The tale begins in 1807, when a wayward Russian Orthodox monk named Nikita Yakovlevich Bichurin (1777-1853) arrived in the capital of the Qing empire. As the head of the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission, he was tasked not only with proselytizing but also gathering information about the empire's inner workings. But Bichurin, known also as Iankinf or Father Hyacinth, did not behave as a man of the cloth. His thirteen-year tenure was besmirched by disturbing accounts of sexual depravity and misconduct amongst his rank, which led to his unceremonious recall to Saint Petersburg in 1820. Despite the inquisitions into his moral character, there was little doubt as to Bichurin's intellect and curiosity. He studied Chinese and Manchu and published widely on the history, customs, and geography of the Qing realm. To this day, he is recognized as a key figure in Russian Sinology.

Shortly after arriving in Beijing, Bichurin decided to create a map of the city. “It is with this idea,” he wrote, “that during a residence of fourteen years at Peking, I have bestowed all my attention on the most remarkable objects which this capital contains and have undertaken to make the plan of it, accompanied by a description.”

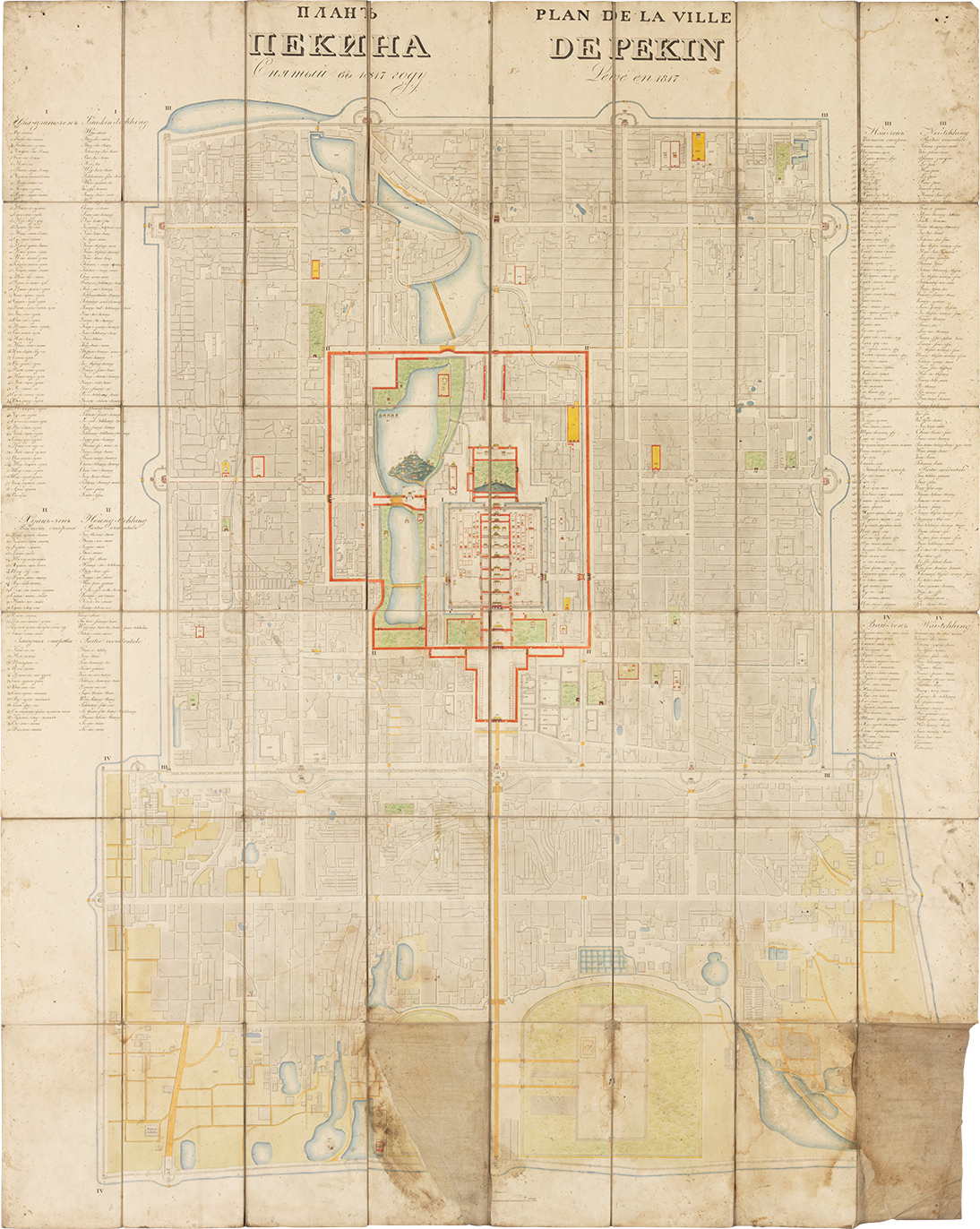

