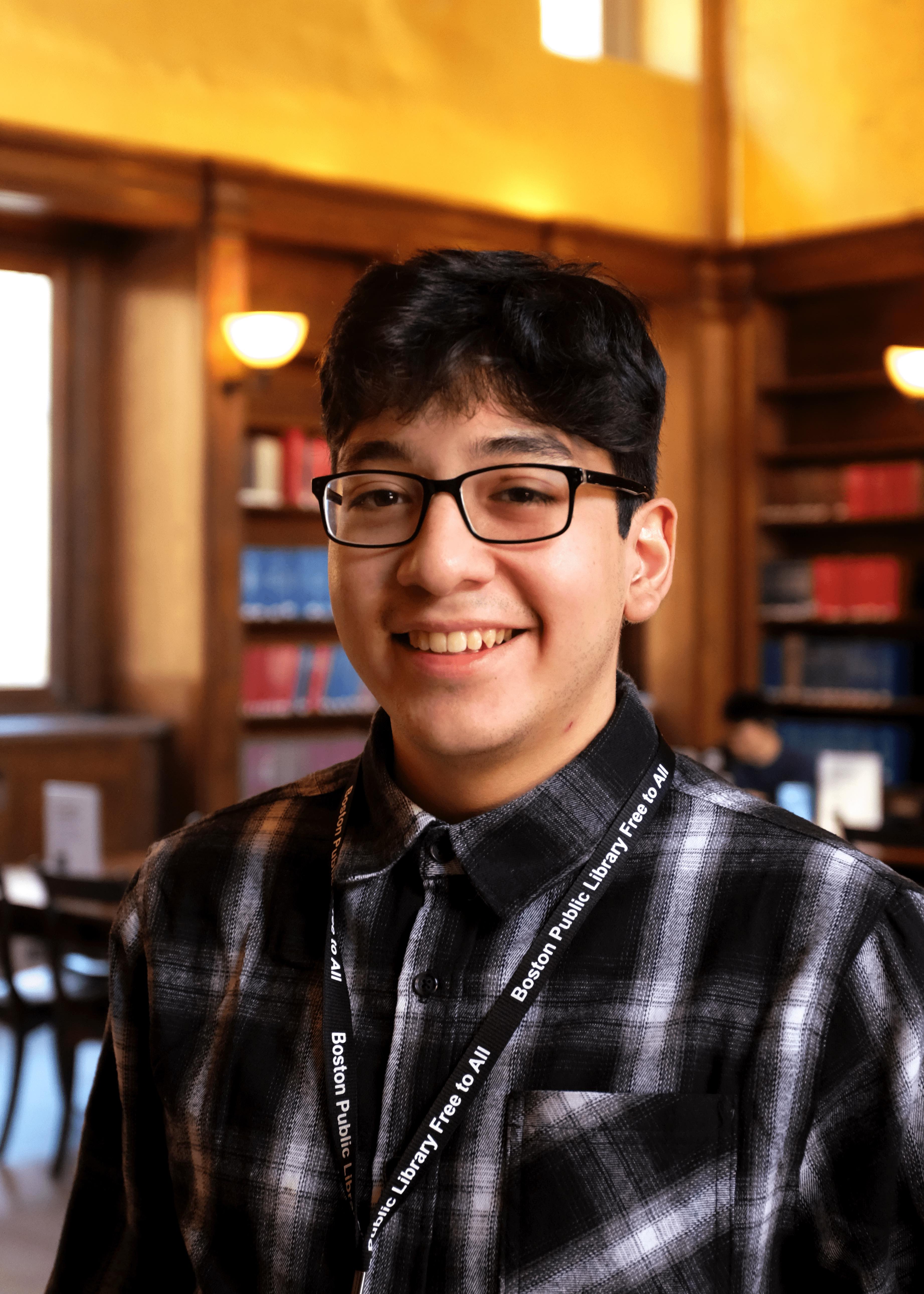

We’re excited to welcome Patricio Pino to the team as the Spring 2023 co-op student serving as Visitor Services & Exhibition Assistant. He is a student at Northeastern University studying English and Anthropology. We sat down with Patricio to learn more about his interests and background.

