While the leafy ideal of public parks in the late nineteenth century expressed a desire for shared democratic spaces, the same rural aesthetic was also used to mark off elite residential neighborhoods. Frederick Law Olmsted was hired by William Aspinwall to create an initial design for a private development on a hill in Brookline, though the Aspinwall Land Company later turned to another landscape planner for the final layout. The curving streets, large lots, and deep setbacks for buildings became typical environmental designs for desirable areas. Developments like these also secured a specific kind of privileged environment through deed restrictions that limited what kinds of buildings or uses could be located here—and sometimes prohibited groups like Blacks, immigrants, or Jews, from owning residences. Racial deed restrictions, which appeared in many suburban developments, were not legally invalidated until 1948.

Plan of Land Owned by the Aspinwall Land Company on Aspinwall Hill in Brookline, Mass.

Aspinwall & Lincoln; Heliotype Printing Co.

1885

Leventhal Map & Education Center

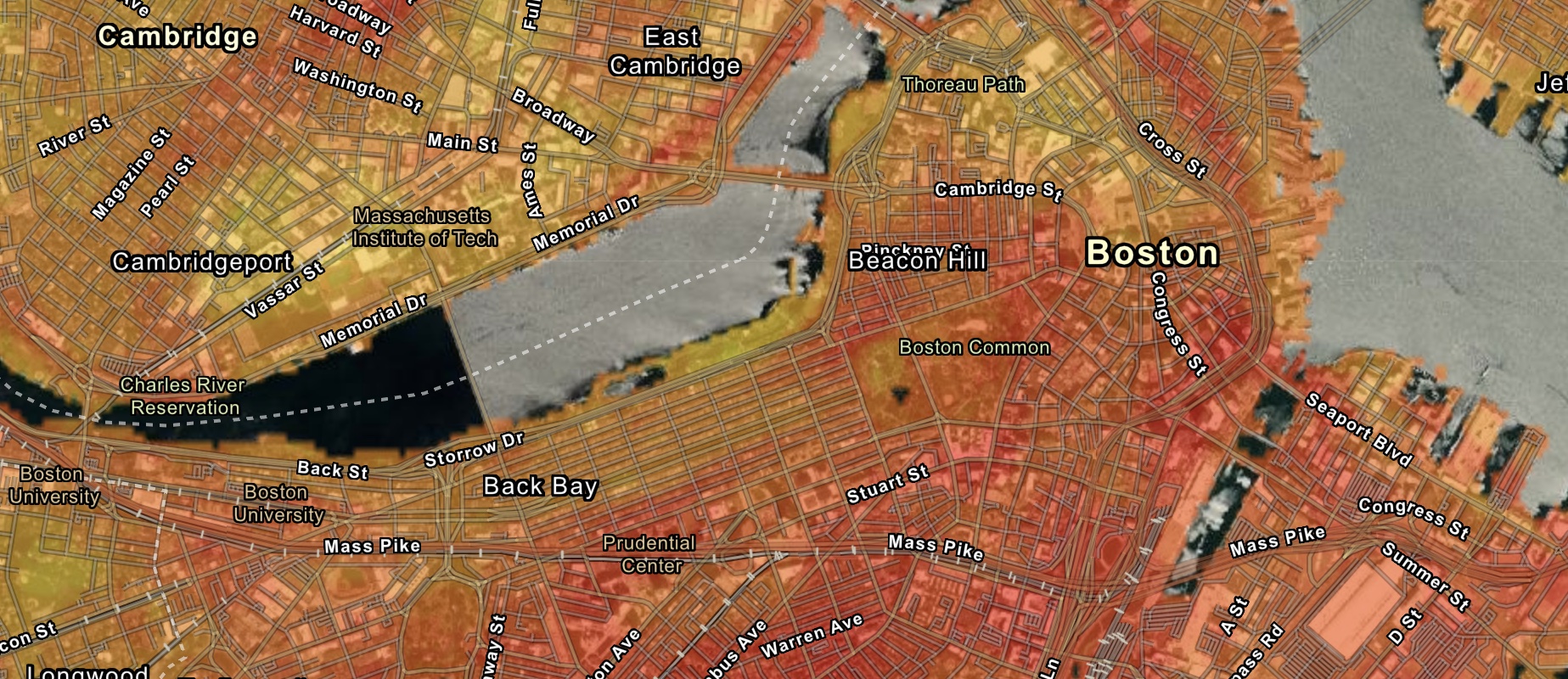

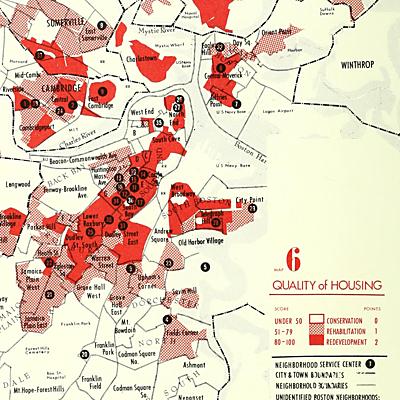

As older industrial cities like Boston began to go through painful economic realignments in the middle of the twentieth century, a gaping geographic divide began to open between privileged areas well-supplied with environmental amenities and other neighborhoods characterized by dilapidated housing and undesirable land uses. In this 1960 map created by the Boston Settlement Council, housing “quality” was evaluated on a 100 point scale, with solid red areas marking the worst conditions. The report’s other maps looked at factors like “social rank” and nonwhite populations to examine the geographic overlap between marginalization and neighborhood remediation. Reformers hoped that government-led redevelopment efforts could improve the environmental conditions of these areas and, by extension, raise the standard of living for the people living there.

