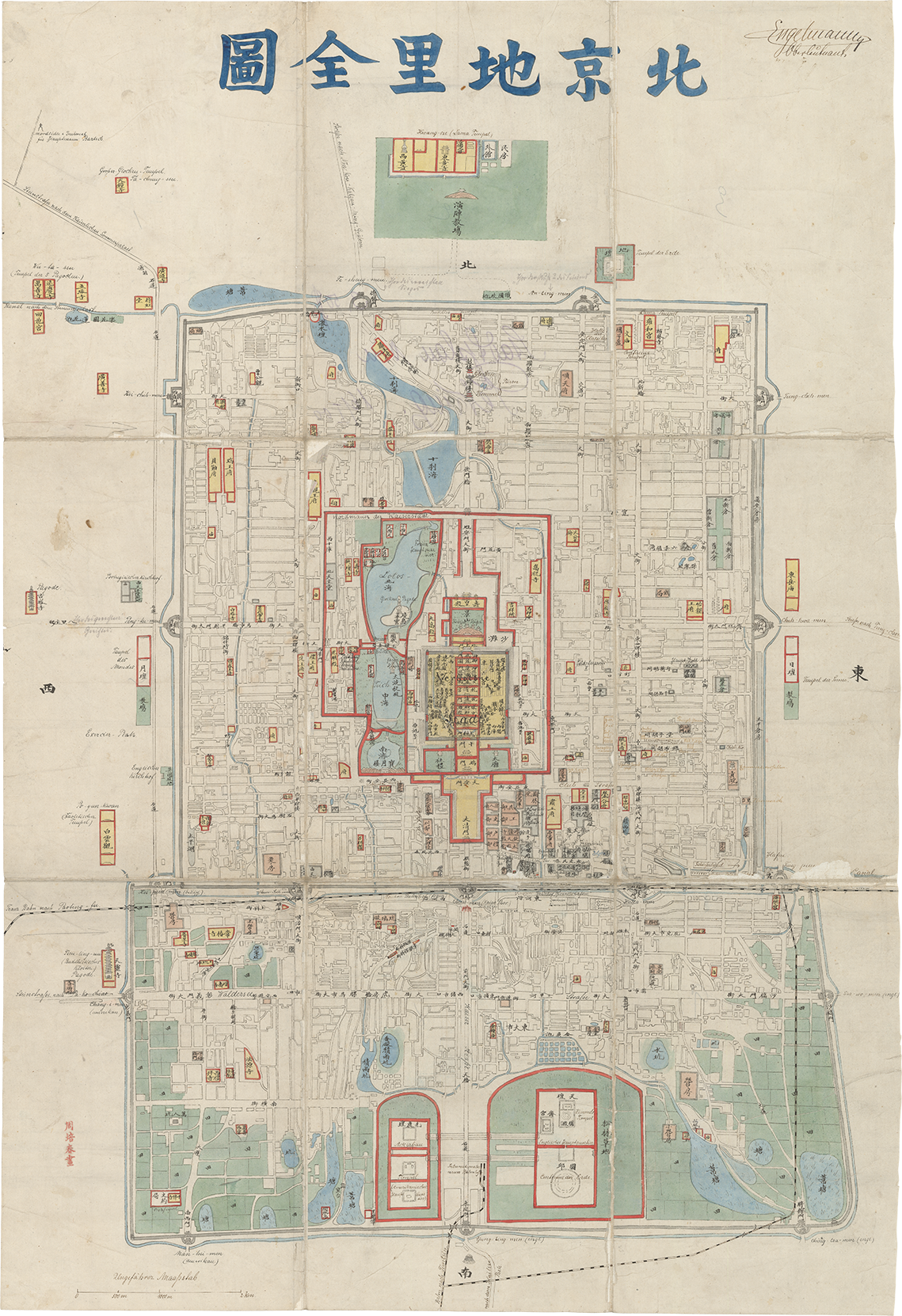

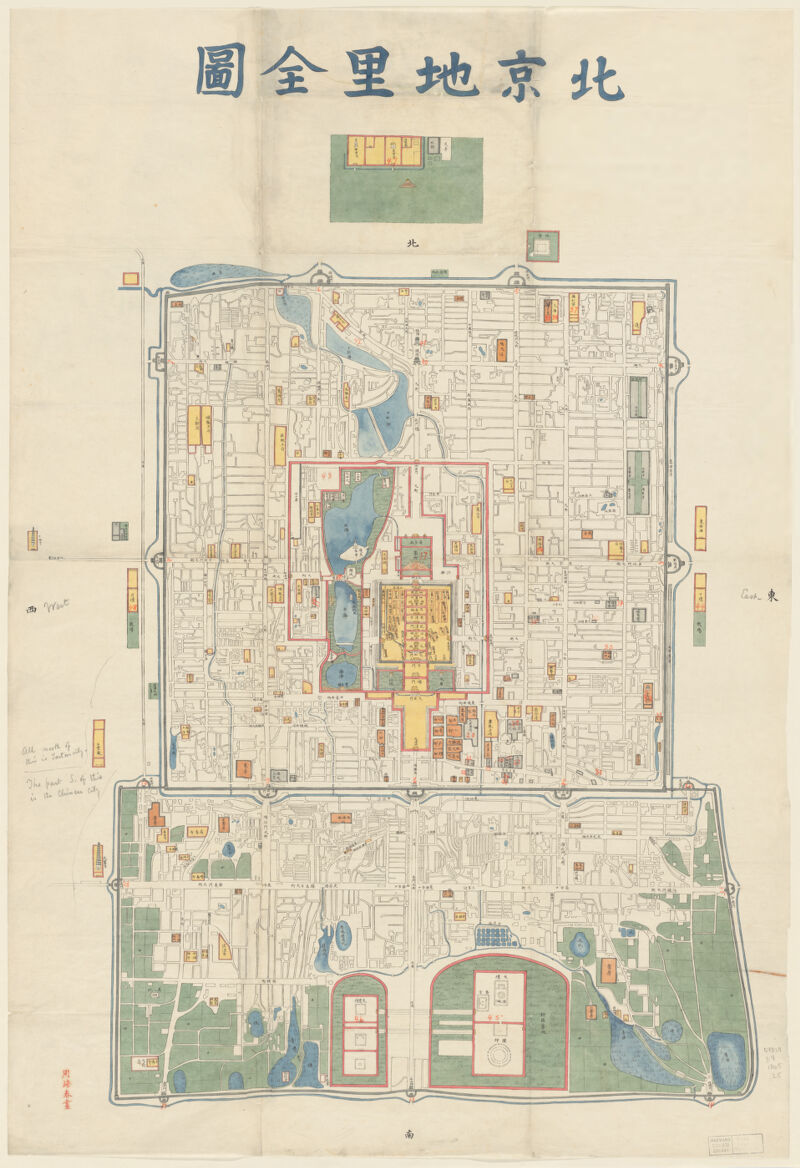

Copies of Map of the City of Beijing are rare. However, its likeness can be seen in a later map also housed in the MacLean. This Complete Map of Beijing [Beijing dili quantu], employs comparable visual elements—similar colors, shapes, and variable perspectives—but is hand-painted (fig. 11a). It bears the stamp of the Chinese artist and illustrator Zhou Peichun (active 1880-1910), whose workshop was located just outside the Imperial City walls (fig. 11b). The workshop specialized not in maps, but in trade paintings, a genre of images produced by Chinese artists and artisans for the foreign market. These paintings showed Chinese people, life, and customs in a variety of forms, ranging from small albums to large scrolls. While historical details about Zhou and his workshop remain sparse, the hundreds of trade paintings attributed to him in museums and special collections worldwide suggest production by a coordinated team of skilled artisans rather than a single creator.

Fig. 11b, Detail, Zhou Peichun stamp (lower left), Complete Map of Beijing, MacLean Collection 33320

