Teaching Boston: Resistance to Slavery

This new BPS Humanities newsletter feature is designed to demonstrate to students how history happened here in Boston. All of these primary sources come from Boston institutions within a mile of each other: the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Massachusetts Historical Society, and the Norman B. Leventhal Map and Education Center at the Boston Public Library.

We have selected six primary sources that can be used in many contexts, and specifically apply to the transition from MA Units 4 → 5 or IH Units 3 → 4. For each source, you’ll find background information, guiding questions, and ideas for classroom discussion.

These primary sources highlight how people in the nineteenth century—free and enslaved, famous and ordinary—shaped debates about slavery, freedom, resistance, and representation. Each source reveals a different strategy for surviving, documenting, or resisting a world built on enslavement.

Each primary source encourages students to ask: Who is resisting the law, and how?

Plus, we’ve included flexible activities so you can mix and match objects to fit your teaching goals.

Focus Objects

Dave (later recorded as David Drake), Storage Jar, 1857

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Quick Info

Many enslaved people were skilled potters who were forced to use their talents to create food storage jars and other goods. What makes the artist of this jar, Dave (later recorded as David Drake) stand out is not only his talent for shaping clay, but that he signed and even wrote short poems on his work. His choice to show his ability to read and write is significant because of the laws throughout the south that prevented enslaved people from being taught to read. As an enslaved potter, Drake was not permitted to possess the jars and did not receive remuneration (payment) for them or exercise any control over their fate.

Before the late 1700s, when slavery was legally forbidden in Massachusetts, there were enslaved potters in Boston as well. For example, Jack and Acton were two potters forced to create various wares nearby in Charlestown (near what is now City Square Park).

Guiding Questions

Where does Dave place the writing? Why does the visibility of his name matter?

What risks and what forms of power can come with telling your own story/making yourself visible?

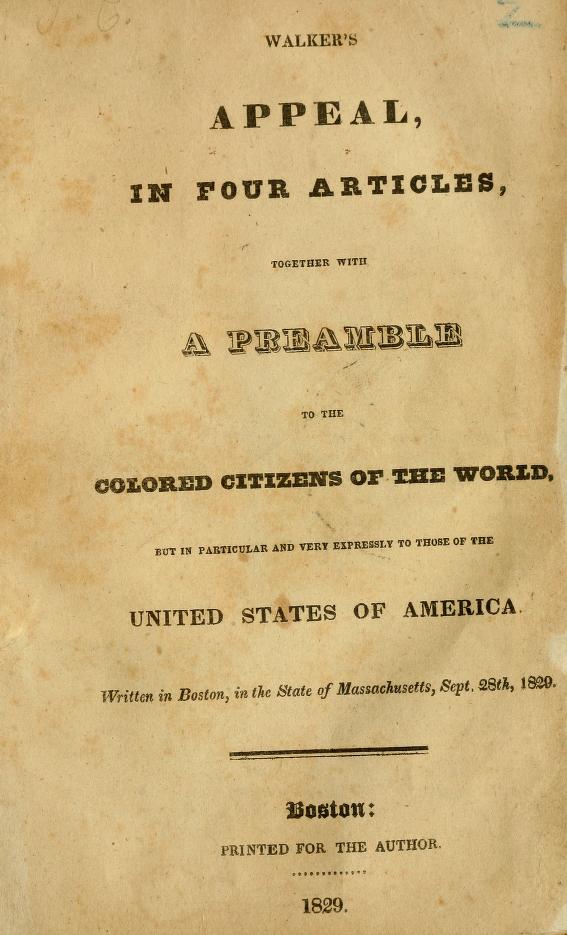

Walker's Appeal … to the Colored Citizens of the World

Boston Public Library

Quick Info

In 1829, Black Bostonian David Walker self-published an incendiary pamphlet that repurposed the Declaration of Independence for the antislavery cause. It was considered so dangerous in its time that it inspired new Southern laws banning the teaching of enslaved people to read and write. In many states, the text was considered so dangerous by white lawmakers that possession of Walker’s Appeal was punishable by death. Walker asked sailors to sneak it into ports they visited and even sewed it into clothing to hide it from the law.

