In this interview, we talk with the newest member of the extended Leventhal Map & Education Center team: Dr. Alexandra Montgomery, who joins the American Revolutionary Geographies Online project as a postdoctoral fellow. The project—ARGO for short—is a partnership between the Leventhal Center and the Washington Library at Mount Vernon. Together, we’re building a new portal that brings historic collections and interpretation together to show how maps and geography can reshape our understanding of the era of the American Revolution.

Dr. Montgomery will be coordinating many of ARGO’s first initiatives—and also providing her own expertise on the subject! She earned her PhD from the University of Pennsylvania in 2020, and has previously worked with the Institute for Thomas Paine Studies, the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, and the American Philosophical Society, where she assisted in the creation of a book and digital exhibition on a collection of land deeds from Chester County, Pennsylvania. She’ll be based at Mount Vernon, but working closely with the Boston team as well.

Garrett Dash Nelson: Alexandra, we’re so excited to have you as part of the ARGO project. Tell us a bit about your background. How did you get interested in history, and what sorts of research are you most passionate about?

Alexandra Montgomery: It took me a while to come to history. In undergrad—and I think this is pretty common—I didn’t know what I wanted to do and was just generally very unmotivated. I even considered dropping out, as I kind of felt like all I was doing was wasting my and my parent’s money. What changed things was lucking into a summer position as an assistant curator at a local farm museum, where I assisted in inventorying the collection, among other things. It completely blew my mind. I’d always been vaguely interested in old things but for some reason it never clicked with me until then that it was a subject that a person could seriously study and make into a career. I immediately switched my major and the rest was, I suppose, history.

My research interests came out of a similar story. I grew up in Halifax, Nova Scotia, which was founded in 1749 as kind of imperial experiment, part of a larger effort to make the far northeast of North America more “British” as less Indigenous and French. I first started digging into that history at another summer job during undergrad. I was a tour guide at Halifax’s oldest burying ground, and I became completely fascinated by that early period and especially the links between the new settlers in Halifax and New England, which eventually became my master’s thesis.

A view of Halifax in the Atlantic Neptune from the Library of Congress collection

My PhD research came out of questions I had about Halifax’s founding. Very uncharacteristically for the British, Halifax was founded using Parliamentary money and initially settled with folks directly recruited by the Board of Trade. In my book-in-progress I argue that what the British were doing there was trying to harness and weaponize the dispossessive power of settler families in order to weaken Indigenous and French power and stake a stronger claim to the region. In my work I call this “weaponized settlement.” What I mean by that is that folks in power saw white settler families as a means of winning territory and deciding geopolitical disputes in a way analogous to battles. I think it was an idea that actually had broad currency throughout both the British, French, and early American empires and states, but a place like Nova Scotia and elsewhere in Maritime Canada and northern New England makes these kinds of ideas more obvious because they were getting less un-subsidized white migrants than agriculturally rich regions like the Ohio Country. Within that, I’m especially interested in how conflict over where and how white settlers should live in North America influenced the break between the colonies and the Crown in the 1760s and 70s.

GN: What are some ways that you’ve used maps of the Revolutionary War period to help reframe our understanding of that historical period?