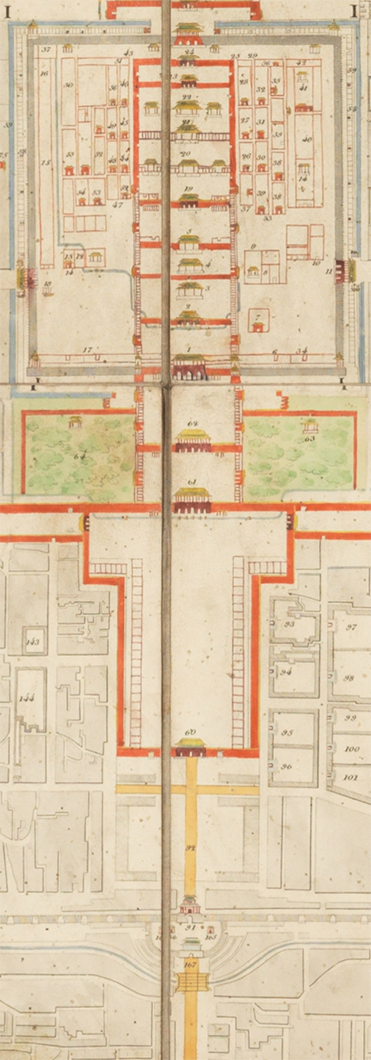

But Bichurin was trained neither as a surveyor nor a mapmaker. Instead, he commissioned an unnamed Chinese person to traverse the labyrinthine city in order to produce a detailed cartographic record. The resultant map, a rare copy of which is now held at the MacLean Collection, would serve as the foundation for a series of adaptations that circulated across continents and cultures throughout the nineteenth century (fig. 1).

Map of the City of Beijing [Plan de la ville de Pekin] is indeed impressive. It presents the maze of walls, gates, houses, temples, gardens, waterways, lakes, passages, and alleyways that make up the capital as a visually cohesive whole. “I can assure the public, that this plan is not one of the number of those with which the warehouses of Peking abound; but has been so recently drawn as the year 1817, and revised with all possible care,” Bichurin declared with confidence.

Designed to appeal to both scholarly and general readers, the map's title is written in both Russian and French, with the latter being the dominant language for academic Sinology at that time. Bordering the map is an index of 185 distinct locations. Instead of translating Chinese place names, the map uses transliterations in both Cyrillic and Roman alphabets.