Southern authorities, afraid of its message, destroyed many copies. The copy in BPL Special Collections is one of nine known to survive in the United States.

Walker’s text contained radical calls to action, which was unusual to see from a Black author in print at the time. He urged both free and enslaved Black audiences to rise up against racist oppression across the country.

Guiding Questions

Who would have been afraid of Walker's message? Who would have found hope in it?

If you needed to share a message of protest today, where would you place it? How would you get the word out?

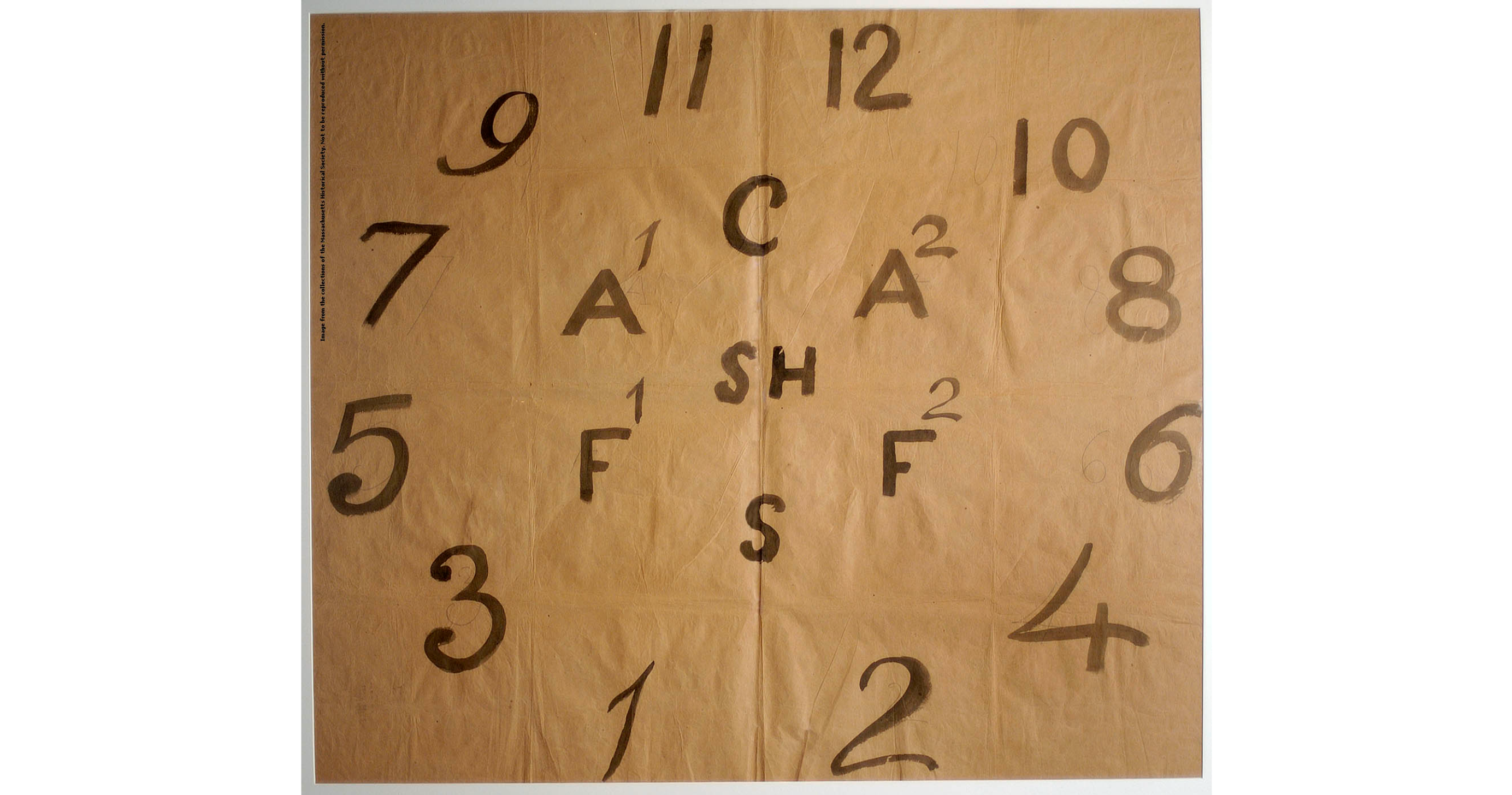

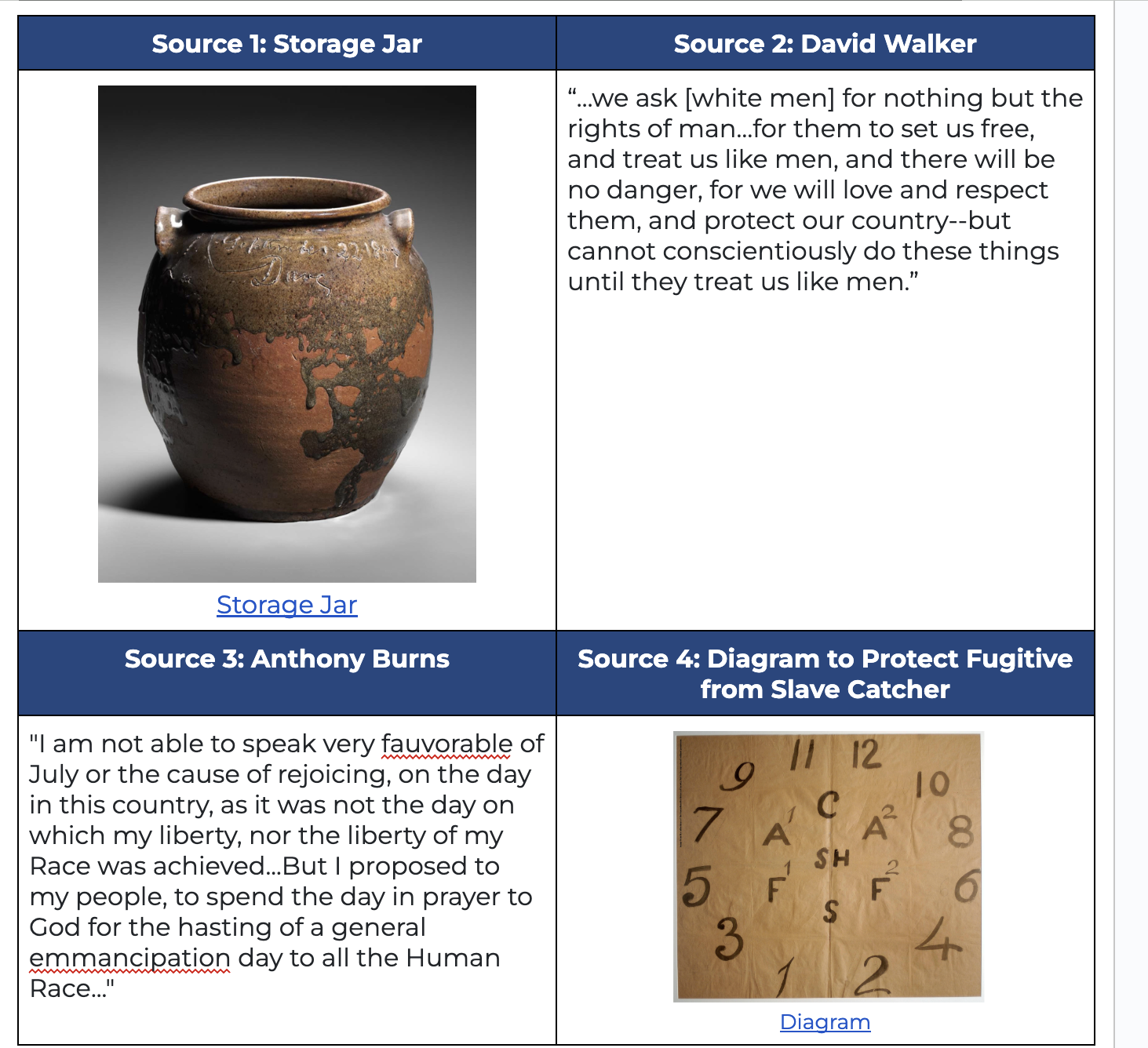

Diagram to Protect Fugitives from Slave Catchers, Anti-Man-Hunting League, ca. 1854-1859