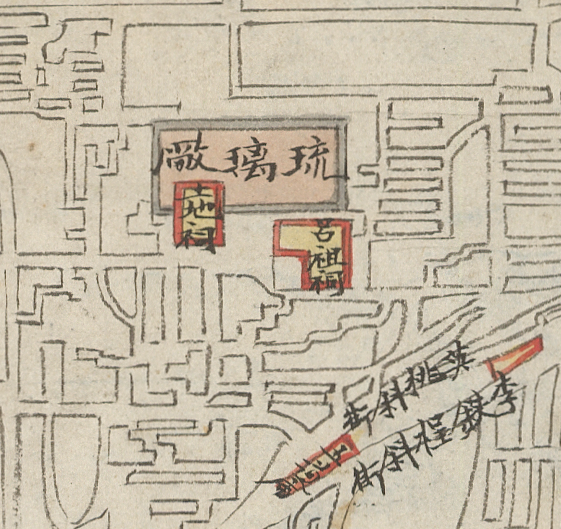

Though visually similar, Zhou's map is not a copy of its predecessor. Written entirely in Chinese, it contains more than double the toponyms. This is particularly visible in the Outer City, where commoners—like the artisans—may have resided. Ordinary places like factories, kilns, barracks, passageways, and intersections that only residents would recognize are also marked (fig. 12). In other words, through the painstaking process of re-drawing the map, the artisans adapted it to reflect their understanding of Beijing.

Fig. 12, Detail, ceramic glaze factory in Outer City, Complete Map of Beijing, MacLean Collection 33320

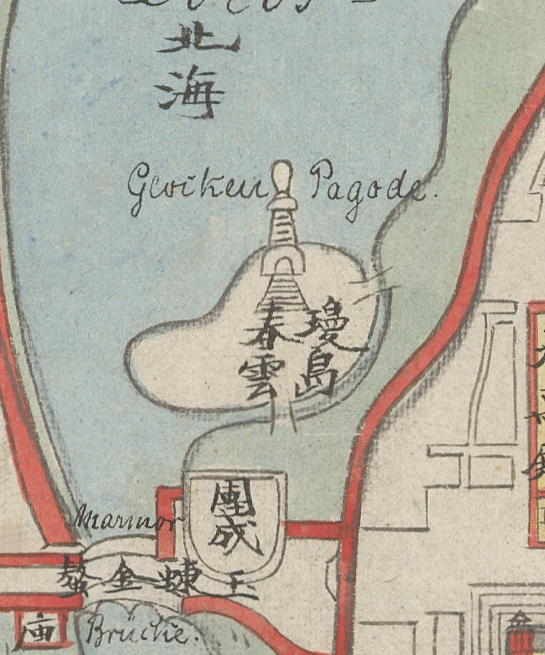

The map underwent other kinds of changes. The index and scale bar were eliminated, but cardinal directions, indicated by single characters on the corresponding edge, were added. Chinese maps would not adopt uniform scale and orientation as standard practice until the early twentieth century. Pictorial elements were also simplified throughout—Tiananmen was reduced to a gate icon and Jade Flower Island was stripped of the details found on Bichurin's map—likely to expedite production and accommodate place names (fig. 13).

Fig. 13, Detail, Jade Flower Island in Beihai Park, Complete Map of Beijing, MacLean Collection 33320

It is unclear how many of these maps Zhou's workshop produced. A handful of similar maps exist in various collections, including Wattis Fine Art in Hong Kong and the British Library, that bear either the title Beijing dili quantu, Beijing quantu, or Jingshi quantu, but not all bear Zhou's name stamp. One version housed at the Library of Congress is signed 北京學生李明智畫 [“Drawn by Beijing student Li Mingzhi”] and dates between 1861 and 1887. Another version remains unsigned and unfinished, with most of its color and toponyms absent. This suggests that the maps were created from a standardized template in an assembly line process.

Two copies stand out from this group of maps. They both belonged to foreigners who adapted them to suit their personal needs and interests. The first, now in the Harvard Map Collection, belonged to someone who was likely a customs agent or one of their family members (fig. 14a). They added quick handwritten notes directly onto the map with basic information like “the square in the middle of all is the Palace—(forbidden to foreigners).”

