Introduction

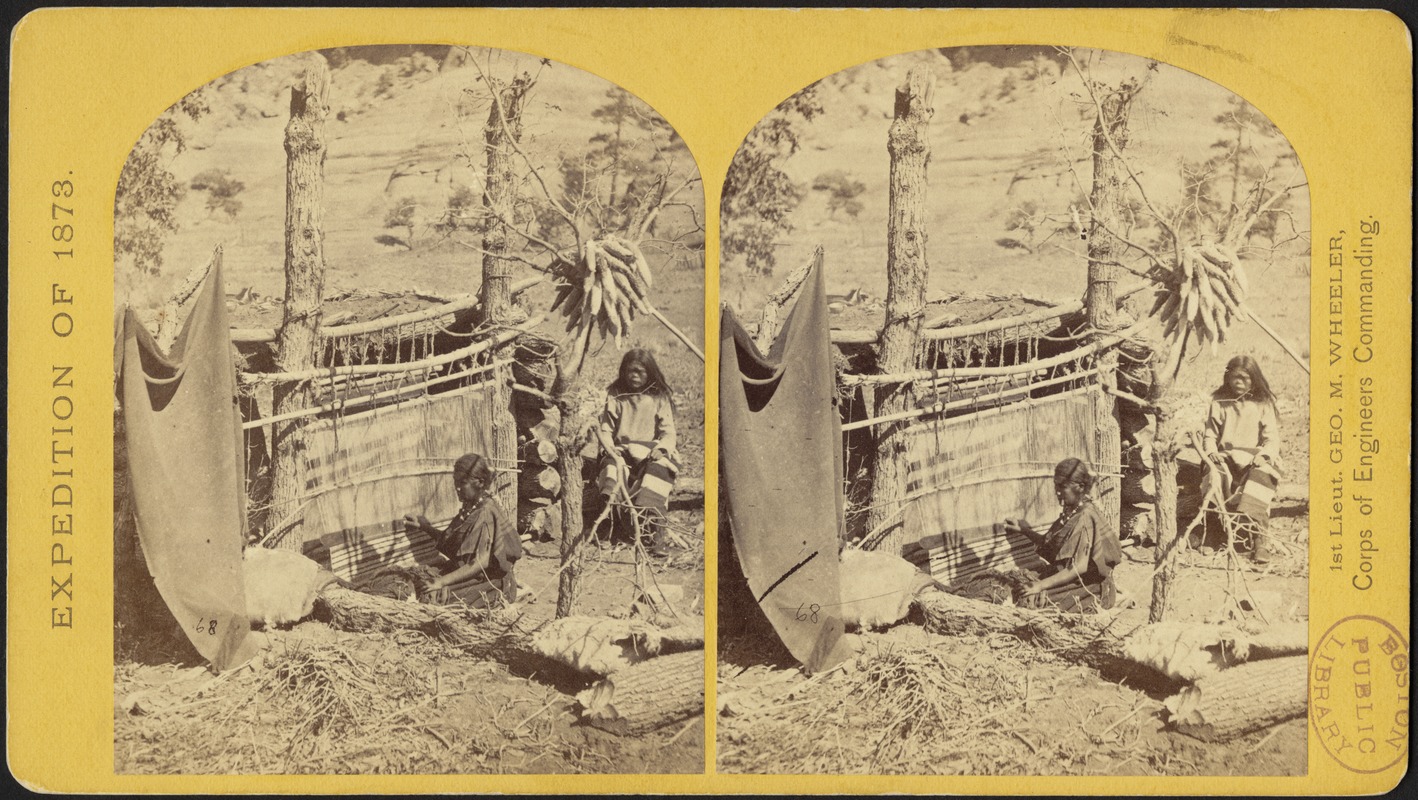

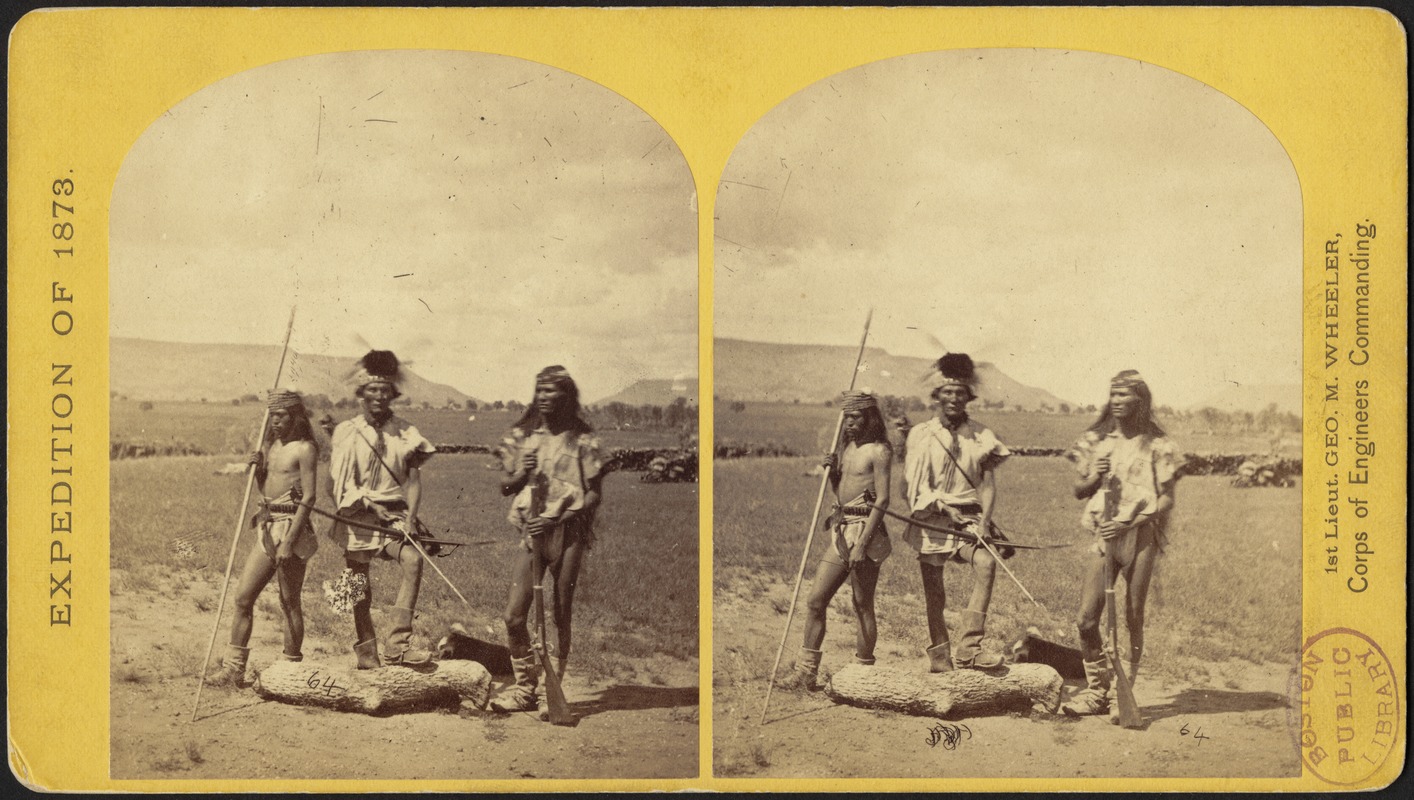

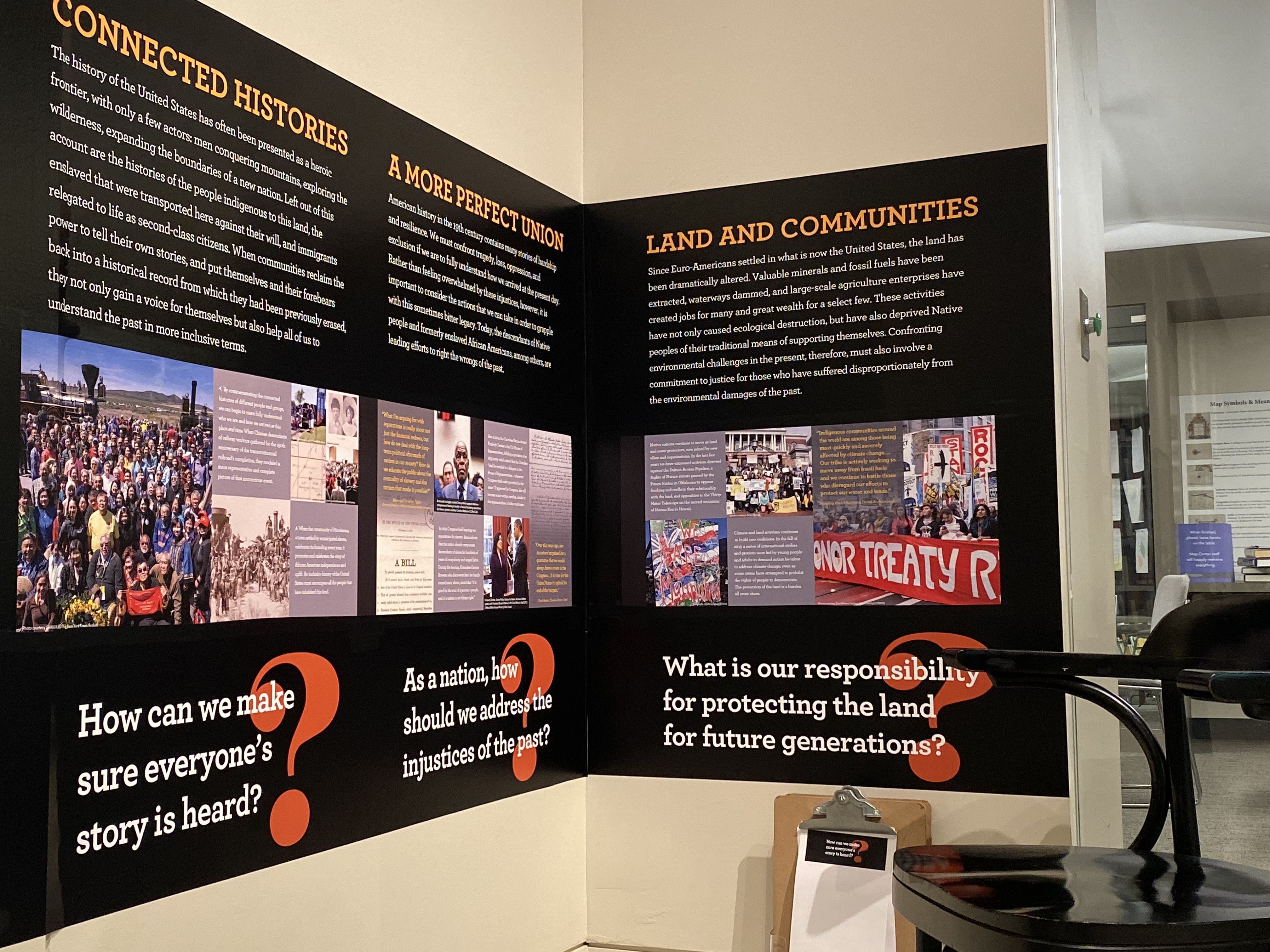

During the 19th century, the United States expanded dramatically westward. Immigrant settlers rapidly spread across the continent and transformed it, often through violent or deceptive means, from ancestral Native lands and borderlands teeming with diverse communities to landscapes that fueled the rise of industrialized cities. Historical maps, images and related objects tell the story of the sweeping changes made to the physical, cultural, and political landscape. Moving beyond the mythologized American frontier, this map exhibition explores the complexity of factors that shaped our country over the century.

The maps in this exhibition were created predominantly by Euro-American cartographers, and published by government agencies or commercial profit-seeking companies. They promote Euro-American culture and perpetuate certain interpretations of history. Considering the inherent power dynamics helps us understand that this was at the expense of other points of view – especially of indigenous peoples, those that were enslaved, and immigrant laborers, among many others. It is important to bear in mind how these documents reveal or conceal the ways people and communities were dispossessed, exploited, and annihilated. Unseen here but equally vital are stories of heroic resilience, resistance, and cultural preservation.

The Leventhal Map & Education Center stands on land that was once a water-based ecosystem that provided for the Massachusett people who lived in the Greater Boston area. We acknowledge these indigenous people, the devastating effects of settler colonialism on their communities, and their contemporary presence.

VIEWPOINT: The perspective of Native populations in the 19th century cannot be properly told in maps, because Native concepts about land are not two-dimensional, and qualifying ownership with a paper document was an imported European concept. During the rapid expansion of the United States, the idea of Native homeland, a multi-layered place giving life, sustenance, language, spiritual communion, and kinship, would change to a theory that land is preordained to be “improved” or “developed” for the purpose of commodification. This was a near universal change from Native land management systems that had sustained populations for millennia.

