On August 8, we hosted From The Vault — Cartography at Length: The Longest Maps in the Library.

If we organized maps by something like their length, would we still see patterns emerge? Could we learn something about geography and history from looking at the longest maps in a library? It turns out, the answer is “Yes.”

During Cartography at Length we looked into some of the longest and tallest maps in the LMEC archives, all of which are at least 3 times as wide as they are tall (or vice versa). From rivers to railroads, from green parks to gold rushes, these maps document how cartographers have fixated on long landscapes—including one 12-foot long map of the Boston Marathon, printed on a receipt!

John J. Pratt, Map of the route to the Kansas gold mines : prepared from government and other surveys : showing the most direct railroad routes from the Atlantic cities to the Missouri River (1859)

Width and length: 81 x 20cm, Aspect ratio: 3.8

Angular black lines stitch together cities from Boston to Santa Fe in this 1859 map of the Gold Rush. The railroad routes shown here stretch thousands of miles and would be traversed by over 300,000 gold-seeking settlers between 1848 and 1861. Maps like this one, which document where gold was and how prospectors could get there, encouraged the desire for wealth and riches just as much as the gossip and hearsay that traveled back east from California.

The parts of central Colorado marked “Gold Region” are now home to familiar cities; “Pikes Peak” would become Colorado Springs, for instance, while the name “Denvir City” is stuffed behind a much larger label for “Mines.” Just visible at the bottom of the map, modern-day Oklahoma is listed as “Indian Territory”—a reminder of the millions of Indigenous lives and distinct societies that were obliterated or forcibly relocated during this period of genocidal western expansion and settler colonial capture.

Geo. H. Walker & Co., Map of Commonwealth Avenue Street Railway Company, and connecting lines : showing route to Norumbega Park (1898)

Width and length: 54 x 14cm, Aspect ratio: 3.8

On this 1898 map of the Commonwealth Avenue Street Railway Company, pastels colors distinguish different towns in the Greater Boston area. A bright red railroad line leads to Norumbega Park, bursting at the western edge of Newton’s seams with carnival attractions: soda fountain, boat house, merry-go-round, and much more. In the late 19th century, private railway companies often built destination parks at the end of their line to encourage patronage and incentivize ridership. In the case of Norumbega Park, riders were also incentivized by “the long open cars”—proudly built by J.M. Jones Sons of West Troy, N.Y.—which presumably delivered a luxurious journey to this luxurious destination.

Henry M. Wightman, Plan of proposed Muddy River improvement, showing contours : July 23, 1881 (1881)

Width and length: 94 x 22cm, Aspect ratio: 4.27

How does one “plan” a river? Originally part of the Back Bay salt marsh, the narrow, tidal Muddy River formed the boundary between Boston and Brookline. By 1880, urban growth polluted and frequently flooded the once-flowing tributary. That year, Frederick Law Olmsted proposed improvements to the Muddy River. This plan—drawn by a City of Boston engineer one year later, in 1881—depicts the contours of Olmsted’s proposal with red lines.

Created for the Park Department, the plan represents a point-in-time snapshot of the landscape known today as the Back Bay Fens (although the provisional title of ”Back Bay Park” is visible at the eastern edge of the map). Winding from the Boston Common all the way to Jamaica Pond, this plan captures one leg of Olmsted’s famous “Emerald Necklace” park system.

Harbour Commissioers of Montreal, Profile of the river St. Lawrence between Montreal and Quebec shewing the deepening of the ship channel (1878)

Width and length: 97 x 21cm, Aspect ratio: 4.61

This river profile, published in 1878, documents the importance of the St. Lawrence River to the urban network of southeastern Canada. Clocking in at a formidable aspect ratio of 4.6, this chart depicts a wide range different data, including:

- Blue “low water level”: lowest level water could be; want river floor deep enough the largest/heaviest ship would not get stuck (they decided 25' deep)

- Black outline: original floor depth

- Shaded red: what’s been removed to make floor 23' deep

- Crosshatched red: what still needs to be removed to make floor 25' deep

The map highlights the centrality of long, natural features—like the St. Lawrence River—to 19th century urban economies. The river had to be dredged in order to make the landscape navigable for larger vessels, which would improve the productive capacities of the region. Meanwhile, the dredging itself created its own constellation of economic activity; as the map notes under the “Ship Channel” header in the top-right hand corner, the monetary “Expenditure for 20 ft. of depth” totaled $1.2 million in 1878, over $38 million today when adjusted for inflation.

James F. Baldwin, A plan & profile of the Boston & Lowell Railroad [1836?]

Width and length: 101 x 20cm, Aspect ratio: 5.5

Railroads and canals feature prominently in the category of “long maps,” and oftentimes, these long landscapes appear beside one another in the same maps. Such is the case with this 1836 map of the Boston & Lowell (B&L) Railroad, in which the railroad itself follows the contours of the Middlesex Canal (labeled “M. Canal” or just “Canal”). The B&L Railroad Company incorporated in 1830 and faced pushback from the canal investors, who feared the railroad would render their canal obsolete. These economic disputes translated to political ones, as railroad companies needed to convince the Massachusetts state legislature to fund their projects. In the original charter of the B&L Railroad Company states:

“no other railroad than the one hereby granted, shall, within thirty years from and after the passing of this act, be authorized to be made, leading from Boston, Charlestown, or Cambridge, to Lowell, or from Boston, Charlestown, or Cambridge, to any place within five miles of the northern termination of the railroad hereby authorized to be made.”