Massachusetts Historical Society

Quick Info

The 1850 Fugitive Slave Act made it legal for enslavers to travel to free states like Massachusetts to capture enslaved people who had freed themselves and escaped north. In the 1850s, Black abolitionists in Boston housed and protected fugitive slaves, and led several efforts to free people who had been caught and jailed. In the early 1850s, Boston saw several high-profile attempts to free freedom seekers (fugitive slaves)from slave catchers. In 1854, group of white abolitionists, including minister Theodore Parker, formed a secret organization called the Boston Anti–Man-Hunting League. Their goal was to make it as hard as possible for slave hunters to operate under the Fugitive Slave Law.

This diagram shows their plan: six members would restrain a slave hunter attempting to abduct a freedom seeker (fugitive slave), while twelve others formed a circle to block anyone from interfering. The idea was to protect freedom seekers and create enough resistance that slave hunters would avoid Boston.

The League met for two years but never used the plan. In 1855, Massachusetts passed a Personal Liberty Act that protected fugitives and barred state officials from helping to capture them. Burns’s case was the last time the Fugitive Slave Act was enforced in the state.

Guiding Questions

What form of resistance is the Anti-Man Hunting League taking based on this diagram?

What does the name of the group suggest about how members viewed the Fugitive Slave Act?

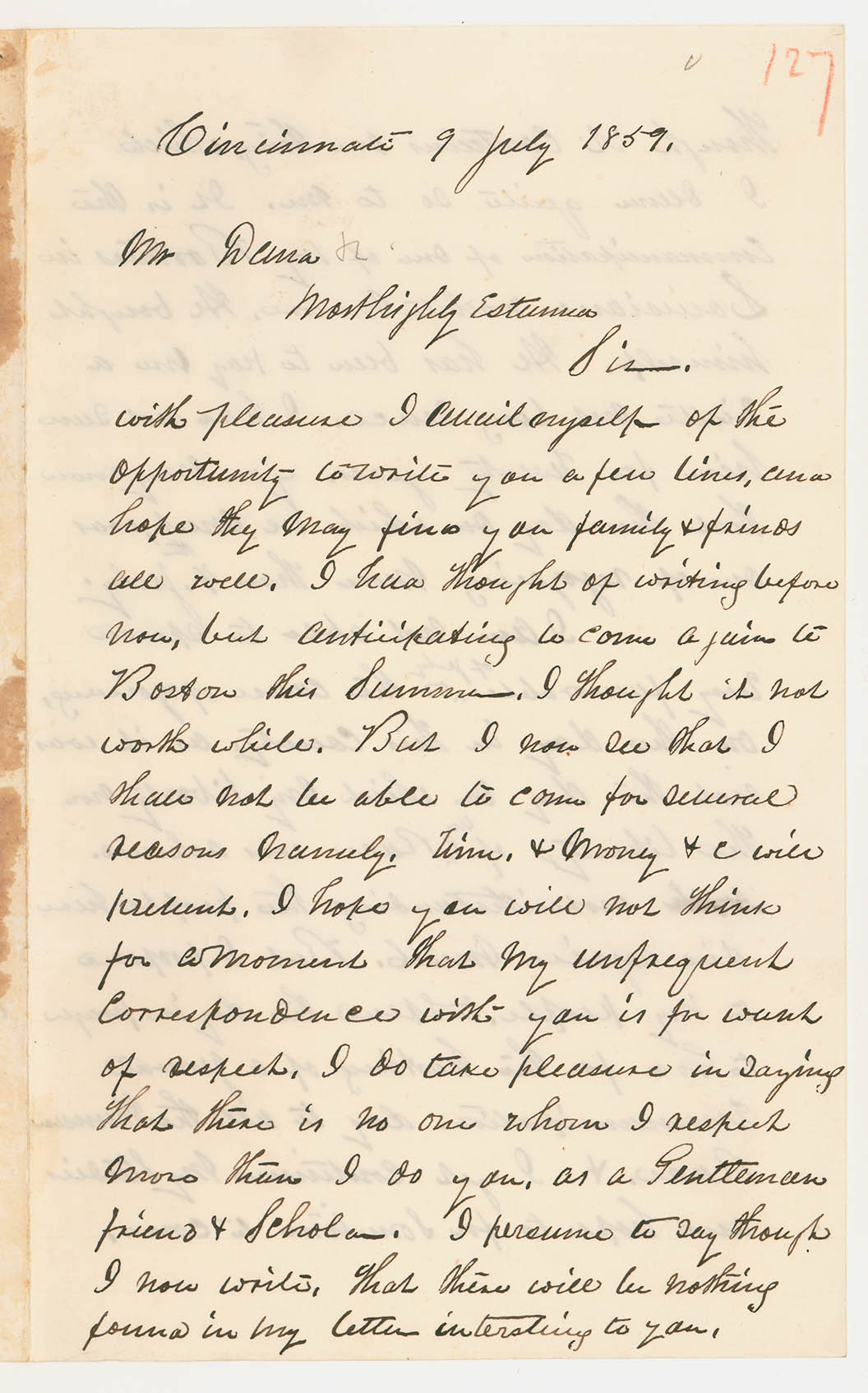

Letter from Anthony Burns to Richard Henry Dana, Jr., , 9 July 1859

Massachusetts Historical Society

Quick Info

In 1854, Anthony Burns freed himself from slavery in Virginia and escaped to Boston.. He was soon captured under the Fugitive Slave Law. His arrest sparked massive protests and a failed rescue attempt, and federal troops ultimately forced him back into slavery as 50,000 Bostonians lined the streets in outrage. Supporters later purchased his freedom, and Burns returned north, studied for the ministry at Oberlin College, and continued his work in Black religious and abolitionist communities until his death in 1862.

