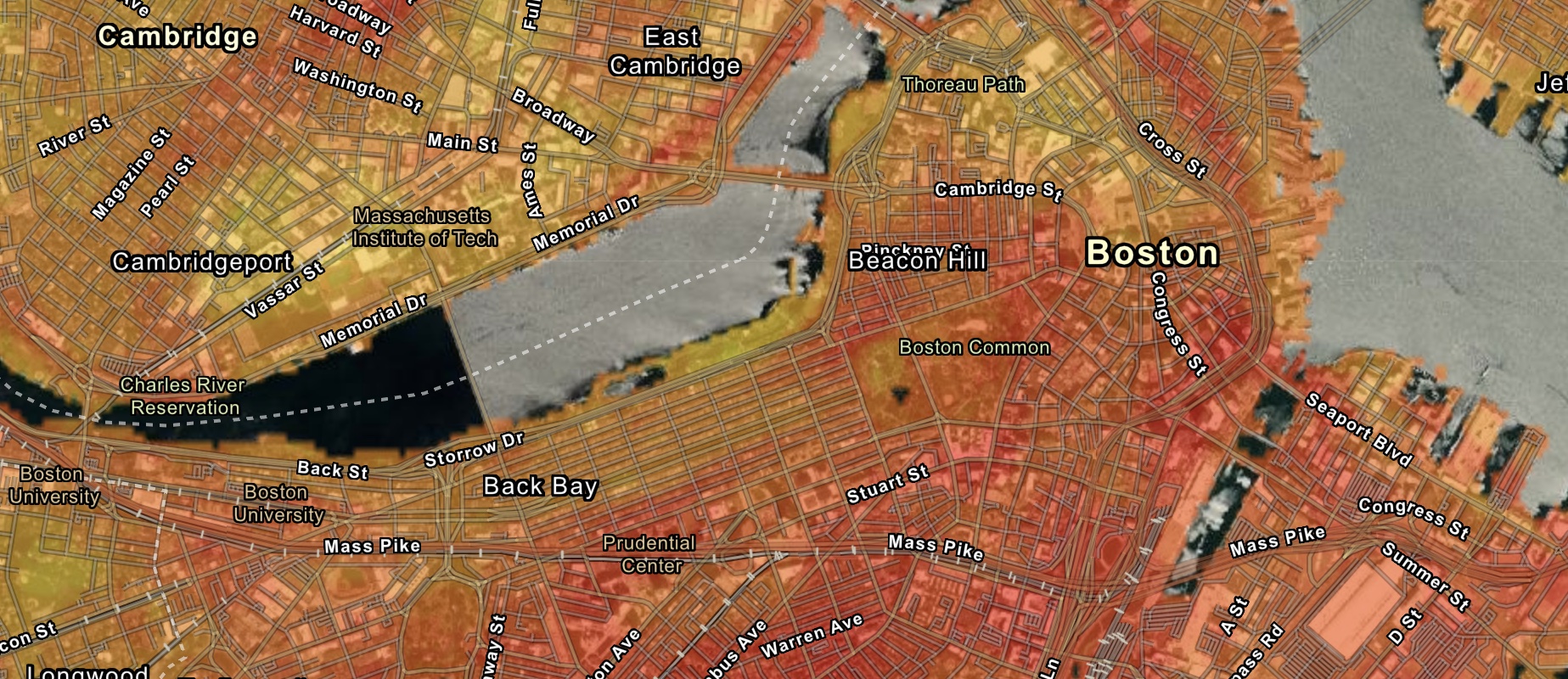

The word “marginalization” is not just a metaphor for social exclusion. The geographic margins of power and wealth are also where we are likely to find both the most environmentally damaged landscapes, as well as the communities that have suffered the most from historic systems of injustice. Environmental hazards often accumulate over decades, or even centuries, and this leads to reinforcing cycles of marginalization. Certain geographic features may make a place attractive to dirty industries, and these legacies remain in the landscape even after the industries themselves have departed. Therefore, when we look at maps of income, race, or immigration today, it’s often possible to see the patterns of long-vanished decisions about land use.