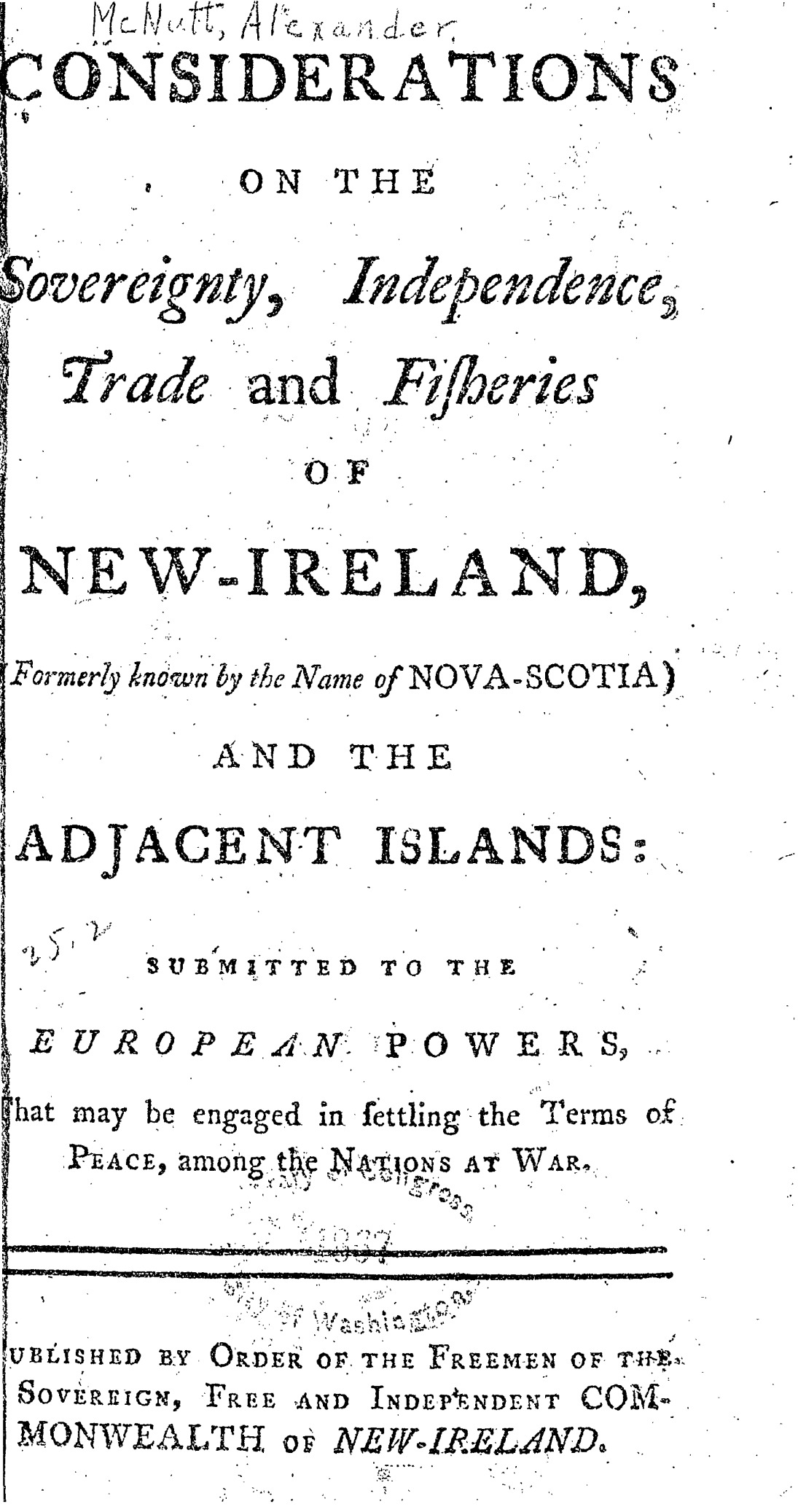

The title page from McNutt’s Considerations on the Sovereignty, Independence, Trade and Fisheries of New Ireland

AM: One of my absolute favorite maps is a map of Nova Scotia annotated by one of the more colorful characters in my research, a land booster named Alexander McNutt. To put it mildly, he was very passionate about ensuring land was given to smallholding settler families freehold with no strings attached, and was absolutely convinced that there was a conspiracy among those in power in the province to turn it into a vast exploitative feudal manor. In the map, he’s gone in and colored the land of people he thinks are exploitative landlords in yellow, and constrasted it with land reserved to him, colored in red. I’d read his (many, many, many) memorials but it wasn’t until I spent time with the map that I really understood the scope of his claims, as well as the fact that they were in based in more than a kernal of fact. The yellow lands he highlighted occupied some of the most strategically important land in the province, were in fact owned by government officials and insiders, and, as far as I have been able to tell, were organized as estates with tenants holding land under variously harsh leases. McNutt is generally portrayed in the literature as an absolute loon, but this map made me realize that not only did he have a point, but that it was a line of concern and argumentation that intimately linked what was happening with land in Nova Scotia in the 1760s with broader debates of the imperial crisis era throughout the British colonies of North America.

GN: Are there any maps in the existing Revolutionary War Collection of Distinction that you find particularly intriguing?

AM:I’m completely fascinated by the so-called “red lined map,” the version of the 1755 John Mitchell map of North America that was owned by George III. In additon to the red line(s)showing discussed borders between the new United States and what later became Canada, there are several other manuscript annotations showing borders from the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht and other diplomatic negotiations before the American Revolution. The Mitchell map itself is already so dense and fascinating that between that and the annotations you could spend the rest of your life researching and writing about it.

John Mitchell’s “red lined map,” from the British Library collection

GN: What’s one map that isn’t availability digitally right now that you would like to see digitized?

AM:I have a huge list of maps I’d love to see come online for purely selfish reasons, ha. Of course, that’s also true of most other historians I know, which really speaks to the potential impact of the project. There are so many barriers to getting to really study maps of this era in person. Speaking more generally, though, I’m very excited by the possibilities of ARGO to bring more obscure manuscript maps into direct conversation with better known published ones, and to bring together maps that are intellectually or historically connected but physically separated and held by different institutions.

Want to keep track of future ARGO developments? Follow us or the Washington Library on social media, or join our mailing list.

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.