In other words, this long map also depicts how geography and monopoly intersected on the tracks of a railroad.

Richard P. Mallory, Panoramic view from Bunker Hill Monument (1848)

Width and length: 120 x 17cm, Aspect ratio: 7

Looking towards Boston from the Bunker Hill Monument, this 1848 panoramic view captures Boston’s regional geography in a single scene. The “Laboratory Chimney” (#96) sputters smoke over Roxbury, while sailboats pockmark the Boston Harbor from Long Wharf to Cunard’s (#38). The Fletching (#109) and Maine (#87) railroads carve a triangle past the “McLean Insane Hospital” (#114), and the now-bustling city of Somerville (#119) is represented with open pasture and empty fields. Distant ecological features like Mount Monadnock (#125) and the White Mountains (#133) are represented on the horizon line.

Altogether, the view positions mid-19th century Boston as the center of a much wider system, tying together the urban, coastal, and mountainous regions of New England as parts of the same whole.

Board of Harbor and Land Commissioners of Massachusetts, Plan of location of projected ship canal from Taunton River to Boston Harbor, through Weymouth Fore River … Frank W. Hodgdon, engineer (1902)

Width and length: 174 x 18cm, Aspect ratio: 9.6

Some plans just fall through. This very long map from 1902 depicts a ship canal from the Taunton River to the Boston Harbor that would never be built. Originally devised at the turn of the twentieth century, the Taunton-Weymouth canal was to span 35 miles and cost nearly $58 million at the time (for reference, the Panama Canal is 50 miles long). The price tag became the downfall of this ambitious project.

Those familiar with the South Shore of Massachusetts will be familiar with what happened in its place: the Cape Cod Canal, constructed beginning in 1909, which chiseled 17 miles off the Massachusetts coast and saved seafaring vessels en route to Boston an unseemly detour around Cape Cod.

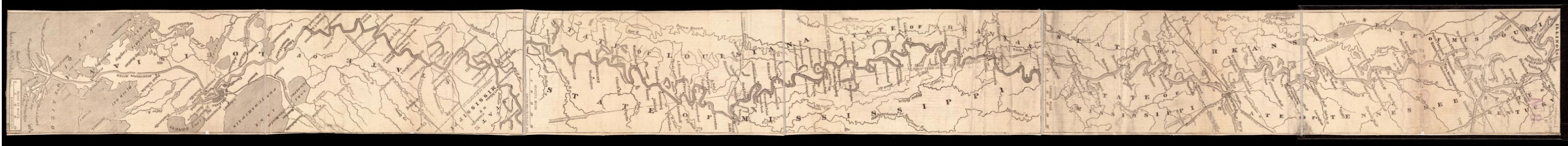

Map of the Mississippi River, from Cairo to the Gulf of Mexico, showing the position of the rebel fortifications at the mouth of the River, those already taken and those remaining to be captured, etc (1862)

Width and length: 12 x 155cm, Aspect ratio: 12.9

A large portion of the Mississippi River, from Cairo, Illinois to the bayous of Louisiana, is depicted in this 1862 map. It is detached from an illustrated newspaper published in 1862, which means in its original published context, the map would probably not have been laid out this long. While its primary purpose was to show Confederate fortifications along the mouth of the Mississippi, it also highlights the strange twists, turns, and names that pop up along America’s longest river. Near the border of Louisiana and Mississippi, for example, you’ll note the “Raccourci Cut Off”—a shortcut engineered by the State of Louisiana in 1848 that saved 19 miles on the riverway commute and created a new oxbow lake and island in the process. Legend has it that the ghost of an old paddle steamer still haunts the Raccourci Cutoff to this day.

Aaron Koelker, A map of the Boston Marathon : since 1897 (2024)

Width and length: 5 x 325cm, Aspect ratio: 65

Aaron Koelker’s “A map of the Boston Marathon”—the inspiration for this week’s From the Vault map collection showing—represents the latest in a lengthy tradition of long mapping. An astonishing 65 times taller than it is wide, the receipt map captures iconic Boston landmarks, like the Fenway Citgo sign and Heartbreak Hill, along the Marathon route. Although Koelker considers this map to be part of a “minor exploration of impractically long mapping,” he also admits that the Marathon receipt map does have, in its own way, a practicality:

While the map is mostly meant to be a novelty, I did want to give it some practical function. Back when I ran cross country, I always wanted to know where the uphill sections were so that I could plan where I should speed up or save my energy for an upcoming hill. … the Boston Marathon route has plenty of hills, and I was working at a large enough scale that it made sense to show them (which you can see as hatched sections along the route).

As you ponder the long maps on display here, we invite you to consider their practicality, their impracticality, and the social and geographical contexts that might have driven a cartographer to make such long maps. In some cases, maybe it was to efficiently depict travel routes; in other cases, maybe a long map was the best way to advertise how two places could be connected.

What do you notice when you look at the entire route of the Boston Marathon on a single receipt?

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.