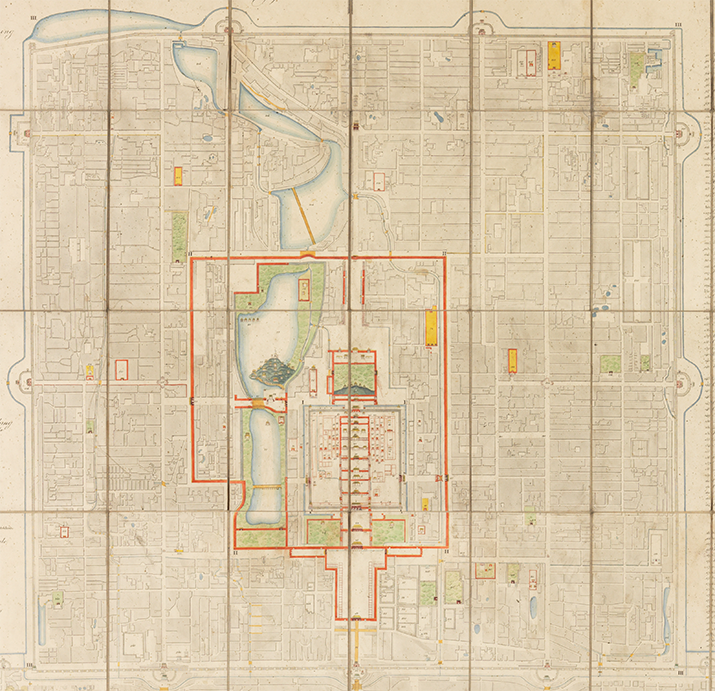

The index is organized according to Beijing's distinctive layout, which consists of four nested sections forming a rectilinear shape often compared to a keyhole or the Chinese character 凸 (C. tu, meaning “protruding” or “convex”). A thin blue line surrounds the entire city, representing the waterways connecting Beijing to the Grand Canal, which runs southward to the Yangzi River.

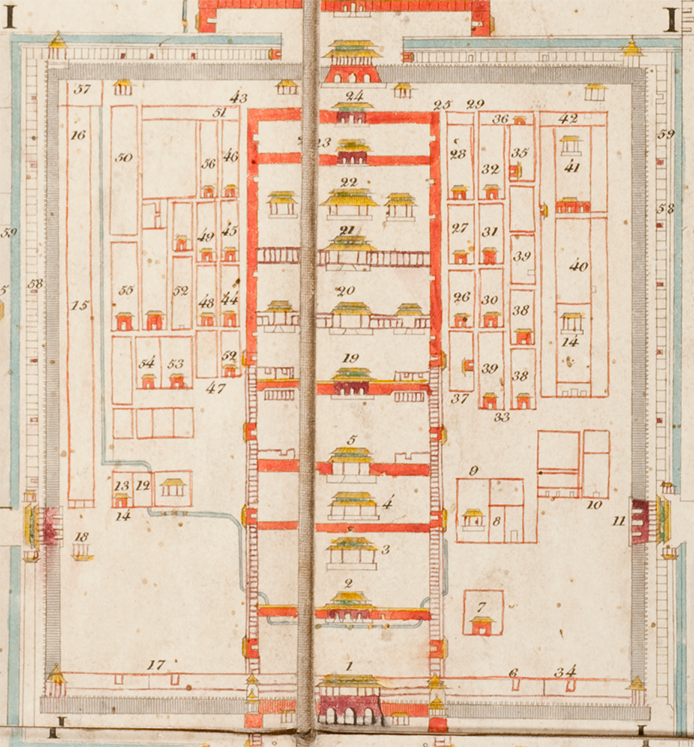

The index begins with sites in “Tseukin-tchhing” [Zijincheng, Purple Forbidden City], the designation given to the emperor's residence during the sixteenth century (fig. 2). By beginning at the symbolic and architectural heart of the city, the map emphasizes the centrality of the emperor and imperial power.

Fig. 2, Detail, Forbidden City, Map of the City of Beijing, MacLean Collection 29889