Quality of Housing from Report of Long Term Planning Committee - Boston Settlement Council

United Community Services of Metropolitan Boston; Boston Settlement Council

1960

Boston Public Library

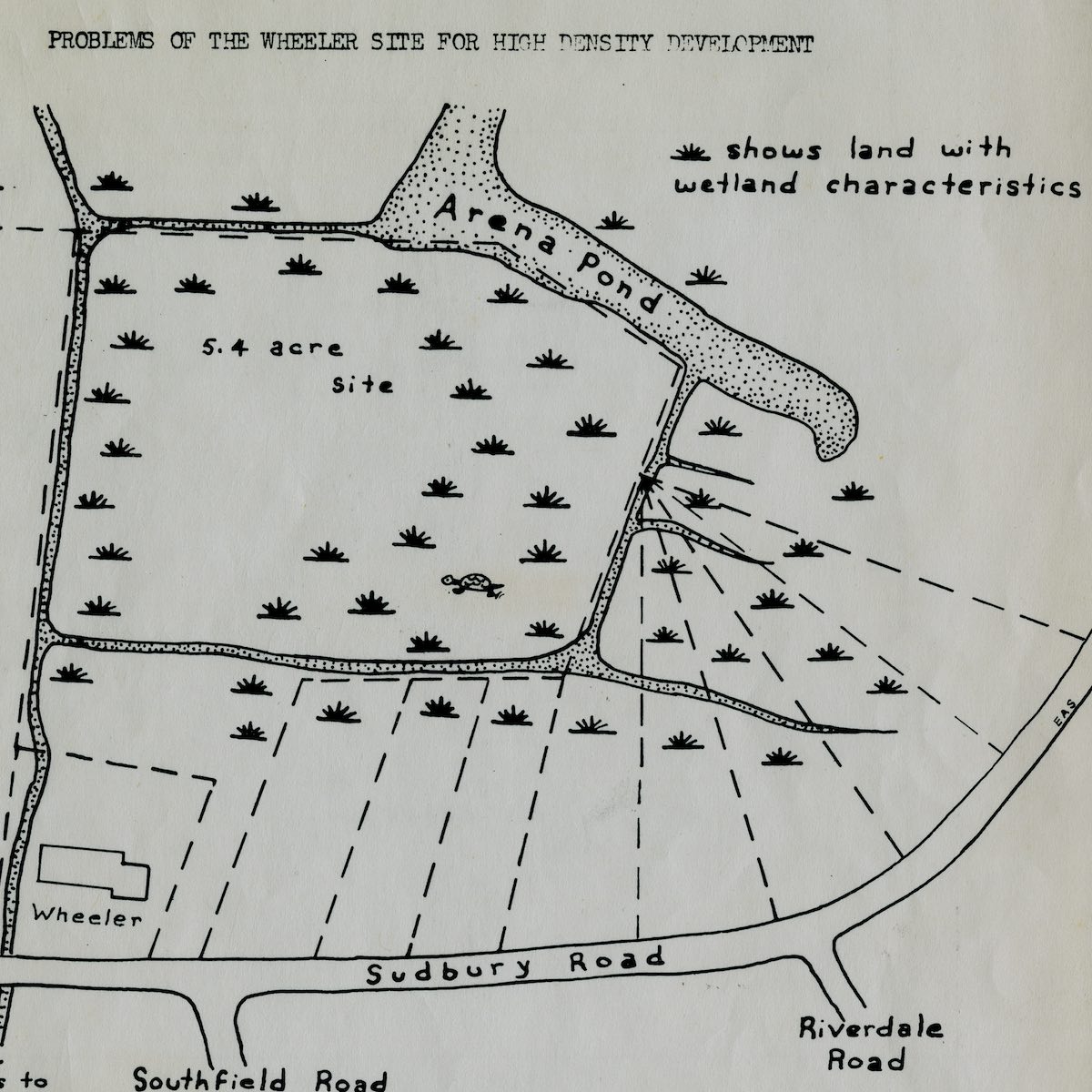

Problems of the Wheeler Site for High Density Development

Swamp Brook Preservation Association

1971

Concord Free Public Library

But as money and power began rapidly flowing out of the city into more desirable suburbs, many redevelopment efforts only made housing shortages more severe. By the time these inequalities had hardened, many suburbanites had come to feel that their own communities were under threat from overdevelopment. Thus, appeals to environmental conservation often served a second purpose—sometimes unintentionally but other times strategically—in order to prevent outsiders and “undesirable” populations from encroaching on suburban affluence. In the late 1960s in Concord, a group of advocates proposed a nonprofit affordable housing project on a site near the Sudbury River. Formed in opposition to the project, the Swamp Brook Preservation Association relied on environmental arguments about wetland protection to ultimately defeat the proposal. This map, produced by the Preservation Association, argues that “ecologically speaking, this land should not be filled.” While concerns about wetland habitat were certainly justified, without new housing Concord has remained for the most part economically and racially homogenous. Today, initiatives for suburban land preservation still cut uncomfortably across the need to create more equal and open communities.