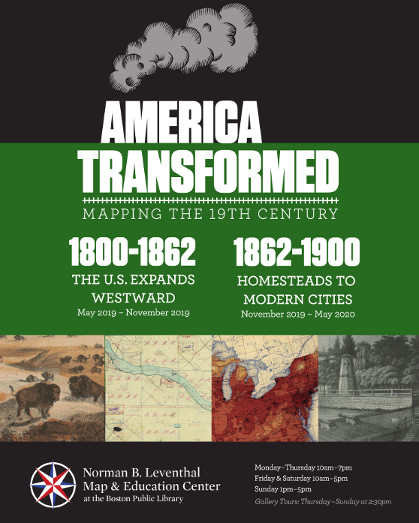

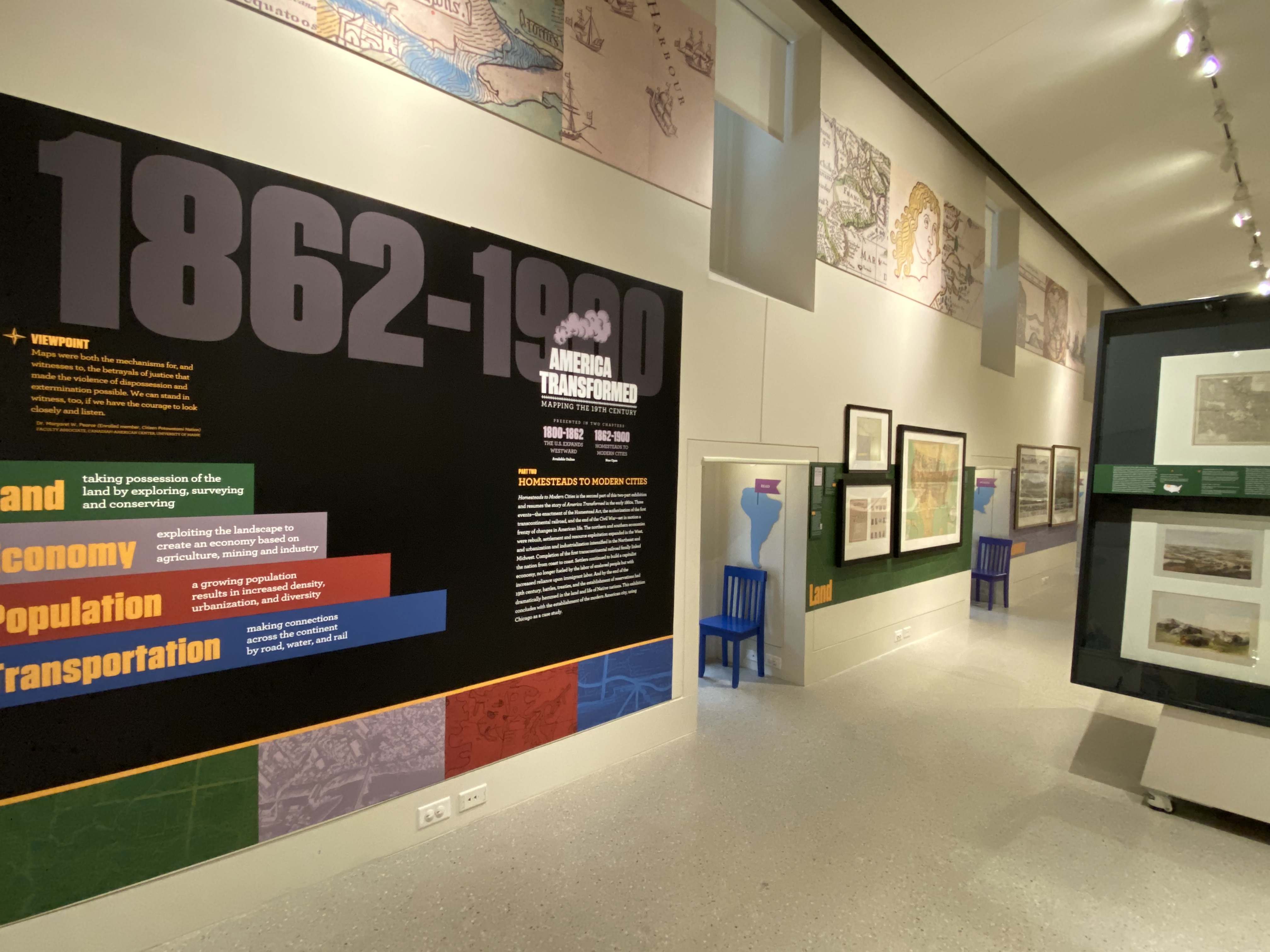

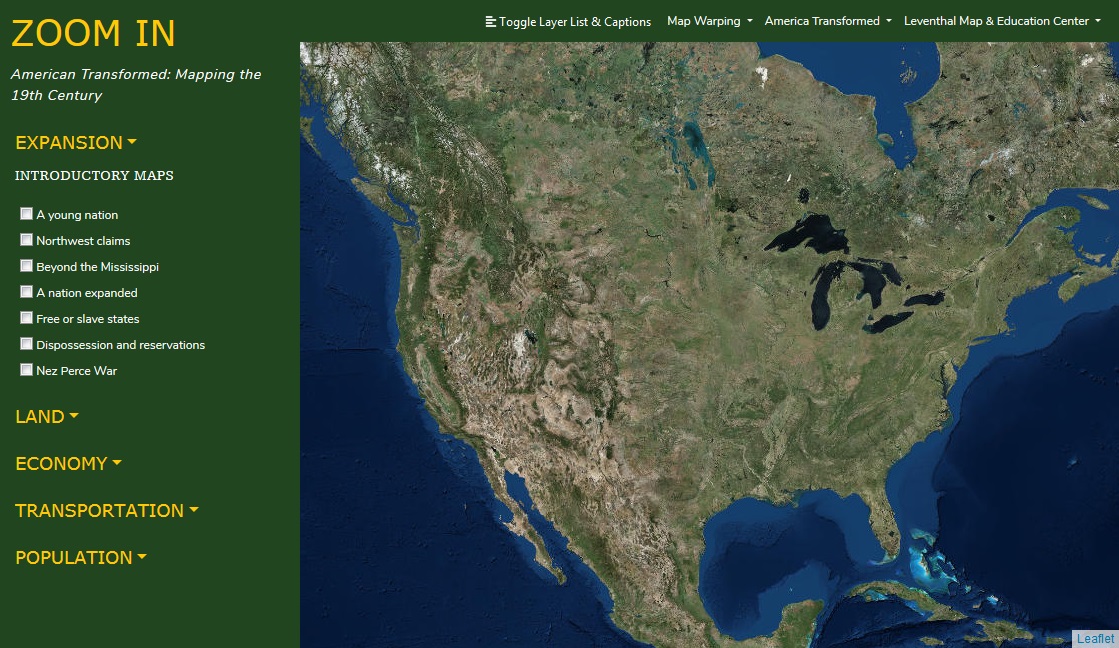

America Transformed: Mapping the 19th Century, is presented in two chapters:

Part One: The United States Expands Westward, 1800-1862

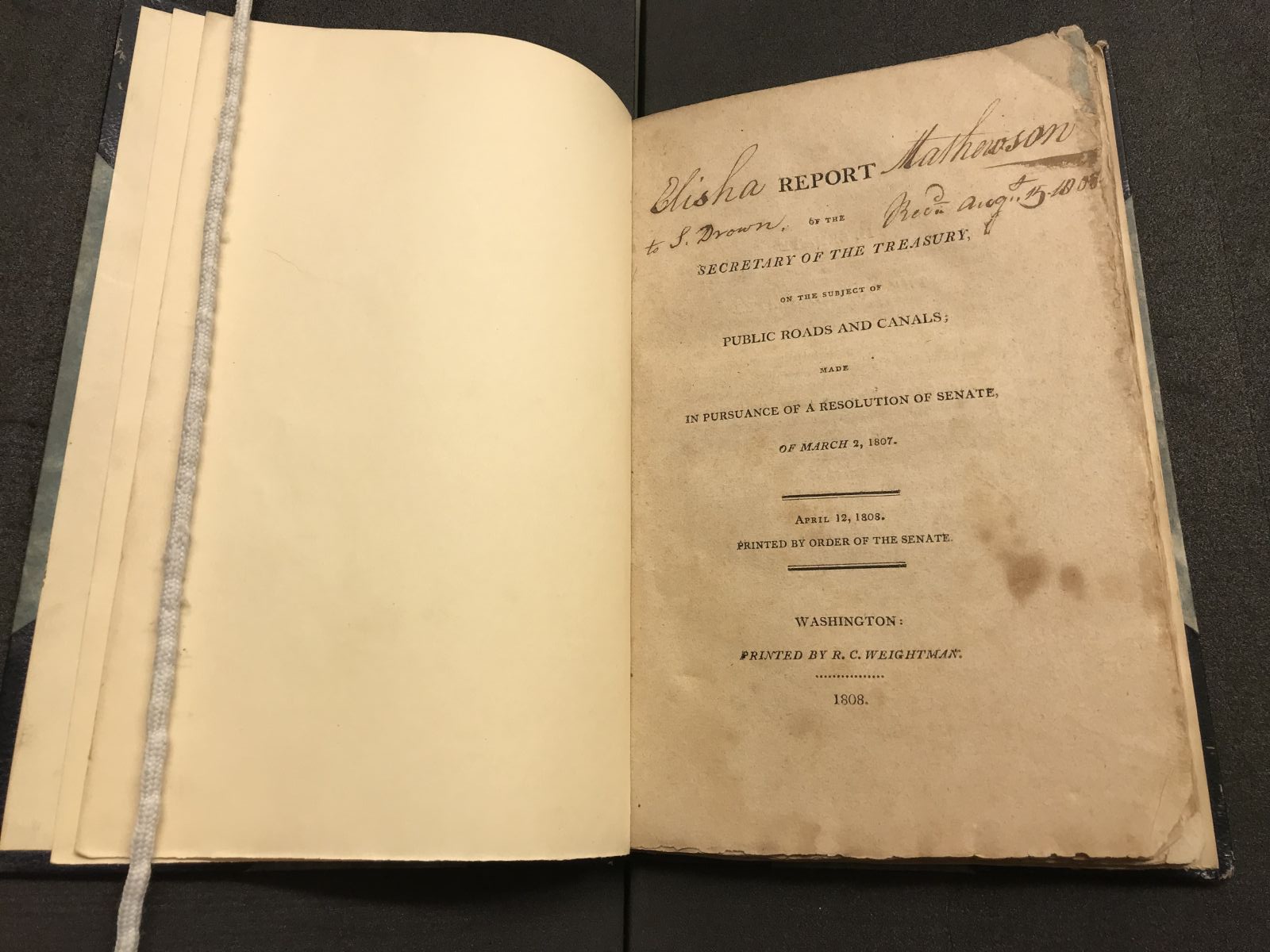

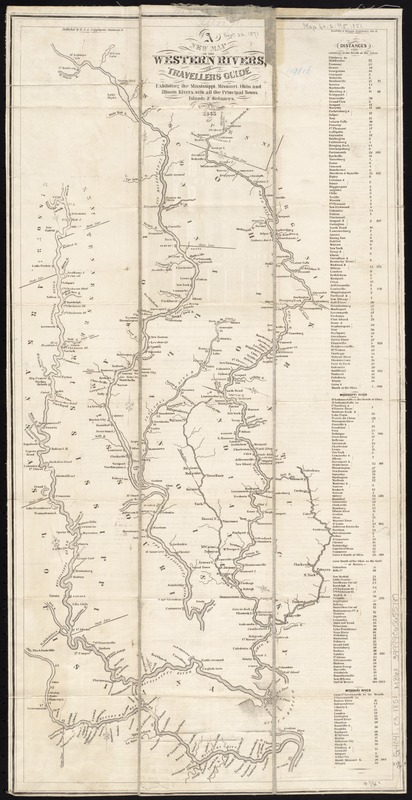

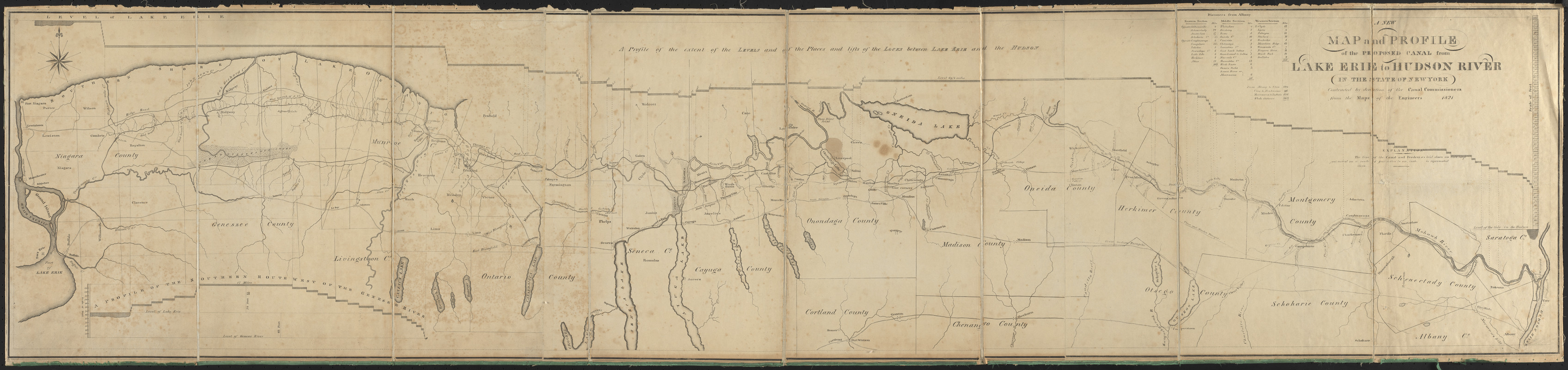

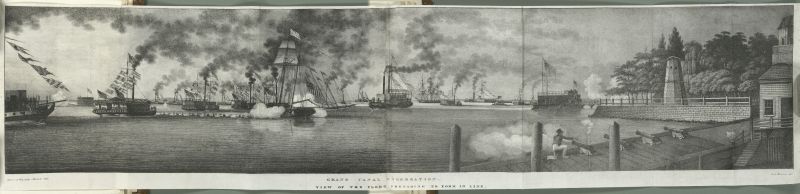

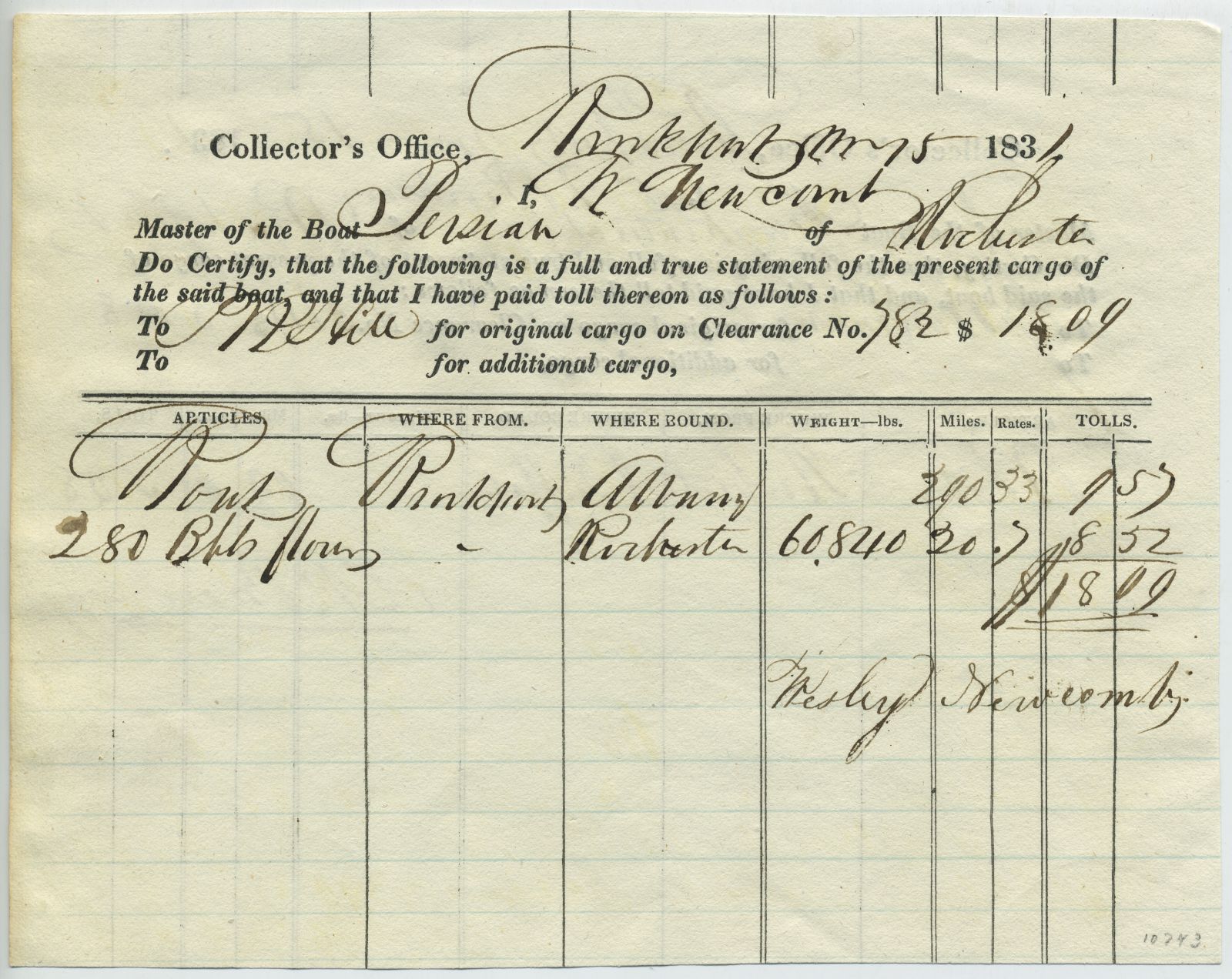

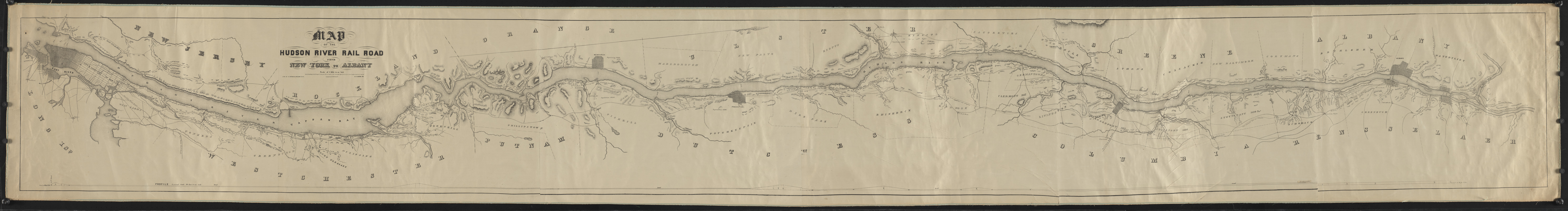

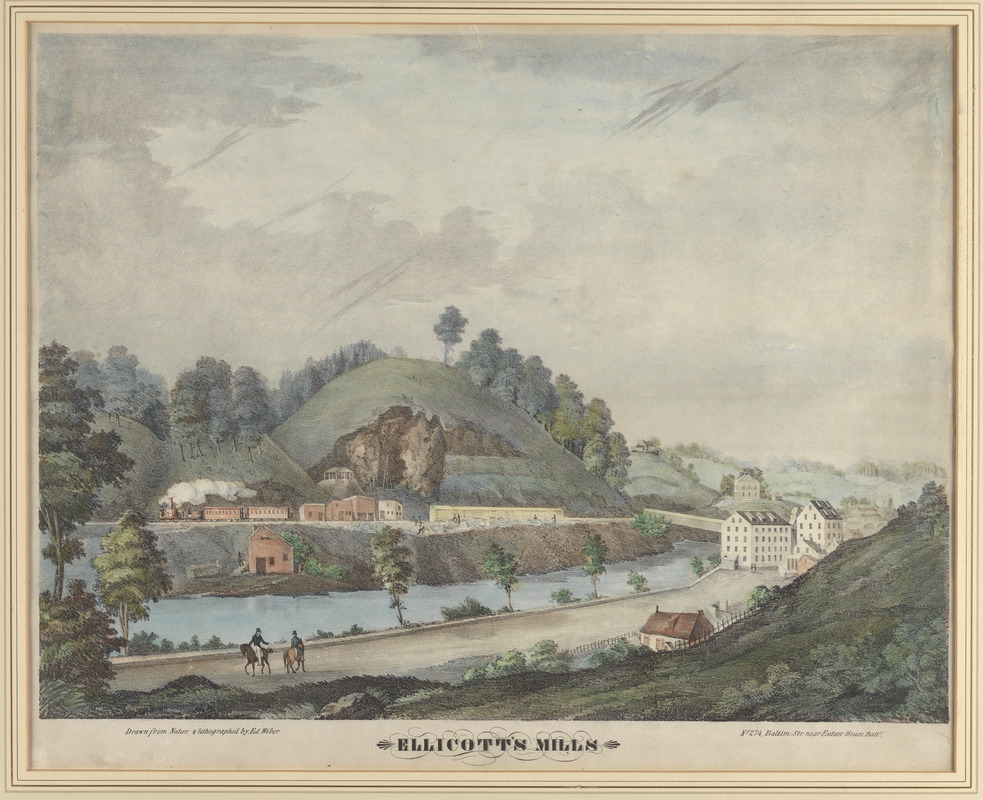

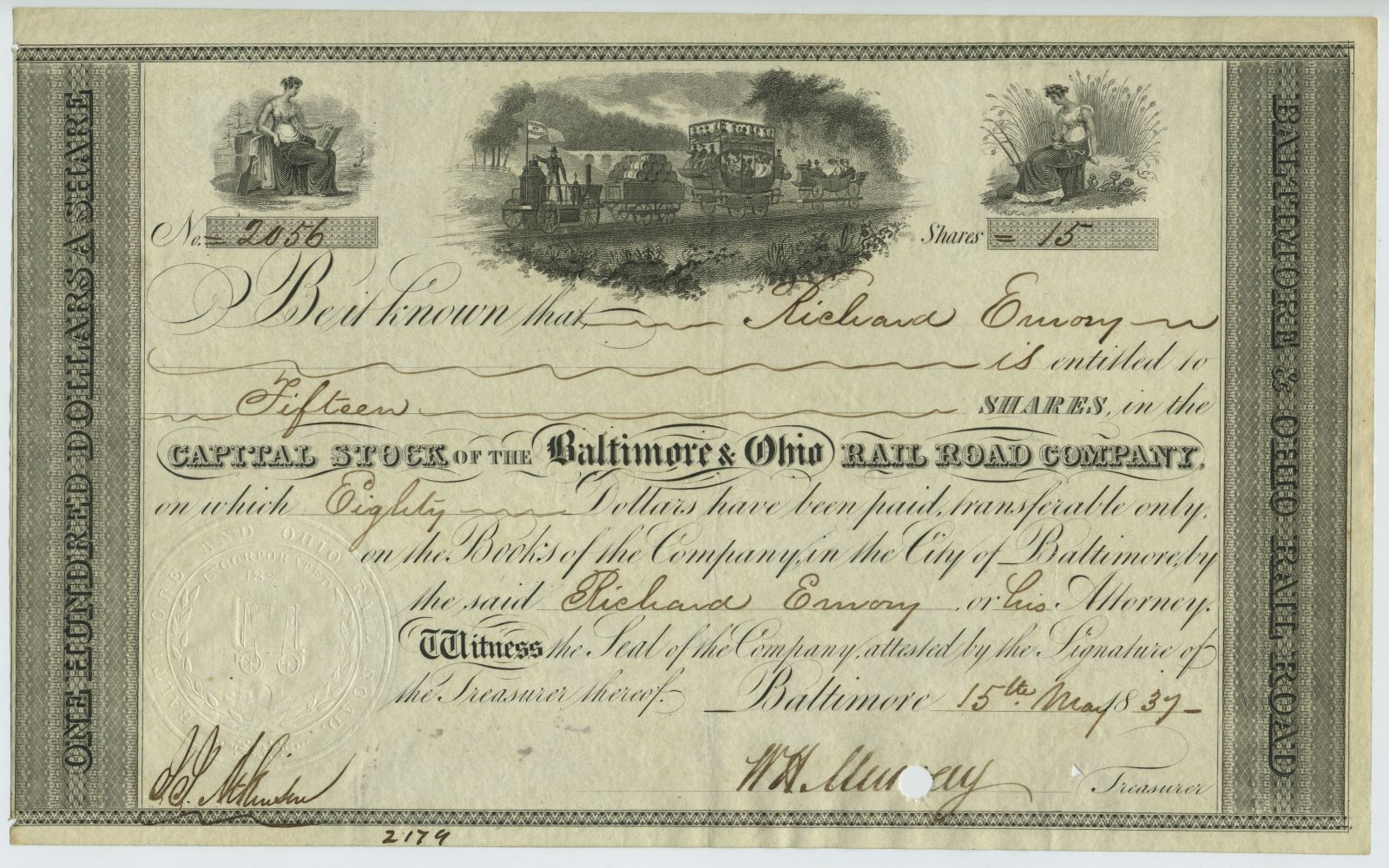

This exhibition begins at the end of the 18th century, when Euro-American settlers were exploring, surveying and rapidly taking over lands west of the Appalachians that were inhabited by Native peoples, as well as the French and Spanish. The newcomers developed canals, roads, and railroads, in many places appropriating Native trails, and created an integrated transportation network. Exploiting land and mineral resources, they initiated a capitalist economy based on agriculture, mining, and industry. This part of the story concludes with three significant events in the early 1860s that had major impact on the transformation of the nation’s physical and cultural landscape: the Civil War, the passing of the Homestead Act, and the authorization of the first transcontinental railroad.

VIEWPOINT: Maps were both the mechanisms for, and witnesses to, the betrayals of justice that made the violence of dispossession and extermination possible. We can stand in witness, too, if we have the courage to look closely and listen.