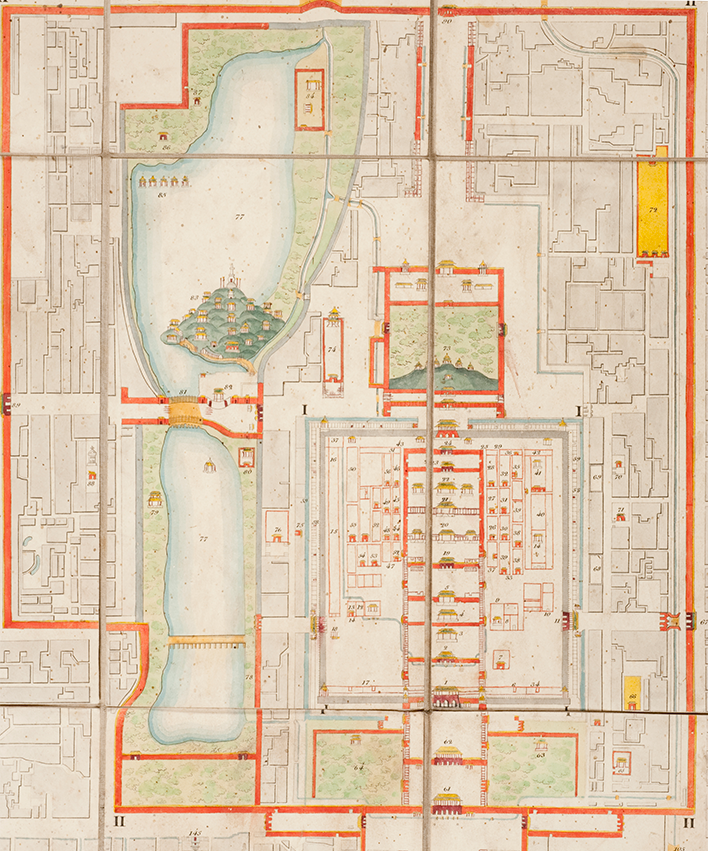

The Forbidden City is nestled within the “Hoang-tchhing” [Huangcheng, Imperial City], which contained mansions and administrative quarters of the Manchu ruling elite, who were organized into military-social units known as the Eight Banners (fig. 3). This imperial enclave is highlighted with bright vermillion to represent the distinctive walls that enclose it.

Fig. 3, Detail, Imperial City, Map of the City of Beijing, MacLean Collection 29889

Next is the “Neitchhing” [Neicheng, Inner City], where there were private gardens and lakes, temples and altars, alongside bureaucratic offices and storehouses (fig. 4).

Fig. 4, Detail, Inner City, Map of the City of Beijing, MacLean Collection 29889

The final section of the index lists places in “Waitchhing” [Waicheng, Outer City], which remained sparsely populated in the early nineteenth century (fig. 5). The area featured fields, military barracks, and vegetable gardens along its perimeter, with the Temple of Heaven situated at the southeastern border—a sacred site where emperors conducted annual ceremonies to pray for a bountiful harvest.

Fig. 5, Detail, Outer City, Map of the City of Beijing, MacLean Collection 29889

While we do not know exactly who drew and etched this map onto copperplate, it was likely produced in Saint Petersburg following Bichurin's return in the 1820s. However, the map employs some visual techniques found in Chinese manuscript and woodblock-printed city maps dating back centuries. Some of these techniques include variable perspectives and orientation, as well as a combination of pictorial and abstract elements.

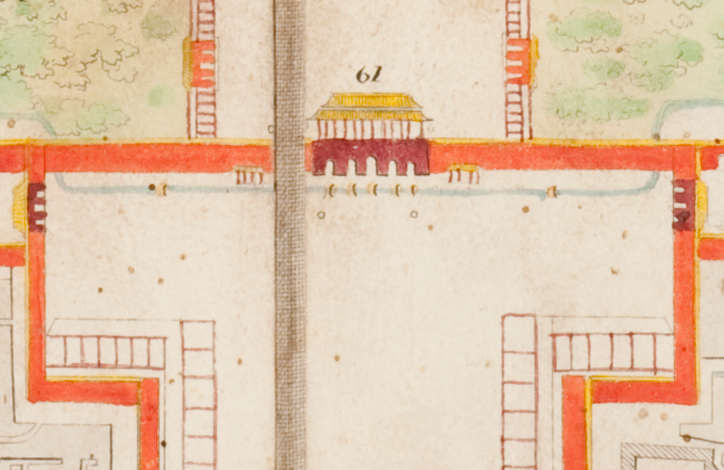

For example, when looking at Map of the City of Beijing, readers are offered two different ways of seeing the city: it presents Beijing from bird's eye view, showing the overall layout while also depicting important sites in elevation view as if observed from ground level (fig. 6). This is particularly noticeable in the city center, in which we see the sequence of gates, halls, corridors, and passageways leading into the Forbidden City.

Fig. 6, Detail, Pathway leading into the Forbidden City, Map of the City of Beijing, MacLean Collection 29889

Tiananmen's façade is rendered with precision—it has nine bays, five arched gateways, and a double-eaved, hip-gabled golden roof. Just below the gate, five small golden dots, each accented with a dark curl, span across a thin blue line (fig. 7). These markers represent the five ceremonial bridges crossing the Jinshui moat.