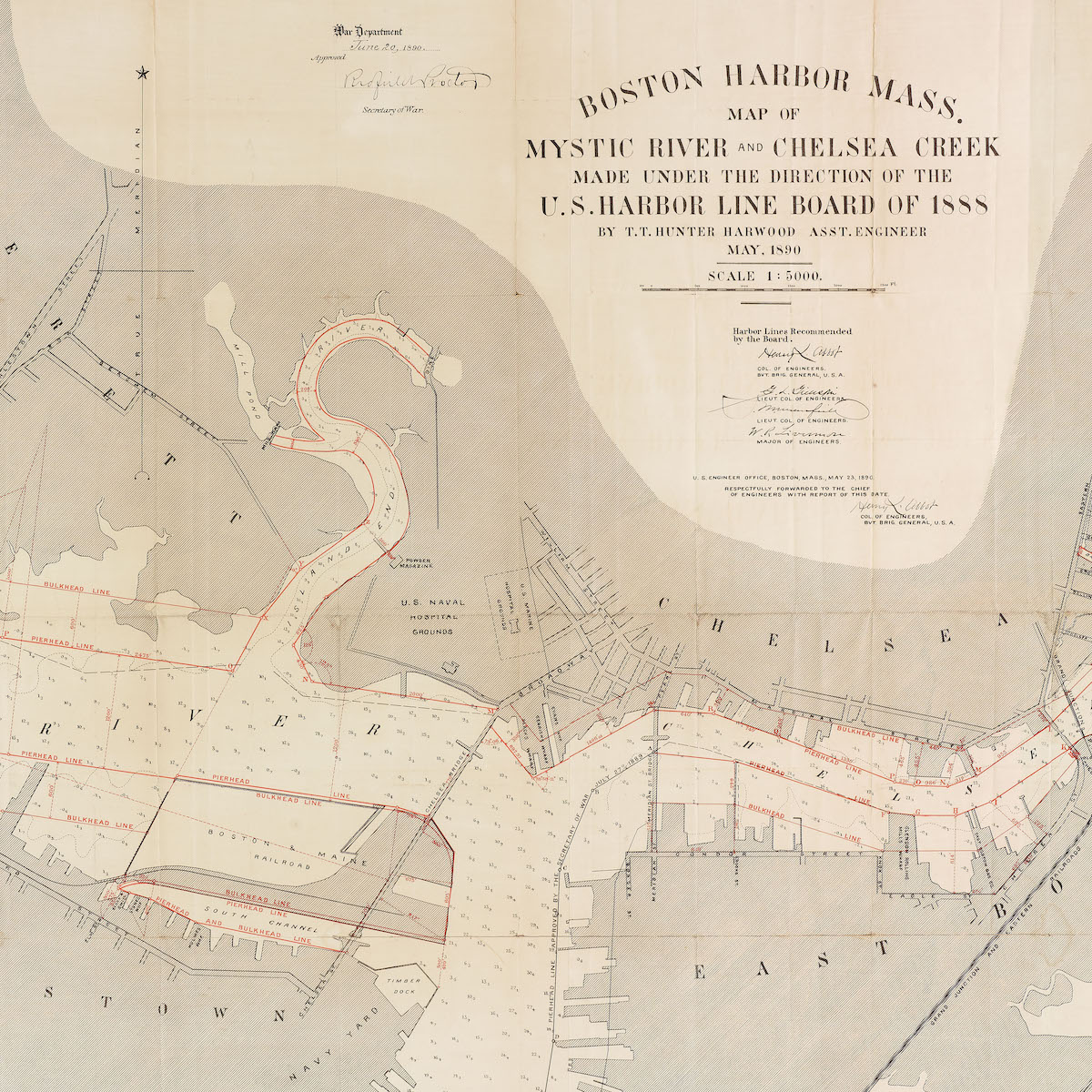

Boston Harbor, Mass.: Map of Mystic River and Chelsea Creek

U.S. Harbor Line Board of 1888; Boston Harbor Line Board; Massachusetts Board of Harbor and Land Commissioners

1890

State Library of Massachusetts

In April 1908, Chelsea was devastated by an enormous fire that tore through the city, including the oil tanks along the Mystic River, as seen in this postcard from the Chelsea Public Library’s collections. The air pollution from this event was one of the worst toxic disasters in Massachusetts history.

The Mystic River and Chelsea Creek have long been the location of some of Boston’s most polluted landscapes. This 1890 map of the area, created by military engineers who were appointed to manage the harbor’s navigation, shows how early efforts at environmental controls were primarily directed at facilitating the demands of a working waterfront. Shallow tidal flats and shifting channels presented a challenge for waterborne freight, so engineers and surveyors (the predecessors to today’s environmental regulators) drew lines like the red ones on this map to delineate shipping channels. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, this area—with plentiful cheap, flat marshland located at the meeting-point of marine and rail traffic networks—became crowded with shipping yards, oil tanks, and chemical plants. The Island End River, making an S shape near the center of this map, was almost completely filled, and a coal tar plant left the remaining stretch contaminated with toxins called PAHs.

Map of the City of Chelsea: from Actual Surveys 1867

J. Mayer & Co.

1867

Leventhal Map & Education Center

Just north of Boston, Chelsea is today both one of the poorest municipalities in Massachusetts as well as one of its most diverse, with a large immigrant population. Although Chelsea’s population was very different in 1867, this map shows how some of the features of this intertwined system of environmental and social marginalization began to take shape. Railroads running through the city served largely to speed freight from coastline terminals onward to other destinations; later, Chelsea found itself surrounded and yet isolated by transit and highway networks. Former industrial yards became storage depots for road salt and jet fuel. Modern studies have found that Chelsea is one of the places in the state most “overexposed” to environmental hazards. For these reasons, the city has become the site of energetic political and activist movements for environmental justice.

Greenroots

Advocating for Comprehensive Community Welfare

How can environmentally overburdened communities command attention in order to affect change? Aside from dealing with the immediate health threats of hazardous chemicals and other nuisances there is the more complex question of how the community became overburdened in the first place. Greenroots, which grew out of grassroots community organizing in Chelsea over 20 years ago, asks these questions as it works towards justice. This organization today encompasses a staff with broad expertise who focus on the immediate needs of their surrounding communities, from a comprehensive COVID response plan to helping organize and file multiple lawsuits against the utility Eversource to defeat the construction of an electrical substation in East Boston.

“When we talk about the official definition of environmental justice, particularly from government, it emphasizes equity or equality as if we’re all in the same boat. But there is deep inequality. So we start from that point and recognize that some communities are so far overburdened and behind the curve in terms of resources. That’s where you have to begin: recognizing that history. Green Roots focuses on a variety of things that overlap in a community…and promoting the greater welfare of the community.” —Marcos Luna, Board Member of Greenroots

Learn more

“People talk a lot about communities of color, immigrant communities, low-income communities being, you know, hit first and worst”

Read more about the fight for environmental justice in places like Chelsea in this 2017 WBUR article.