On 9 July 1859, Burns wrote a letter to Richard Henry Dana, Jr. in which he describes a visit from his brother who had recently bought his own freedom; discusses his reasons for not celebrating the fourth of July.

Guiding Questions

What, who, and how do Americans celebrate on the Fourth of July?

How did Burns celebrate? What reasons does he give for not wanting to celebrate like other people?

William Matthew Prior, Three Sisters of the Copeland Family, 1854

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Quick Info

This painting shows three sisters: Eliza (at left, about six years old), Nellie (center, about two), and Margaret (at right, about four). Their father, Samuel Copeland, a Black secondhand-clothing dealer and real-estate investor, lived in Boston and then Chelsea, Massachusetts.

As a prosperous middle-class family, the Copelands were able to afford having portraits painted of their children. William Matthew Prior, a white self-taught artist who lived in East Boston, was also an activist and abolitionist. Prior made this painting of the three sisters as well as a separate painting of their brother James.

Artists and sitters (the people posing) often choose specific clothing and objects for a portrait to signal something about the people pictured. For instance, the book in Eliza’s hand suggests that Eliza knows how to read and that her family values education. The sisters’ off-the-shoulder dresses, necklaces, and ribbons were fashionable at the time and showed the family’s wealth.

Guiding Questions

What does each sister hold in their hands? What might that tell us about them?

What would you include in a portrait of yourself? What would you want to highlight about who you are and your life in Boston in 2026?