Patricio Pino

Tell us a bit about your background. What are you currently studying at Northeastern and what made you choose to work at the Leventhal Center during your co-op experience?

I’ve lived in Massachusetts for basically as long as I can remember, but I was born in Peru where most of my family still lives, so I’ve always had something of a split cultural experience between my personal life and life in America: at home or at school, Spanish and English, etc. There’s an inherent diversity there that I’ve grown to value as a source of inspiration from what would otherwise be situations of distance or divide, something which I see as very influential in molding my interests and the core decisions I’ve made in life, for example in choosing to study English and Anthropology at Northeastern, and now deciding to work at the Leventhal Center.

This 1656 map of Peru charts the course of the Amazon.

My academic interests, in writing, literature, or anthropology, are unified by a human struggle to create (or find) meaning, whether in stories, artworks, rituals, traditions, or the pursuit of knowledge. I think the process of creating something completely new and impactful out of a diversity of seemingly contradictory influences is the same in both the work of an artist and a researcher, as well as in the seemingly authorless process through which the “culture” of our day-to-day lives is produced.

The Leventhal Center is an institution fundamentally oriented towards both the public and the academic, and it is focused on the artifacts which most epitomize meaning-making as a process which can encapsulate and subsume distances, namely: maps and geography. Now that I’m here I continue to be fascinated by new items in the collection or by new aspects of the current exhibition I hadn’t noticed before. Most importantly, I continue to be certain that the Leventhal Center represents the intersection of so much of what I hold as critical to my academic and creative life.

What’s your earliest memory of looking at/working with maps?

There’s this very beat up world map (which is older than me) with pictures of every national flag, which was a mainstay of my bedrooms as a kid. I think partly because it was so beat up and outdated it gave me all sorts of questions to investigate, like, what is a Yugoslavia? Why are only some republics people’s republics? What even is a republic? In all seriousness, while the human aspect—in politics, global cultures, or world boundaries—is definitely something which still fascinates me, I realize that there has always been a geographic aspect to the fundamentally necessary imagining of place which is required by any study of human communities over time or distance. A world map can be fascinating because it promises the distantly exotic and unknown. As a child this fascination was pure imagination and curiosity, I hope that’s something that I haven’t fully lost, but regardless I do know that human imagination across distance will continue to be a part of my life, just as more of an object of study or interest.

You’re finishing up your third full week with us and your first two weeks were marked by lots of exhibition install! Now that the two exhibitions (Building Blocks and Becoming Boston) are up, are there any parts that were particularly fun to see come to life or that you find yourself particularly drawn to?

Sitting in the gallery attendant’s desk provides a somewhat privileged observer’s perspective to a lot of the day-to-day happenings which our work facilitates. So not necessarily any of the specific panels or artifacts which I helped assemble, but being able to see “the point” of it all take shape as we accumulate visitors and hopefully shape people’s viewpoints to some degree. Overhearing conversations about personal histories, the lives of grandparents or great-grandparents throughout Boston, immigration narratives, sentimental places, buildings or institutions, and the audible shock which accompanies a new insight or discovery, all drive home the point that much of our work finds purpose in its eventual audience.

An honorable mention here for something overheard, is the work of our K12 education team, who had their first school visit of the new exhibition just last week. It was absolute utter pandemonium. It was pretty incredible. Seeing a gallery which is frequently excessively quaint overrun by fourth graders, and seeing them (mostly) actually listening to a lesson basically based on fire insurance atlases, I think is reason enough to love the work that’s done here, and to definitely not mess with the K12 education team.

Have you discovered anything fun on Atlascope?

Note the handwritten edits and street number changes on this details of the 1938 Bromley Atlas of the City of Boston.

The countless scrawled annotations and edits! A very big theme of Building Blocks is a focus on picking out the actual lives and experiences from the very technical and administrative details of something like a fire insurance atlas. I think there’s no better example of this than the pencil marks, handwritten notes, and glued on edits, which are so human yet so easily missable from the distance at which we present our work. On Atlascope there’s an extra layer of that technical distance thanks to the digital aspect stitching together different plates and overlaying disparate atlases, but the literal closeness which you get—in being able to zoom and access other viewers’ annotations—means that I’ve been having a lot of fun looking for as many of these little human artifacts as I can.