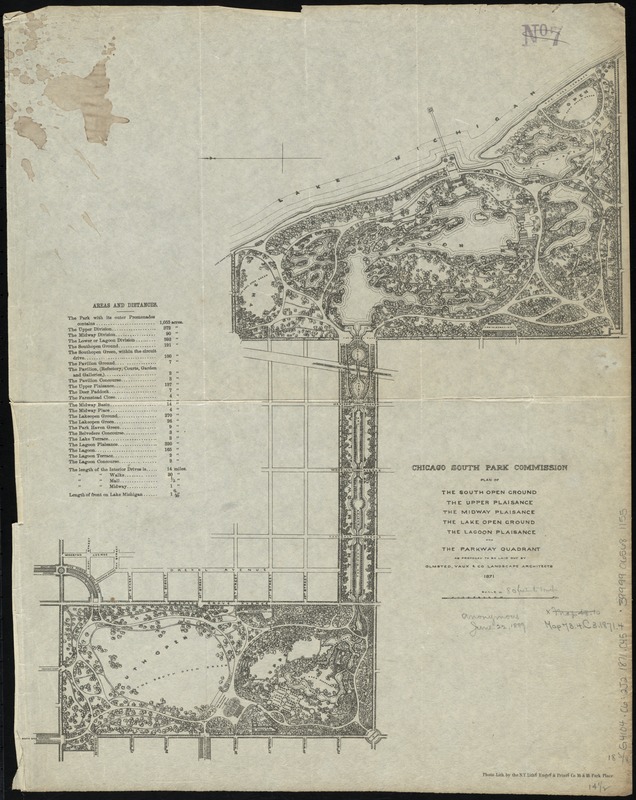

Part Two: Homesteads to Modern Cities, 1862-1900, November 2019-May 2020

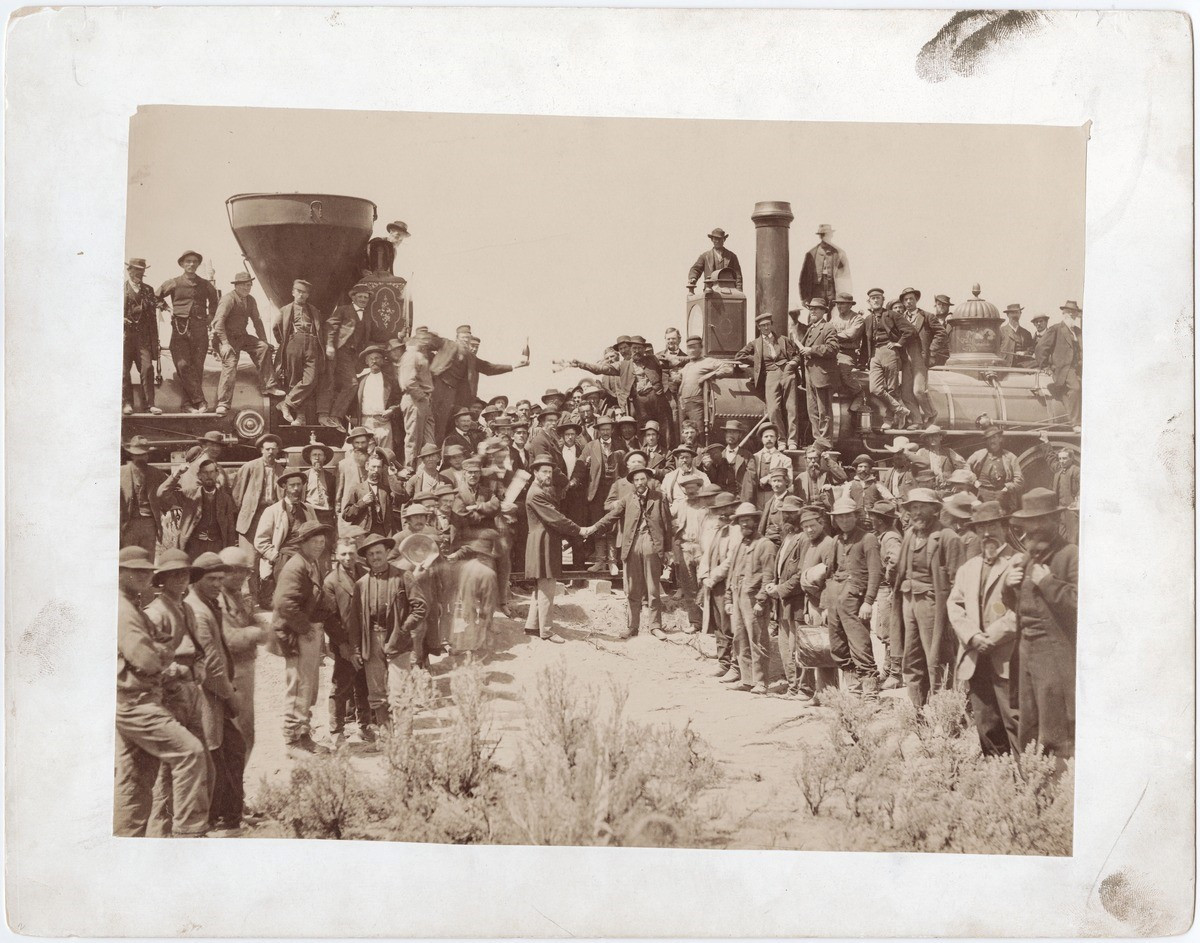

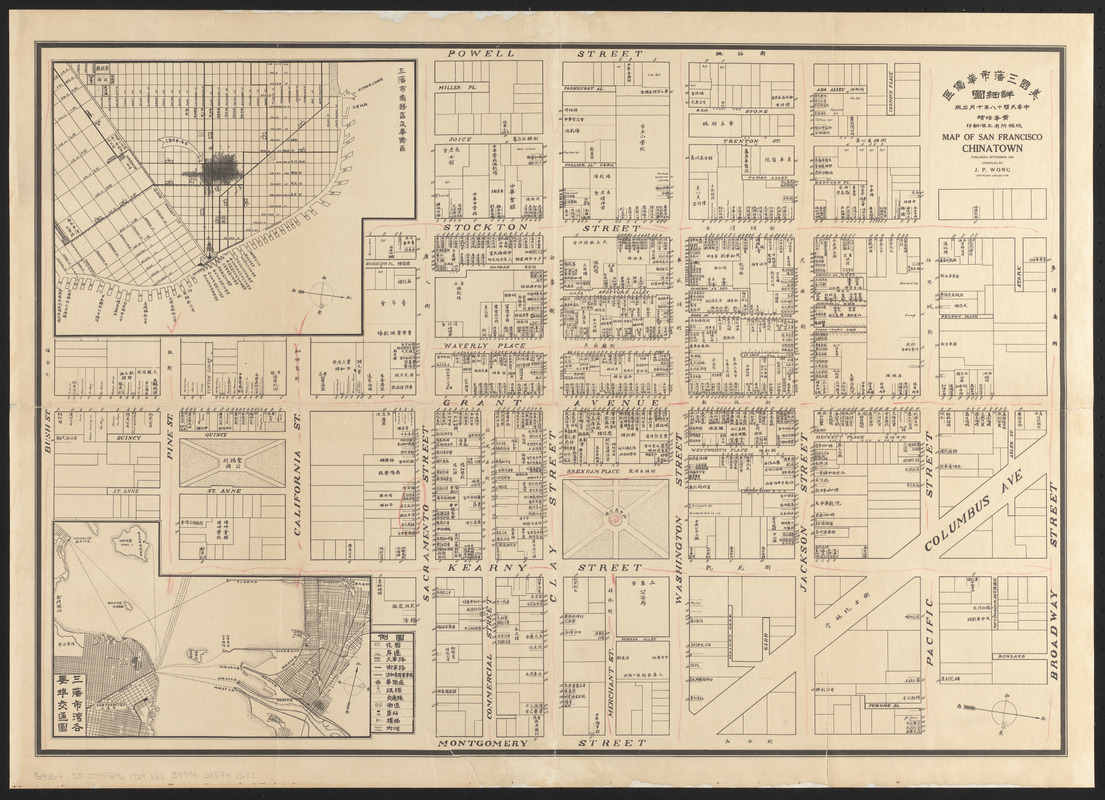

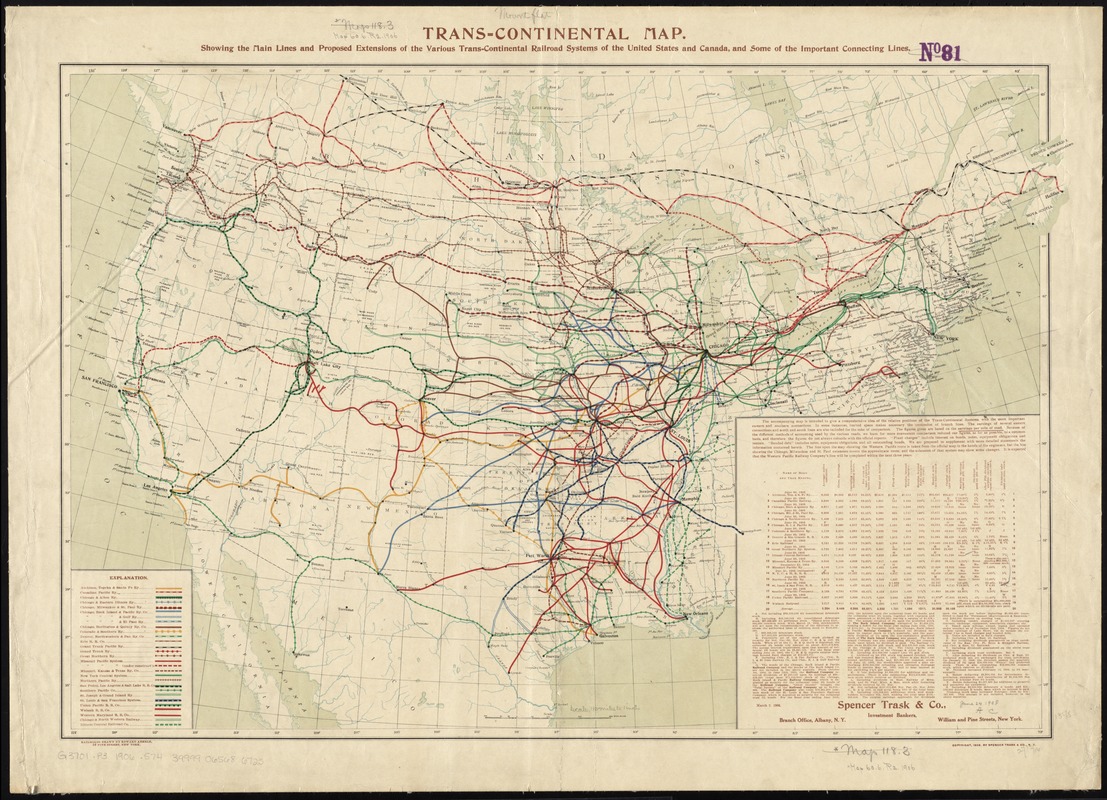

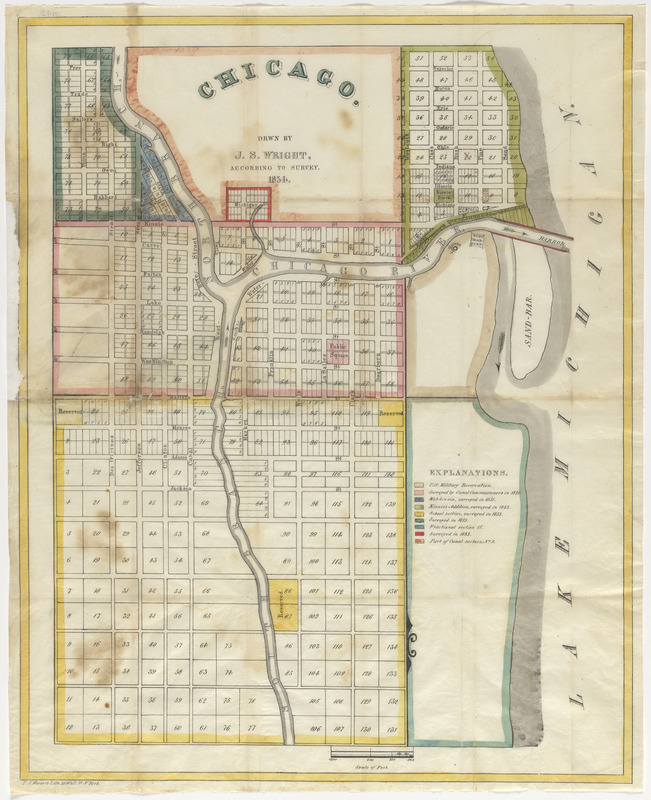

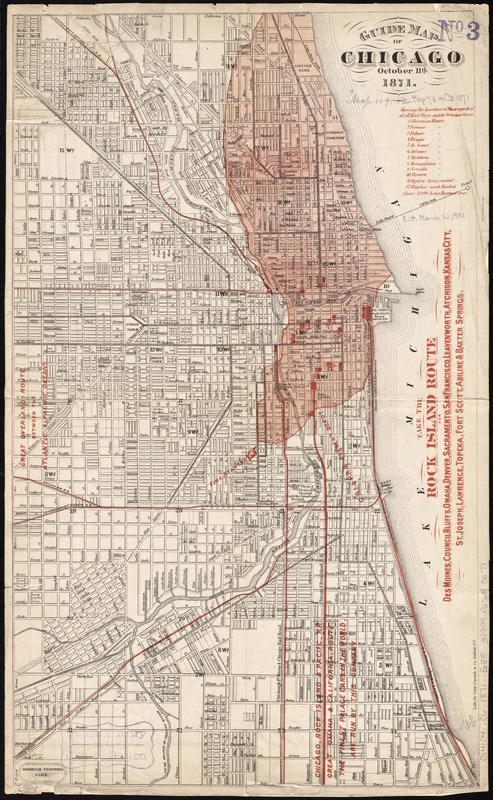

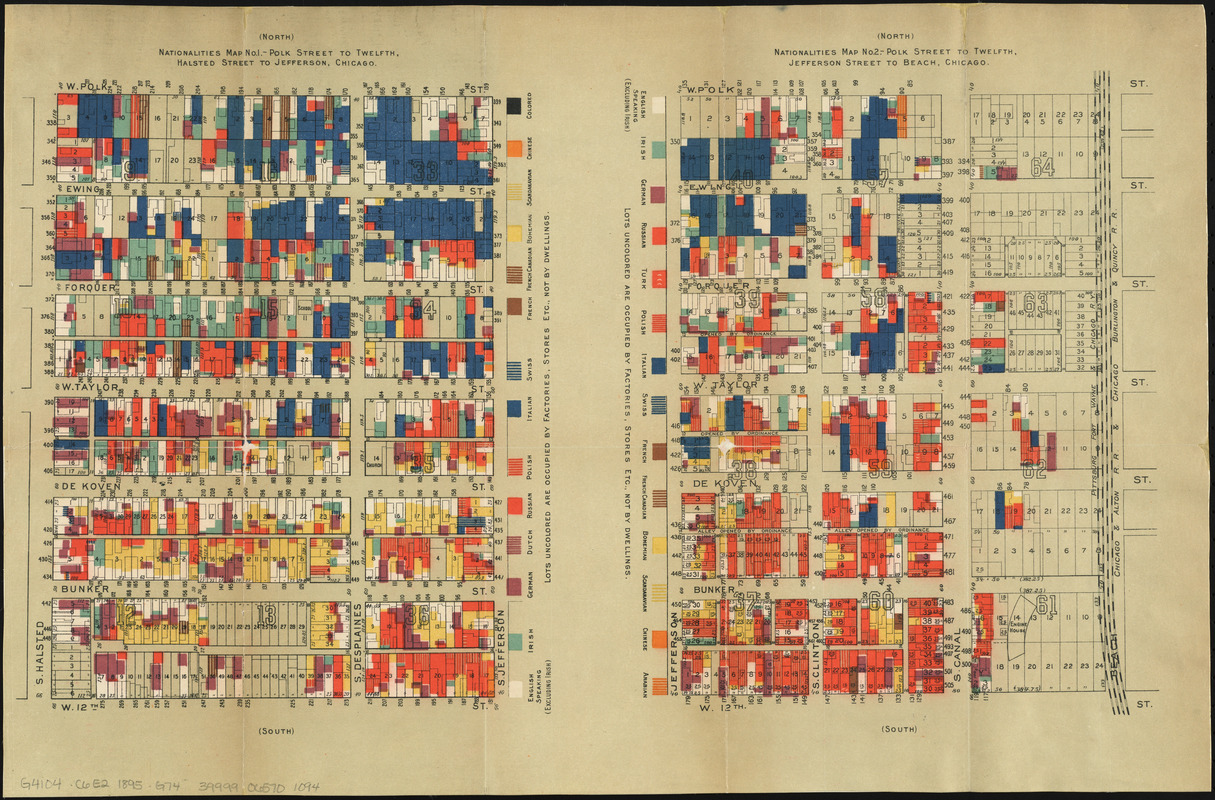

Homesteads to Modern Cities is the second part of this two-part exhibition and resumes the story of America Transformed in the early 1860s. Three events—the enactment of the Homestead Act, the authorization of the first transcontinental railroad, and the end of the Civil War—set in motion a frenzy of changes in American life. The northern and southern economies were rebuilt, settlement and resource exploitation expanded in the West, and urbanization and industrialization intensified in the Northeast and Midwest. Completion of the first transcontinental railroad finally linked the nation from coast to coast. Settlers continued to build a capitalist economy, no longer fueled by the labor of enslaved people but with increased reliance upon immigrant labor. And by the end of the nineteenth century, battles, treaties, and the establishment of reservations had dramatically hemmed in the land and life of Native nations. This exhibition concludes with the establishment of the modern American city, using Chicago as a case study.

The full-color, 212-page catalog of the two-part America

Transformed exhibition is available for purchase in both

hardcover and softcover editions. This richly illustrated

book features reprints, details, and captions of the maps

shown in the exhibition, along with seven essays exploring

the various dimensions of America’s momentous nineteenth

century. Purchase a catalog here.