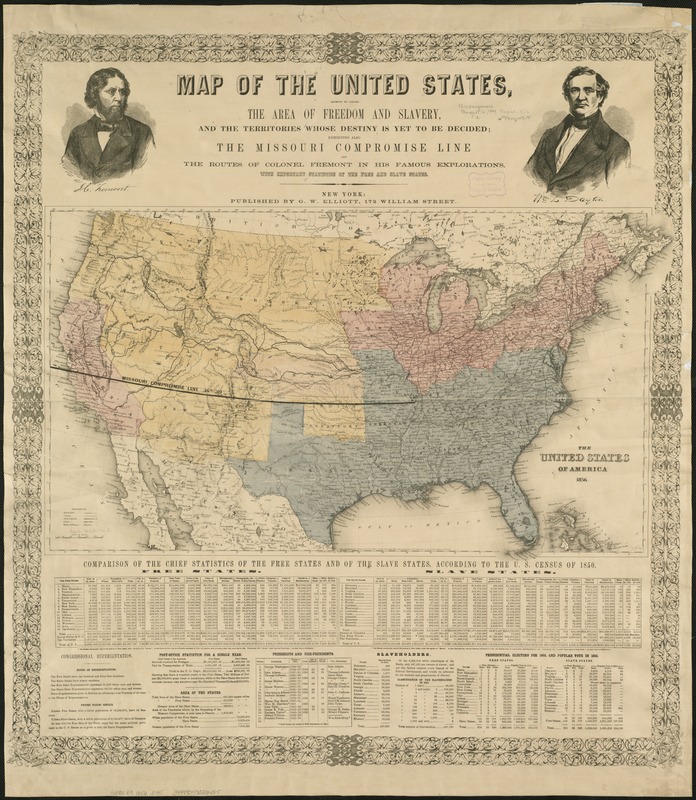

Map of the United States, showing by colors the area of freedom and slavery, and the territories whose destiny is yet to be decided, 1856

The Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library

Quick Info

This broadside (single sheet of paper) was published as a campaign poster supporting the Republican Party's first presidential bid in 1856. The map demonstrates how divided the nation was at this time. There is a legal boundary line between slave and free states, and the mapmaker incorporates census dates to highlight the differences in economic and educational values across the country.

The map clearly marked the 1820 Missouri Compromise line, which had defined the boundary between free and slave states. However, the passage of the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act nullified this long-standing compromise line, and potentially opened the entire western territory to slavery because it sanctioned “popular sovereignty,“ whereby citizens of each territory could vote on the slavery issue.

Guiding Questions

What data has the map maker called out? Where are there large gaps or differences? For example, how many public libraries are there in Massachusetts versus Virginia?

How does the map maker show how the country is divided?

Suggested Activities

Activity One

Grade 5 (IH Unit 3 Lesson 19)

Use the six objects above in addition to or in place of the sources used in Investigating History Grade 5 Unit 3 Lesson 19.

Activity Two

Grade 5

Graffiti Wall, also known as “Chalk Talk,” is a shared writing space where students record comments on a topic or respond to one or more primary sources.

The purpose of this instructional strategy is to help students hear or view each other's perspectives.

Teacher Preparation:

Select materials and questions: Choose the guiding questions and objects students will respond to, and that meet the goal of your lesson.

Prepare the space: Arrange a large area where students can write, such as a whiteboard or chalkboard.

Suggested prompts:

When preparing for this activity, select the object(s) and guiding question(s) that can lead to multiple answers or perspectives.

For example, you might have students respond to the guiding questions that accompany Anthony Burns to Richard Henry Dana, Jr., Letter, 9 July 1859:

What, who, and how do Americans celebrate the Fourth of July?

What reasons does Burns give for not wanting to celebrate like other people?

Student Instructions:

Discuss expectations: Review discussion protocols and clarify what constitutes an appropriate response.

Silent Response (Optional): Remind students that this is a silent activity and that they should write (or draw) legibly for others to read.

Begin writing: Invite students to write comments, questions, or reflections on the graffiti wall. Allow 5–10 minutes for students to contribute.

Group reflection: After writing, hold a discussion. Ask students to summarize what they notice on the wall, highlight areas of agreement, and identify points of disagreement.