What are you excited about working on in the next six months?

Because my time here started with the very upfront and crazy installation process for Building Blocks, which I’m only now getting to familiarize myself with at a slower pace, I’m looking forward to witnessing the development process for our next exhibition. Hopefully in a way where my first impressions won’t be of mildly panicked gallery arrangement (though it was pretty exciting). I guess I’m interested by the kind of inverted exhibition creation process which I’m going to get, where my time at the Leventhal Center begins with the very end of the process and ends before the next exhibition is completed.

I know you’ve only just gotten here, but do you have a favorite map in the LMEC collections?

Something of a rail service is pictured in the the Cuzco region of Peru in 1929.

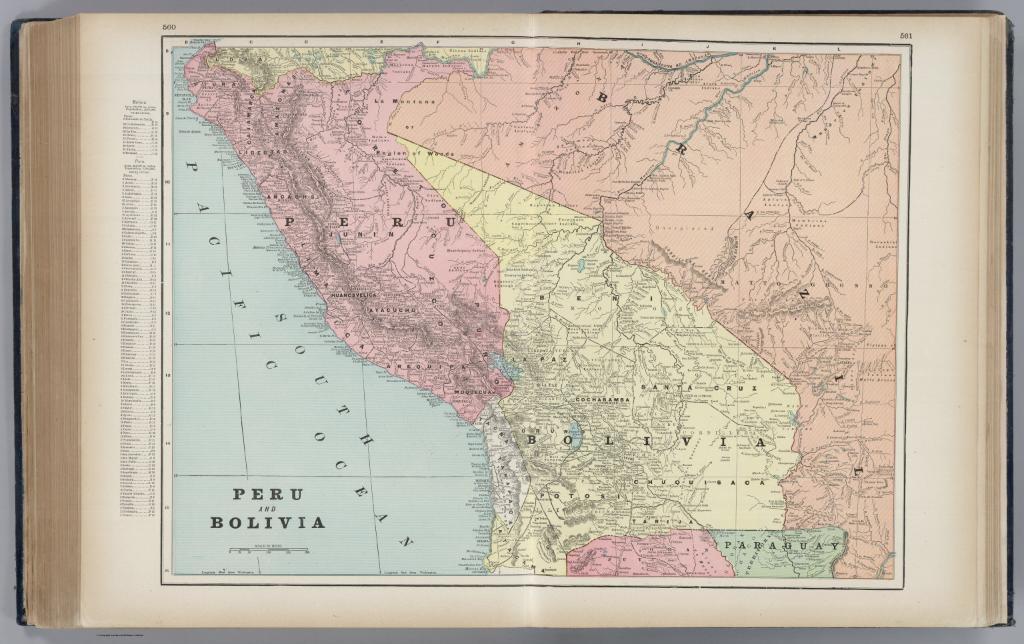

Thanks to our incredible From the Vault program, I was able to familiarize myself with the very exciting 1899 Cram’s Standard American Railway System Atlas of the World (!). Which, apart from being thrilling, was actually pretty dense in curious little details in addition to being aesthetically pleasing. In particular its map of Peru and Bolivia, which represented a pretty critical moment in the history of foreign interests and industrial exploitation in the region, uniquely depicted spatially in the form of railway lines radiating from the coast towards the interior.

A page of the 1899 Cram’s Standard American Railway System Atlas of the World shows the railroads crossing Peru and Bolivia.

Additional little details further made this map a good example of the density of information which geography can depict. For example, the map lists different indigenous peoples exclusively in the Amazonian regions which though not directly reached by rail, were in the process of entering a pretty brutal period of colonial exploitation which continues to the present. The histories embedded in the smaller intricacies of this map I think highlight part of the significance of our work: that across the quarter-million maps and artifacts in our collection, all scattered across the globe and throughout history, there is always the potential for insight or education with critical relevance to the issues of today.

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.