As part of her first week of work, we spoke with Emily Bowe, the new Assistant Director at the Leventhal Map & Education Center. Emily is joining the team after finishing her master’s degree at Parsons School of Design at The New School, where she focused on community data practices, urban infrastructure, and mapping.

In her role as Assistant Director, Emily will coordinate and manage key aspects of the Center’s administration and operations, while also leading project-based work on themes connecting cartographic collections and geographic visualization to present-day issues on topics such as urban studies, community history, and the digital humanities.

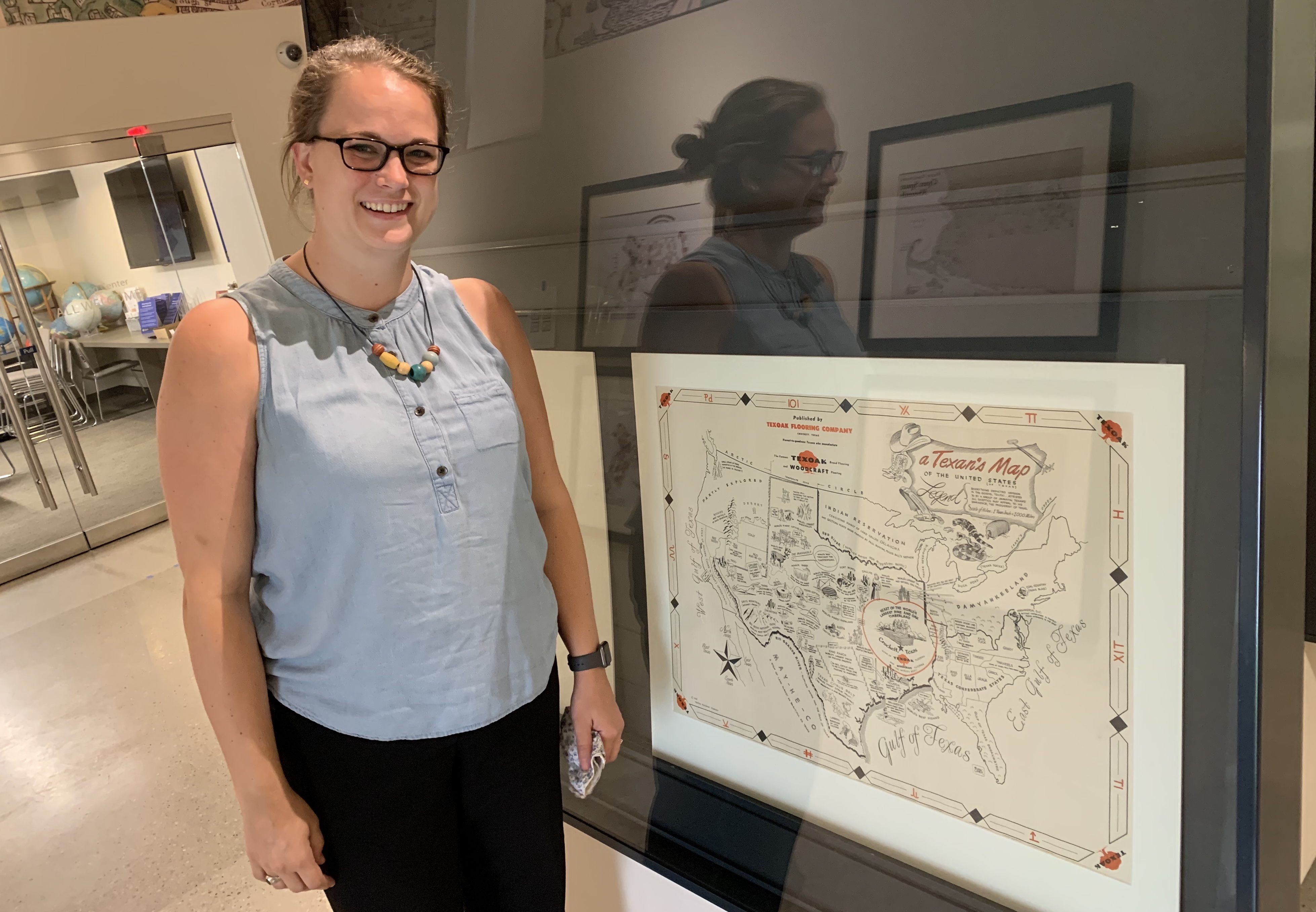

Emily takes a look at the bragging Texas map as we install Bending Lines

Garrett Dash Nelson: Emily, we’re thrilled to welcome you to the team. Can you share a little bit about your background and what got you interested in the work of the Leventhal Map & Education Center?