Fig. 14a, Complete Map of Beijing [Beijing dili quantu], Zhou Peichun (active 1880-1910), manuscript sheet map, 80 × 62cm, Harvard Map Collection, G7824.B4 1865 .Z5 vf

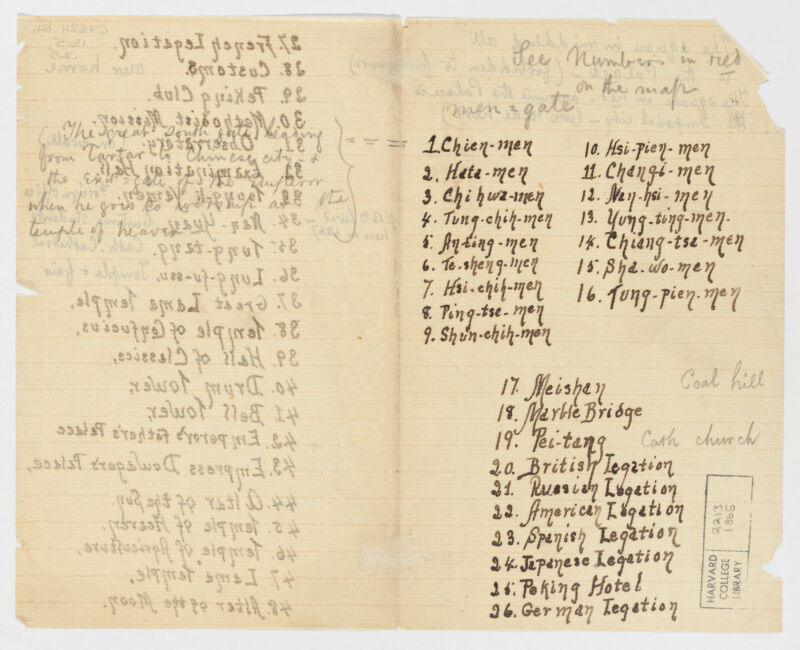

They also created a simple index on a separate sheet of notebook paper with additional explanations (fig. 14b). Some of these notes are personal, such as “EBD lived here in 1867” and “our home” next to the customs house. In this way, the map became a souvenir that the owner could later show to curious friends and family members as a way to reminisce about their time in a faraway land.

Fig. 14b, Accompanying index to Complete Map of Beijing [Beijing dili quantu], Harvard Map Collection, G7824.B4 1865 .Z5 vf

The second map, now part of the MacLean Collection (fig. 11a), belonged to a German lieutenant named Otto Engelmann, whose signature can be found on the top right corner (fig. 15). He was among the 50,000 troops deployed to northern China in the summer of 1900 to join the Eight Nation Alliance, which was tasked with quelling the Boxer Rebellion. The Boxers (known by the Chinese as the Yihetuan, or the “Militia United in Righteousness”) sought to restore cosmic order over their drought-ridden lands by purging China of foreign presence and influence. They killed foreigners and Chinese Christians, ripped up railways, and cut telegraph lines. That summer, they laid siege on the Foreign Legations, located just outside the Imperial City's walls, where missionaries, diplomats, their families, and Chinese Christians had been seeking refuge.

Fig. 15, Detail, Otto Engelmann's signature, Complete Map of Beijing, MacLean Collection 33320

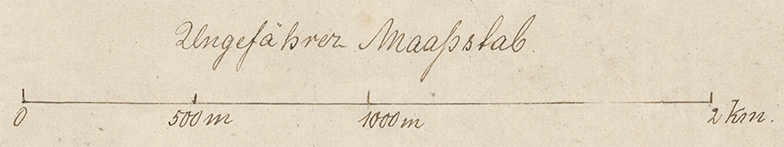

Engelmann made numerous additions to the map, including a scale bar with the metric system, though he could only describe it as “approximate” (fig. 16)

