboration with former residents and their descendants, demonstrating the longstanding presence of Americans of Arab origin in and around Boston and their contributions to communal life here.

The early community was clustered in crowded brick tenements around Oliver Place (now Ping On Alley) and Oxford Street. As it grew, social and commercial life came to center on Tyler and Hudson Streets in the South Cove, just south of the Chinatown Gate. “This square-mile colony … was exclusively Arab territory,” wrote resident Gladys Shibley Sadd (1908-2005) in her memoir, True Love Stories (2000). Here, “people prided themselves on their ability to function within the culture of mainstream American while clinging tenaciously to their own ethnic roots and traditions.”

In the 1920s and 1930s, the community spread south down Shawmut Avenue. By 1937, according to the Boston Globe, Boston was home to as many as 15,000 Syrians (whose families originated in what was soon to become an independent Lebanon as well as present-day Syria). Soon, however, the residents of Little Syria began emptying out—largely to West Roxbury and the Boston suburbs. The construction of the Massachusetts Turnpike in the 1950s and the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA)’s razing of urban blocks accelerated generational and socioeconomic shifts. Residents joined grassroots organizers in Chinatown and the adjacent multi-ethnic neighborhood of New York Streets to push back against demolition plans, but this era marked the decline of Little Syria.

Since its launch in May 2022, the Boston Little Syria Project has taken different forms to reach both local audiences and those in the broader Arab diaspora: walking tours, exhibitions, a bilingual publication, a podcast episode, and now a digital map.

A walking tour of Boston’s Little Syria.

Participants on the walking tour stroll south from the Chinatown Gate through the South Cove and down Shawmut Avenue to Peters Park, named for Sadie and George Peters (originally of Kfar Hilda in northern Lebanon). Passing a string of million-dollar townhouses, they eventually arrive at the shuttered Sahara Restaurant, which closed for business in 1972 but whose striking red, white, and yellow sign serves as a local landmark and the most visible reminder of the community that once congregated on this street. Walking the neighborhood gives a keen sense of the changes to the urban fabric that influenced Syrian immigrants' settlement in the area and eventually their departure from it. When crossing over the chasm of I-90, which splits the South Cove from the South End’s Shawmut corridor, participants often remark on experiencing a keen sense of disconnection.