Emily Bowe: I’m so happy to be here. The work of the LMEC is such a brilliant mix of things I’ve been interested in for a long time—being here feels like finally getting to weave together so many topics that I find fascinating. In college, I was a bit of an odd duck. Officially, I was registered in lots of environmental science and GIS classes, but spent all of my free time in the journalism school learning about digital media and how this new form of access changed the way that stories could be told.

An 1890 map of San Antonio from the Library of Congress

When I graduated, I started working in San Antonio, Texas. Like Boston, San Antonio has very deep urban history. As part of my job, it was important for me to understand a lot of this history, so I started turning to online records and historical maps that helped me get to know my new home. So much of that city’s development can be unpacked by learning about the city’s role as a meeting point culturally, geographically, and politically.

In my free time, I tried to start making maps of my new city as a way of learning more about where I lived, but realized I didn’t have access to the same GIS licenses I’d had in college. So, I started teaching myself some open-source geospatial programs and began tinkering with web development. By peeking inside of other projects that I admired, I taught myself how to build basic web apps and websites.

When I came into graduate school, I was interested in finding some ways to bring together my professional experiences in architecture and urban development with my personal interests in web mapping, community-based data, and the creative storytelling powers of the internet. I found myself enrolled in classes in urban planning, sociology, data visualization, and design & technology. So, you can see why the work of the Leventhal Center felt like finding kindred thinkers!

GN: I’ve heard you call yourself a “map nerd”, which is certainly a badge of honor around here. Can you point to a specific experience that might have piqued this interest?

EB: Well, growing up in Texas, I spent a lot of time in the car. There was always a Mapsco road atlas in the back seat of my parents' cars and I found that to be pretty entertaining when confronted with long drives. I loved finding the pages for places I knew in person and then flipping the pages to try to imagine parts of the city I hadn’t been to.

But overall, I credit a high school research paper on Daniel Burnham and the World’s Fair in Chicago for helping me realize my early interest in urban planning and cities. (Thanks to my AP US History teacher, Mr. Kramer, for telling me Jane Jacobs might be an interesting read for my background research.) I was particularly fascinated with the graphics and the maps that were produced as part of the planning for the World’s Fair. Many of them ended up laying the groundwork for the 1909 Plan of Chicago, which featured maps and illustrations that were illustrating a potential future more than representing any kind of “objective” reality on the ground. It was then that I started to really pay attention to the ways that maps can be used to push a particular point of view or agenda. If only the Bending Lines exhibit had been around when I was in high school!

An 1892 Chicago map from Rand, McNally & Co. showing the site of the World’s Colombian Exposition (also known as the World’s Fair)

GN: What work at the Center are you looking forward to?

EB: I’m can’t wait to dive in to the planning for our 2022 exhibit More or Less in Common, which will focus on themes of environmental justice in cities. It’s such a fantastic opportunity to learn about the environmental history of Boston and also create space for conversations about power and equity in planning and urban development.

I’m also really eager to see firsthand the work of our amazing education team. For example, I was so drawn to the Maptivists program when I first learned about it and I’m hopeful that I can learn from our team about that kind of student-centered work, both in-person and online.

GN: Last question: you’ve just moved to Boston from New York. What are you most excited about as you get to know Boston?

EB: All the amazing outdoor public space! I live near Franklin Park and can’t wait to run and bike through to explore while the weather is nice. I’ve also got a growing list of museums that have been recommended to me, so I’m planning out my weekends accordingly.

That said, I’d love nothing more than if folks reading this wanted to email me their favorite spots in Boston. I’m building my list of things to do and would love to say hello and learn from the broader Leventhal Center community!

An 1885 general plan of Franklin Park drawn by Frederick Law Olmstead and John Charles Olmstead from the Norman B. Leventhal Center Collection.

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.