Fig. 16, Detail, Scale bar, Complete Map of Beijing, MacLean Collection 33320

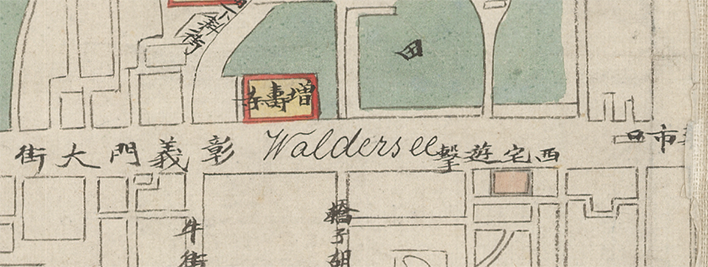

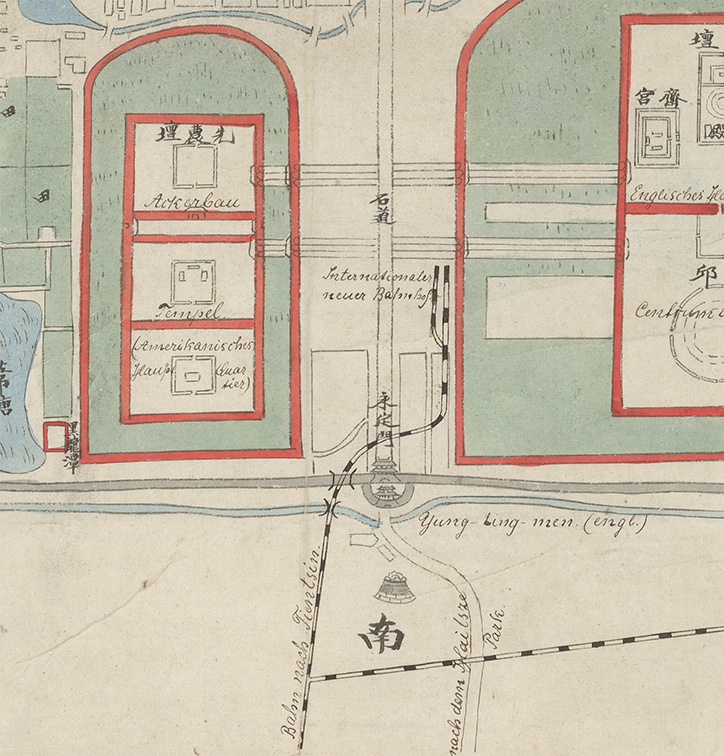

Many toponyms were translated from Chinese to German, while others were renamed entirely. A main thoroughfare in the Outer City became “Walderseestraße,” after the esteemed German field marshal Alfred von Waldersee who led the Alliance (fig. 17). Engelmann also showed how key sites were occupied and repurposed during and after the battle. American and British troops were headquartered in the complex of the Temple of Heaven, while a field hospital was established just outside the eastern wall of the Imperial City.

Fig. 17, Detail, Waldseestraße in the Outer City, Complete Map of Beijing, MacLean Collection 33320

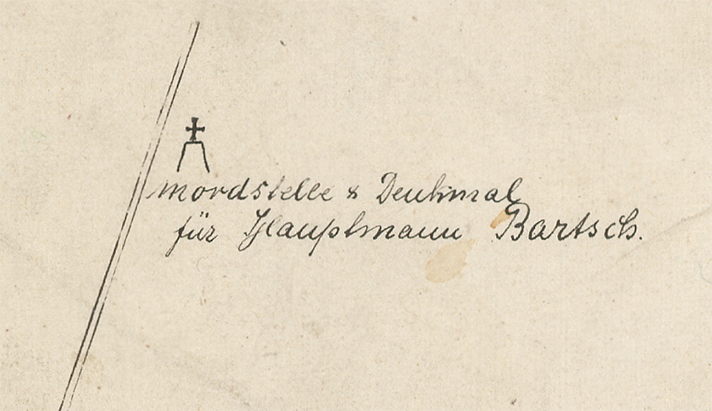

Other annotations were more personal. Along a newly drawn road leading to the Summer Palace in the northwest suburbs of Beijing was the memorial for one of Engelmann's superiors, Captain Bartsch, who was claimed to have been murdered by a Boxer (fig. 18).

Fig. 18, Detail, Memorial to Captain Bartsch outside of Beijing, Complete Map of Beijing, MacLean Collection 33320

A notable addition that Engelmann made was a dotted line that cut through the Outer City, which represented a burgeoning network of railways that connected Beijing to other cities in the northern provinces. The Boxers had destroyed railway tracks and set fire to stations, severely disrupting the network. In August 1900, after the battle had subsided, military engineers of the expeditionary forces breached two portions of the city's outer walls to extend an existing line and build two new stations. (fig. 19) This was a highly symbolic event in the history of modern Beijing. Railway construction had been a fraught political and social issue for the Qing. The destruction of a section of the iconic walls, captured in numerous photographs, seemed to portend the demise of the Qing empire a decade later. Engelmann's map—itself a product of transculturation and adaptation—bore witness to this key moment in modern Sino-foreign relations.

Fig. 19, Detail, Railway added by Englemann, Complete Map of Beijing, MacLean Collection 33320

Continue →