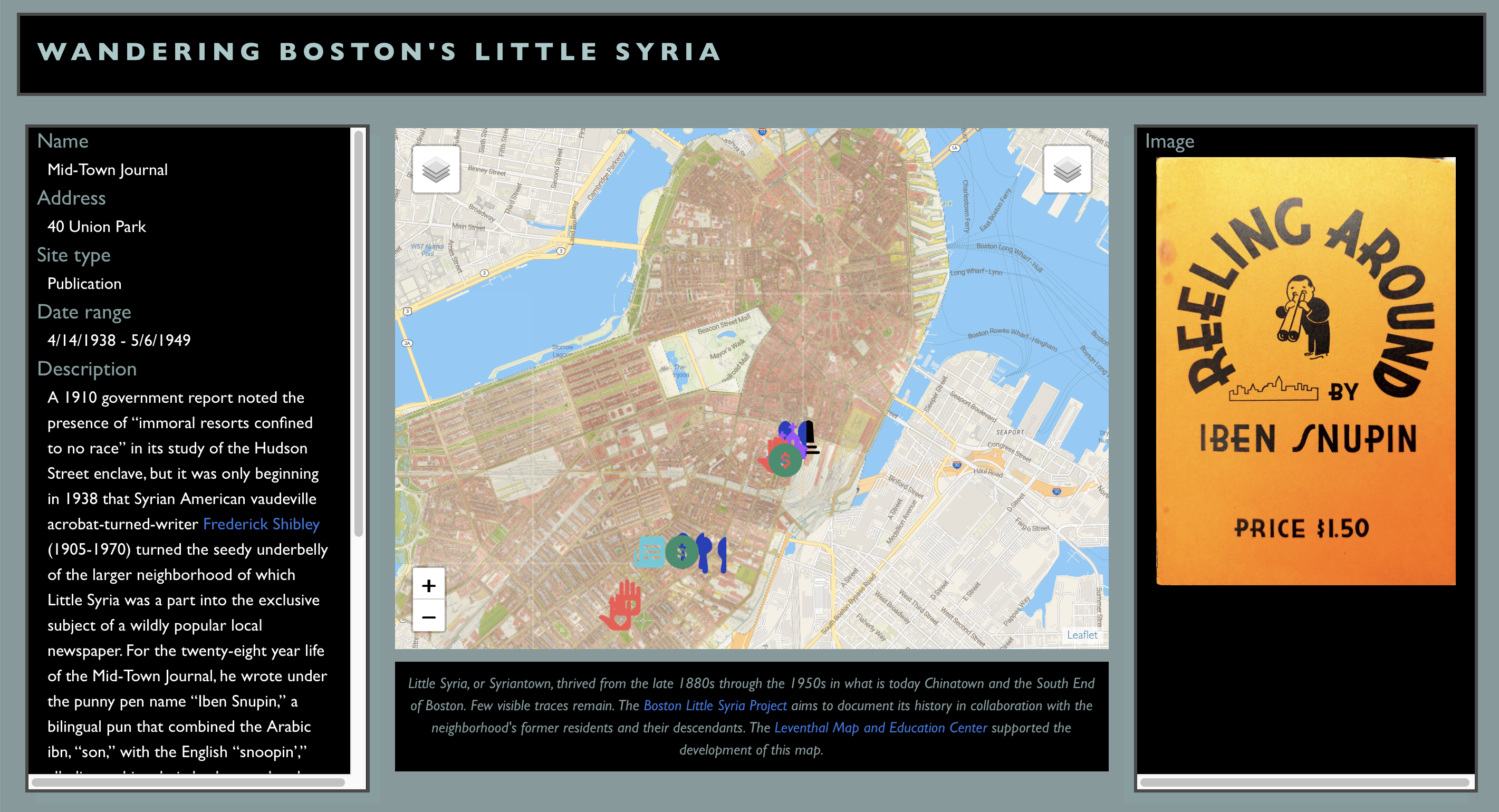

Wandering Little Syria with digital maps

Yet not all who are interested in the history of Boston’s Syrian quarter can join a live walking tour or view an exhibition. A digital map offers the possibility of keeping the history of the community rooted in the physical space of the neighborhood while encouraging people to explore on their own, in person or online.