Fig. 7, Detail, Tiananmen, Map of the City of Beijing, MacLean Collection 29889

Just beyond the walls of the Forbidden City rises the Baita [White Pagoda], perched atop Jade Flower Island in Beihai Park, commanding a panoramic view of the entire city (fig. 8). The map depicts the pagoda's base, dome, and spire, as well as its placement amid halls, bridges, and interconnected pavilions, further demonstrating the map's attention to architectural detail.

Fig. 8, Detail, Jade Flower Island in Beihai Park, Map of the City of Beijing, MacLean Collection 29889

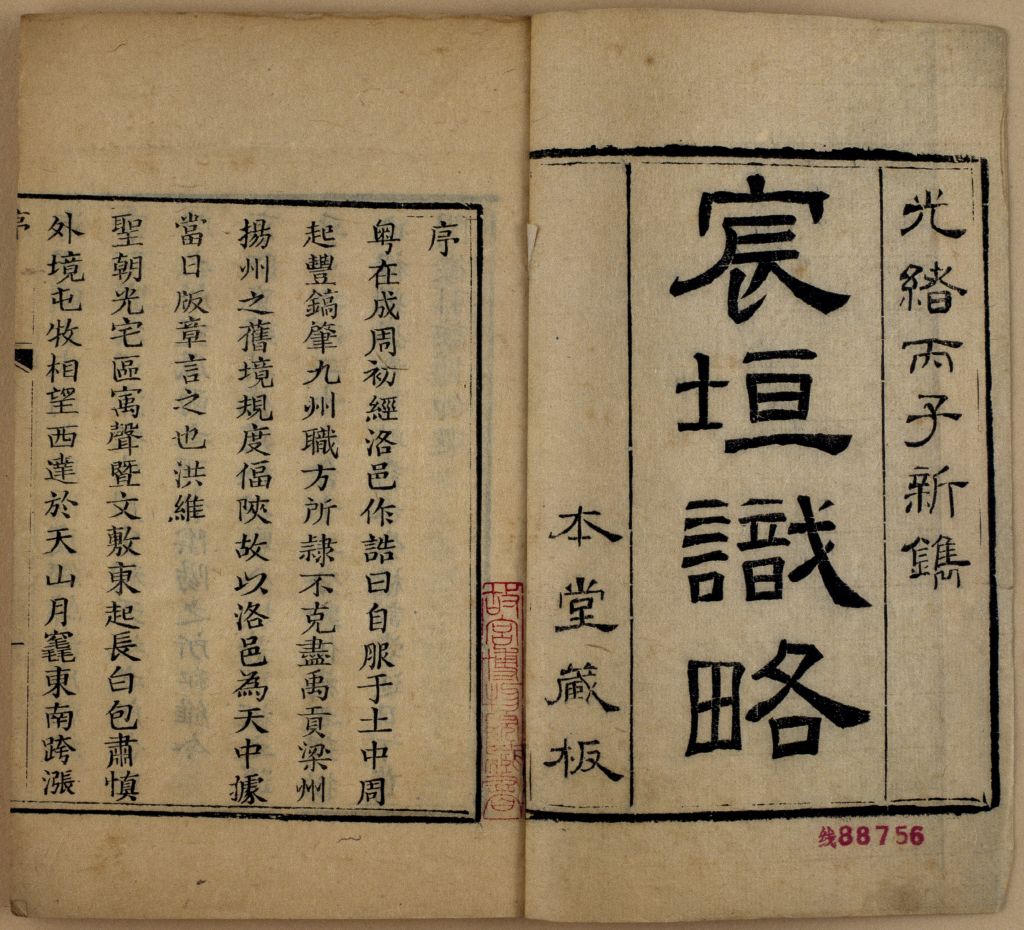

Map of the City of Beijing first appeared not as a standalone map but as an appendix to a book Bichurin published in Saint Petersburg in 1829. The book was Bichurin's translation of Sketches of the Imperial Enclosure [Chenyuan shilüe], a popular guidebook first published in 1788 (fig. 9). Its original author, Wu Changyuan, had combed through books and gazetteers to compile information about Beijing's history, design, architecture, infrastructure, and landmarks. He was also a longtime resident of the city and supplemented his findings with poems, anecdotes, as well as his observations and amendments. The result was a comprehensive but portable work consisting of sixteen bound volumes, or juan.

