After the Civil War, particular attention was paid to tending to public welfare. The urban atlases document the growing density of charities, hospitals, relief societies, and human services, putting the social element of the busy city directly onto the map.

ASSESSING THE GREAT FIRE OF 1872

Probably the best-known publisher of urban atlases used for rating fire insurance was Daniel Sanborn of Somerville, who started creating maps of this kind in 1866. Sanborn atlases featured a rich and evolving array of representational features, employing combinations of letters, colors, and lines to convey building materials, interior fixtures, and even window arrangements. All were relevant to assessing a building’s risk of catching fire and calculating insurance rates.

One of the symbols visible in this 1867 Sanborn plate shows the letters A through D , which classified warehouses according to their fire preparedness. “A” had multiple fire prevention measures while “D” had few, if any. The map shows the warehouses which were the tinderbox of Boston’s Great Fire. Spreading over 65 acres, the fire destroyed much of the waterfront downtown and growing financial district in 1872. This atlas shows many D-class warehouses in the area where the fire began, less than two decades before the disaster.

Insurance map of Boston, volume 1, plate 17

D. A. Sanborn

1867

Leventhal Map & Education Center

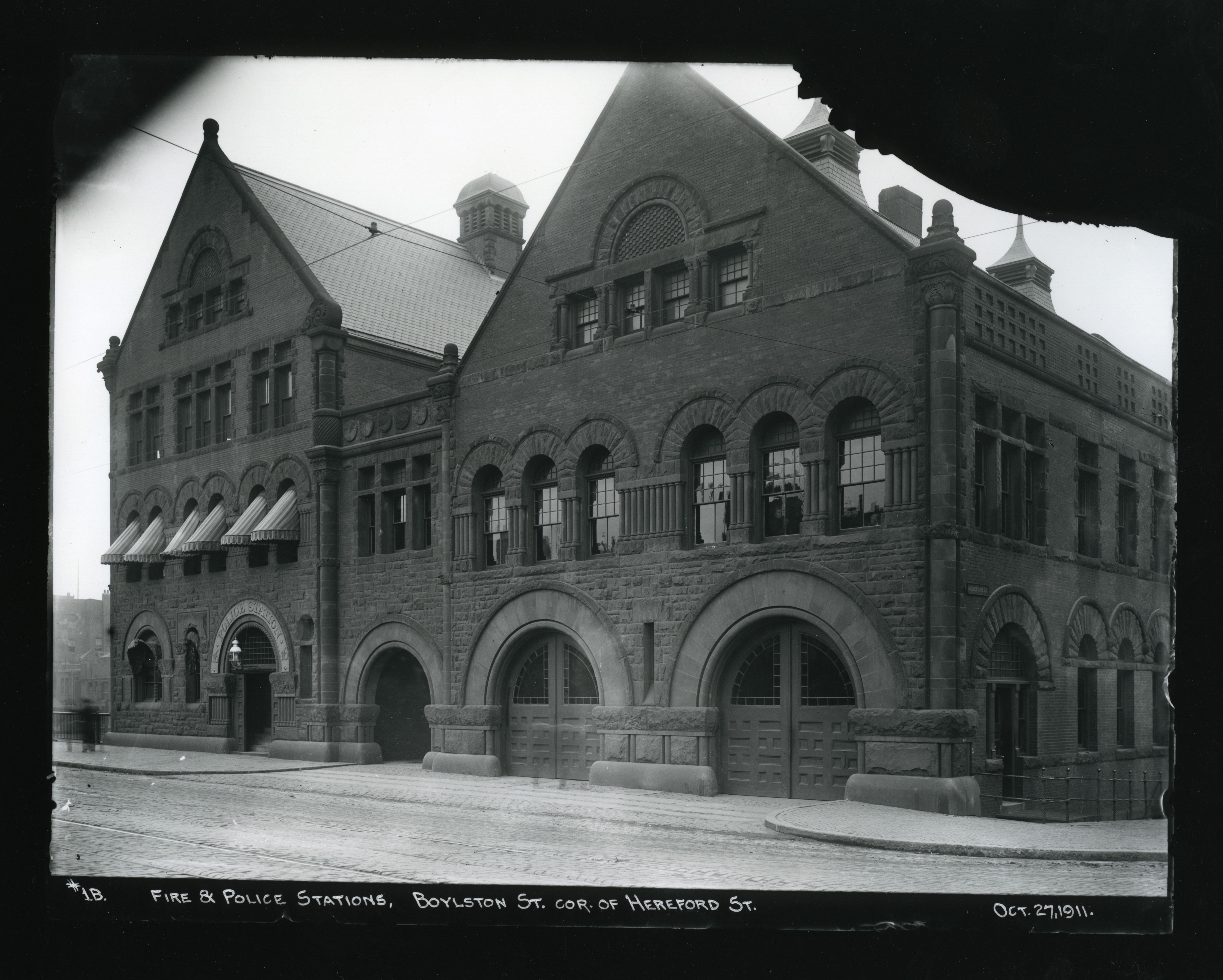

One consequence of the Great Fire of 1872 was the call for more fire departments closer to downtown, at the same time as the new Back Bay neighborhood was being built on filled land. This Bromley atlas from 1898 shows Engine 33 and Ladder 15, which still sit today in a Richardsonian Romanesque station not far from Copley Square.