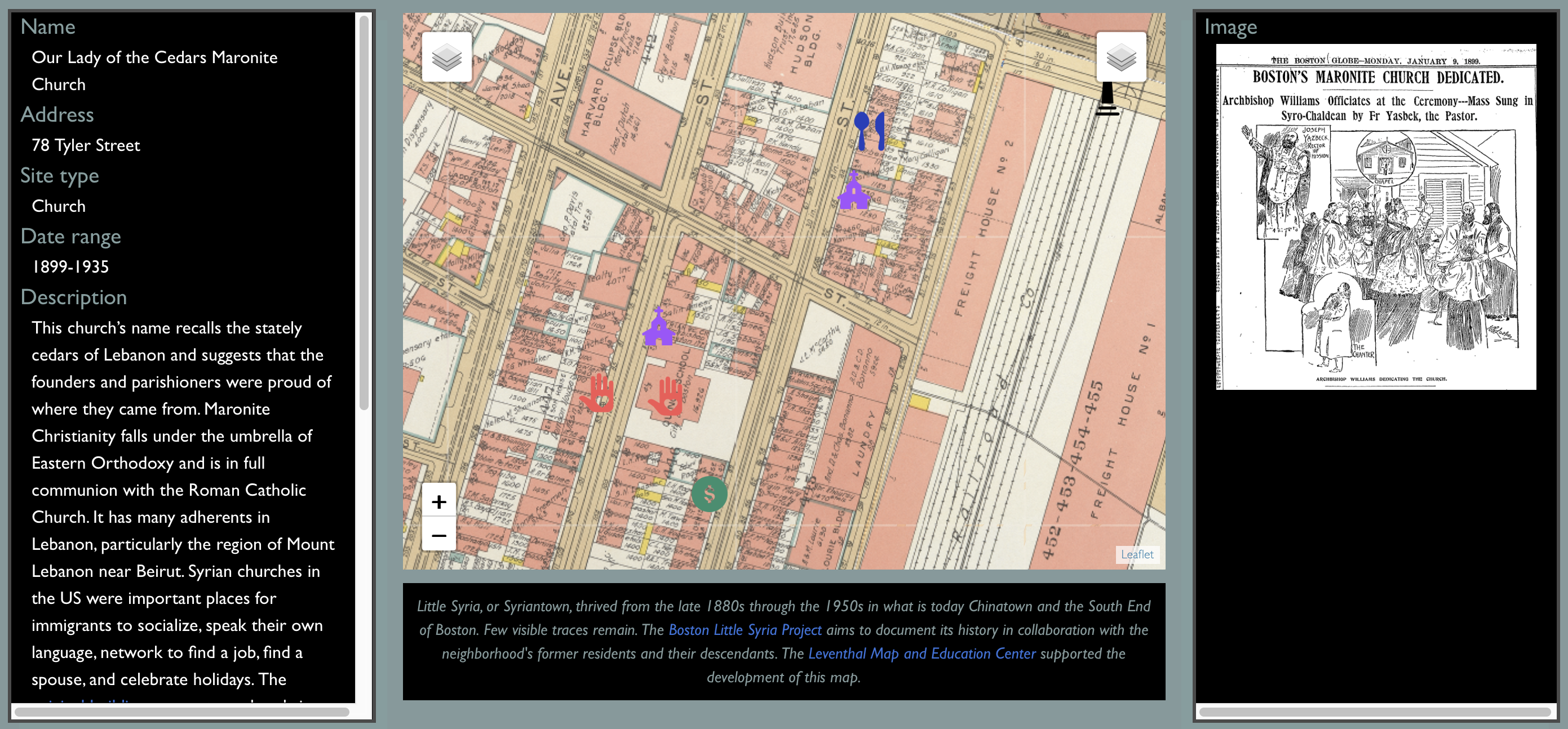

The Boston Little Syria map is built on several layers of G.W. Bromley and Co.’s Atlas of the City of Boston, a fire insurance and cadastral atlas that was already georeferenced and accessible through Atlascope. The final historical layer is composed of maps produced by the Boston Redevelopment Authority in the early 1960s, when the agency was identifying large swaths of the Syrian neighborhood as “blighted.” These layers were chosen because they illustrated the major stages of neighborhood transformation, from the emergence of an Arab presence to its near disappearance.

Most importantly, the digital map records traces of the lives lived in this neighborhood. One of earliest confirmed sites is the address on Oxford Street where Father George Maloof, a priest dispatched by the Syrian Orthodox bishop in New York City, set up a home chapel around 1900, effectively establishing the first church in this predominantly Christian community. Thirty years later, but just a few blocks away at 52 Hudson Street, was Deeb Salem’s Nile Restaurant, billed by its proprietor as “the best restaurant this side of the Pyramids.”

The area was dotted with dry goods shops, a sampling of which are visible on the map (A.N. Haddad’s, Moses Shibley’s, and Massis Grocery, for example). It was common—especially in the four-story brick buildings of the South Cove—to have a store on the first floor, supplies for pack peddlers in the basement, and living spaces upstairs. Some had specialty items like the latest Arabic records from Cairo, which were sold at the Armenian-run Arax Grocery on Kneeland Street in the early years of the twentieth century.

A cluster of Arab institutions along Tyler and Hudson Streets in 1938, including Our Lady of the Cedars Maronite Church, Maloof Records, and the Nile Restaurant. Explore the map to read more.

Civic organizations reinforced a sense of community life, and there were many. One is the Lebanese Syrian Ladies' Aid Association, represented on the map at 101 Tyler Street in the South Cove (1917-1929) and 44 West Newton Street in the South End (1929-1964). The Society, which was established in 1917 in the thick of the acute humanitarian crisis of World War I, is no longer at either address. However, it is still active, and its continued existence is but one reminder that while the original neighborhood is gone, some former residents—and many of their children and grandchildren—remain tied to the community.

Whether they are near or far, the Boston Little Syria Project aims to gather and connect their recollections, photographs, and archives, reweaving them into the urban landscape. It adds an often-neglected layer to the texture of Boston history—one that is shared by Arab Americans and non-Arabs alike who have made the city their home.

Chloe Bordewich is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Toronto’s Jackman Humanities Institute. She received a PhD in history and Middle Eastern studies from Harvard University in 2022. From 2022-2023, she held a postdoctoral fellowship in public history at Boston University and the U.S. National Archives. Her research focuses on empire, media technologies, and public access to knowledge.

Lydia Harrington is a historian and curator specializing in Middle Eastern architecture and migration from the Middle East to the US. She earned her PhD from Boston University’s History of Art and Architecture Department in 2022 and was a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture at MIT in 2022-2023. She was previously Senior Curator of the Syria Museum.

As co-leaders of the Boston Little Syria Project, Harrington and Bordewich have led neighborhood walking tours and public events. They have curated exhibitions at MIT’s Rotch Library (December 2022-March 2023), the Massachusetts Historical Society (April 2023), and the University of Massachusetts Boston’s Healey Library (January-May 2024).

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.