Fig. 9, Sketches of the Imperial Enclosure [Chenyuan shilüe],

Wu Changyuan [active 18th century], dated 1788, woodblock printed book,

ink on paper, 12.8 × 9cm, Palace Museum, Beijing

https://www.dpm.org.cn/ancient/yuanmingqing/149509.html

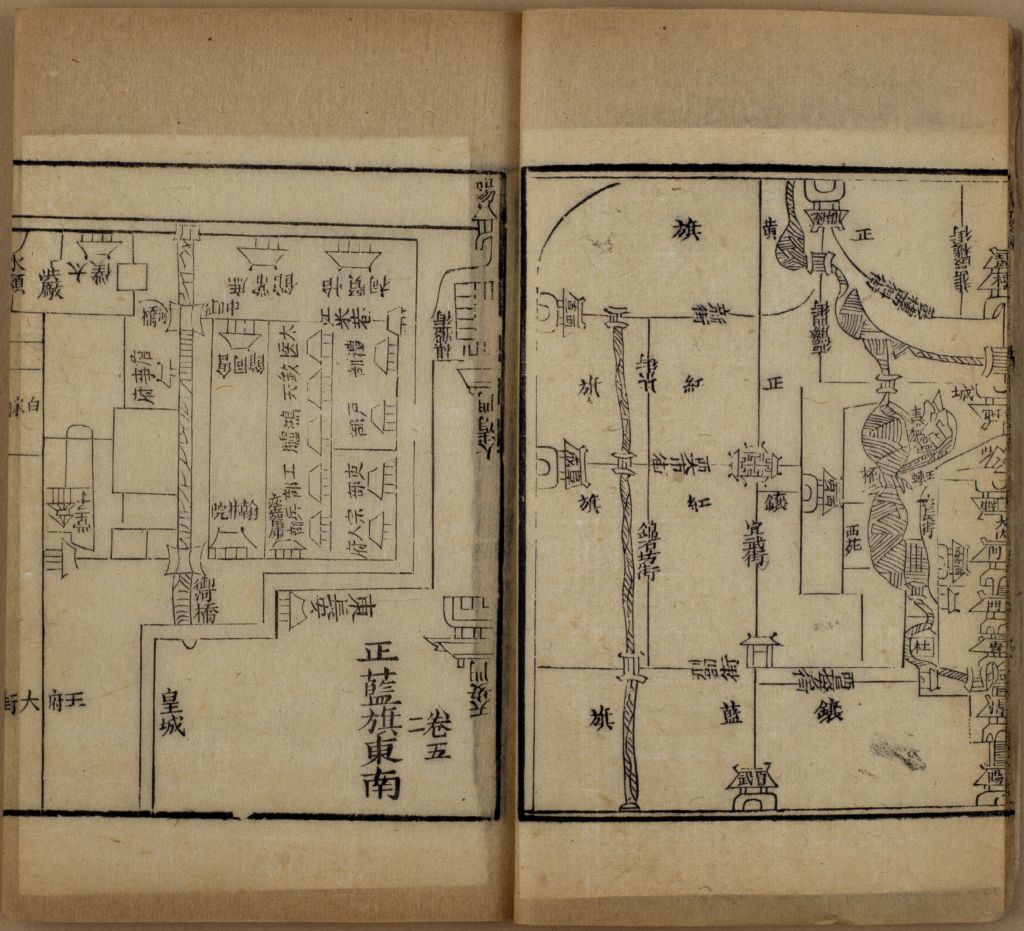

Eighteen maps are interspersed throughout the juan, offering a different view of Beijing (fig. 10). Compared to Map of the City of Beijing, these maps, while smaller and printed on woodblock, offer close-up views of the city. They show, for example, where individual Banner units lived, the Western Gardens, and the city's extensive moat and canal system.

Fig. 10, Detail, Map from juan 5 showing the Plain Blue Banner community located adjacent to Tiananmen, Sketches of the Imperial Enclosure, Palace Museum, Beijing

Bichurin translated Wu's text and added interpretations and insights. French, German, and English translations followed soon after. In the preface to the book's English edition, Bichurin acknowledges, “The description of the city and accompanying plan is not my own work. The testimony of an inhabitant (or native) of the country deserves indisputably much more credit than that of a foreigner.”

Continue →