Detail from Atlas of the city of Boston, Boston proper, plate 22

G.W. Bromley & Co.

1898

Leventhal Map & Education Center

Fire and Police Stations on the corner of Boylston Street and Hereford Street

Boston (Mass.). Transit Commission

1911

Boston City Archives

The Great Fire at Boston, November 9th and 10th, 1872

[ca. 1872]

Boston Public Library Arts Department

Corner of Milk & Kilby Streets

[ca. 1872]

Boston Public Library Arts Department

DISTANCE AND ISOLATION: RESPONDING TO SMALLPOX

The presence of smallpox hospitals in atlases well into the 1930s is a reminder of the physical presence of the disease in the city as well as the great effort spent to mitigate it. Smallpox was an ancient affliction, but by the late eighteenth century medical professionals had methods to prevent its spread. Yet smallpox outbreaks in the twentieth century still brought social upheaval, as people coped with the disease and the social dislocations that followed in the wake of death.

From 1901 to 1903, Boston experienced its last smallpox epidemic. While most urban outbreaks by the twentieth century involved the virus’s minor strain, Boston’s outbreak involved the more dangerous major strain. The city mandated that, in all but extreme cases, patients be placed in a hospital. The primary location was the Southampton Smallpox Hospital, shown here in the 1882 Hopkins atlas.

City atlas of Boston, Massachusetts, plate 14

G.M. Hopkins

1882

Leventhal Map & Education Center

A quarantine station on Gallops Island, visible in the (12 1899 map of Boston Harbor), received patients with milder cases.

Detail of Map of Boston Harbor

Geo. H. Walker & Co.

1899

Leventhal Map & Education Center

Atlas of the city of Boston, Roxbury, plate 39

G.W. Bromley & Co.

1931

Leventhal Map & Education Center

Both the 1882 Hopkins and the 1931 Bromley atlases show a parcel of land which was owned by the City of Boston and the site of a smallpox hospital. In 1882, the area was nearly surrounded by South Bay. The map shows the isolation of the hospital from urban streets: the parcel sits on a small U-shape, cradled between two tidal creeks.

In the 1931 atlas, the hospital has moved and faces the renamed Southampton Street, just east of its intersection with Massachusetts Avenue. The hospital’s structure, still wooden, implies a modern medical architecture with hallways separating larger volumes of space. Despite the growth of the area, it remained an industrial periphery, with a nearby gas utility and a freight yard.

This area of present-day Jamaica Plain on Canterbury Street shows another simple wooden structure where those inflicted with smallpox were transferred, if not always willingly. Rural places on the outskirts of the city were seen as ideal locations for convalescence. In 1896, the map shows how thinly populated this area once was, and the hospital’s proximity to the cemetery evokes a somberness not often expressed in maps.

Florida's Story

In 1918, Florida, her mother, and Maria Louisa Baldwin founded the League of Women for Community Service, and soon after purchased a building at 558 Massachusetts Avenue in the South End. Initially intended to support Black soldiers during World War I, the League went on to fill many civic roles, including housing Black female students attending Boston universities. (Coretta Scott lived in the building while dating Martin Luther King).

Charity work was a foundational focus of Black women’s clubs. Though socially removed from the struggles facing most Black Americans, relatively well educated and affluent women felt it was their responsibility to use their advantages to care for others. Florida wrote in the Woman’s Era about hosting a hospital fair followed by a “special effort for (St. Monica’s Home), for sick and destitute colored women and children” whose “receipts were more than sufficient to supply the Home with all of its fuel for the year.”

The clubs also expressed care for the community by denouncing and organizing against the violence and discrimination that Black Americans faced. Ida B. Wells, who worked alongside Florida and her mother in founding the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, was a powerful anti-lynching advocate. In this open letter responding to British reformer Laura Ormiston Chant’s opposition to a Unitarian church resolution denouncing lynching, Florida uses her voice to speak out against racist terrorism:

“In the interest of common humanity, in the interest of justice, for the good name of our country, we solemnly raise our voice against the horrible crimes of lynch law as practiced in the south, and we call upon Christians everywhere to do the same or be branded as sympathizers with the murderers.“

— Florida Ruffin Ridley, May 19, 1894 (from The Woman’s Era, June 1, 1894)