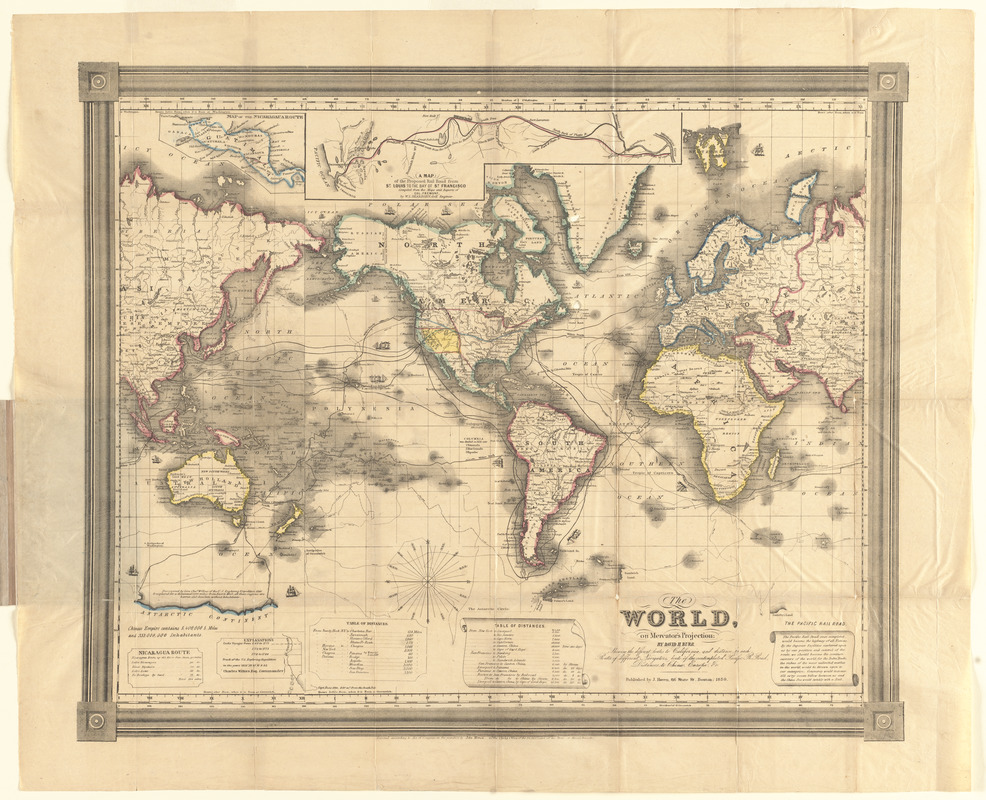

Overview

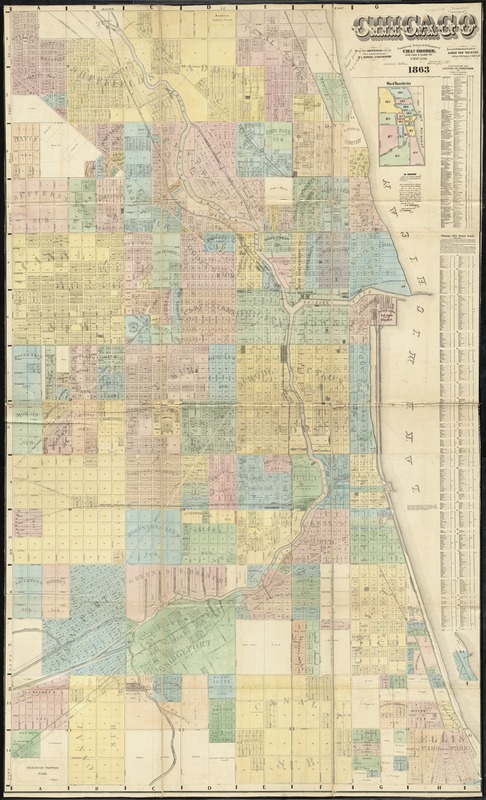

The maps in this introduction provide a chronological overview

of how the boundaries of the United States changed during the

19th century. Originally comprised of 13 eastern states, the

United States expanded to include 48 states and territories

spanning the breadth of the continent. The familiar, tidy

story of progress and inevitability of westward expansion is

promoted in many historical American maps, including the

growing demarcation of national, state, and county boundaries

that etched U.S. colonial power and ideology into the

landscape. Some of the maps presented here speak to encounters

with Native people and offer insight into the complex and

varied ways that Native and Euro-American people interacted,

coexisted, and fought. Maps created by or copied from Native

authors conceptualize mobility and relationships between

people and places rather than precise measurements and

boundaries. A bitter and uncomfortable undercurrent is the

reality of the oppression and dispossession of millions of

Native people.

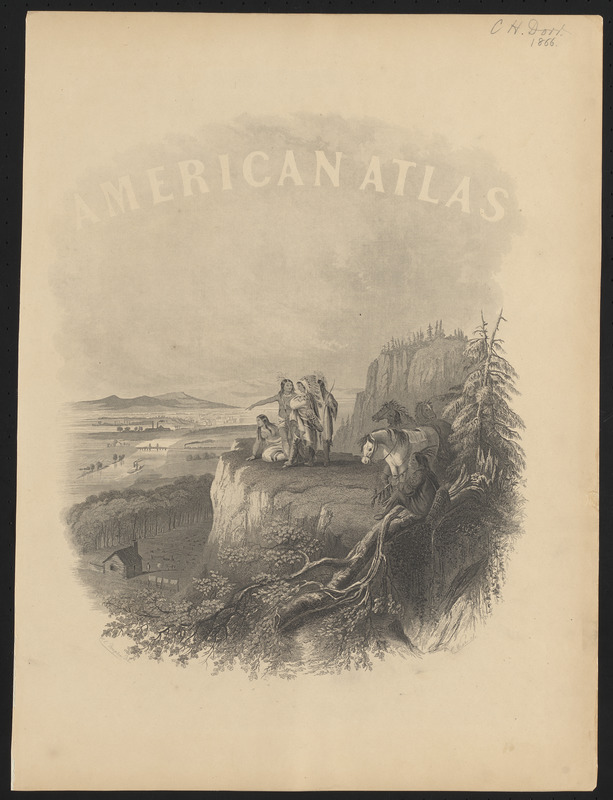

Alvin Jewett Johnson (1827-1884)

“American Atlas,”

from "Johnson’s New Illustrated (Steel Plate) Family

Atlas"

New York, 1866. Printed frontispiece, 18.5 x 14

inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center. Reproduction

2019.

Published in 1866, this family atlas frontispiece promoted a

popular, mythic vision of the American West. Four Native

people point to features of white advancement: a homestead

stands in an area cleared of trees, a steamship huffs toward a

railroad bridge, and smoke rises from a distant factory.

Bucolic depictions like these implied indigenous people

docilely accepted their displacement. They also portrayed

Native people as dwelling in an untouched, natural

environment, despite the reality that they, too, impacted the

land. The image promoted the idea that white settlers tamed

the wilderness and advanced their civilization where it was

“missing.”

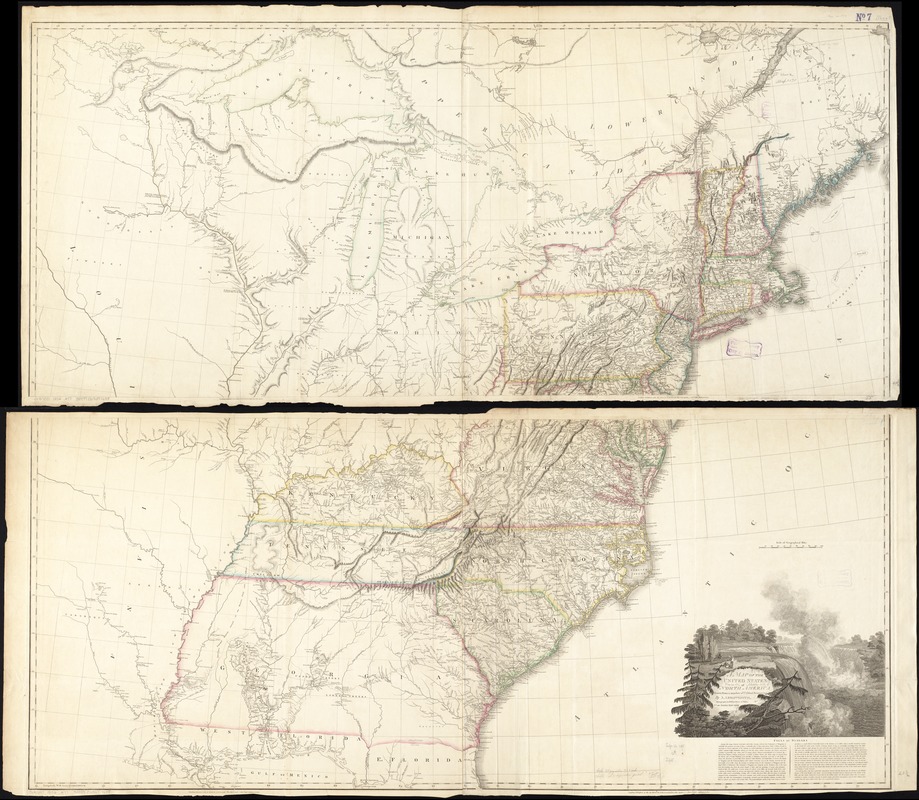

Aaron Arrowsmith (1750-1823)

"A Map of the United

States of North America"

London, 1802. Printed map, 48

x 55.5 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

Reproduction 2019.

This large wall map details the United States at the onset of

the 19th century. The young nation’s western boundary is the

Mississippi River, based on the 1783 Paris Peace Treaty. In

addition to the original 13 states, three new ones appear:

Vermont, Kentucky, and Tennessee. As Euro-American settlers

moved across the Appalachian Mountains, they encountered

Native and French communities, including the Tsalagi

(Cherokee), Chikasha (Chickasaw), Chahta (Choctaw), and

Mvskoke (Creek) who inhabited expansive ancestral lands in the

southern portion of this trans-Appalachian region. An image of

Niagara Falls, which became part of the nation’s popular

iconography, adorns the cartouche.

Nicholas King (1771-1812), after Meriwether Lewis and

William Clark

"Map of Part of the Continent of North

America . . . from the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean . .

."

Washington, D.C., 1806? Manuscript map, 26.5 x 38

inches. Courtesy of the

Boston Athenaeum. Reproduction 2019.

Following the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France

in 1803, President Thomas Jefferson commissioned the Corps of

Discovery to explore and map the new territory, develop trade

and diplomatic relations with tribal nations, and establish a

claim to the Pacific Northwest. Commanded by Meriwether Lewis

and William Clark, the Corps kept a daily record of geographic

observations and prepared numerous manuscript maps

incorporating information provided by Native people.

Particularly noteworthy are the names of tribal communities,

annotated in red ink. This was the federal government’s first

attempt to accurately map the presence of Native peoples (and

number of warriors) west of the Mississippi River. These lands

were claimed by the United States but firmly controlled by

Native peoples.

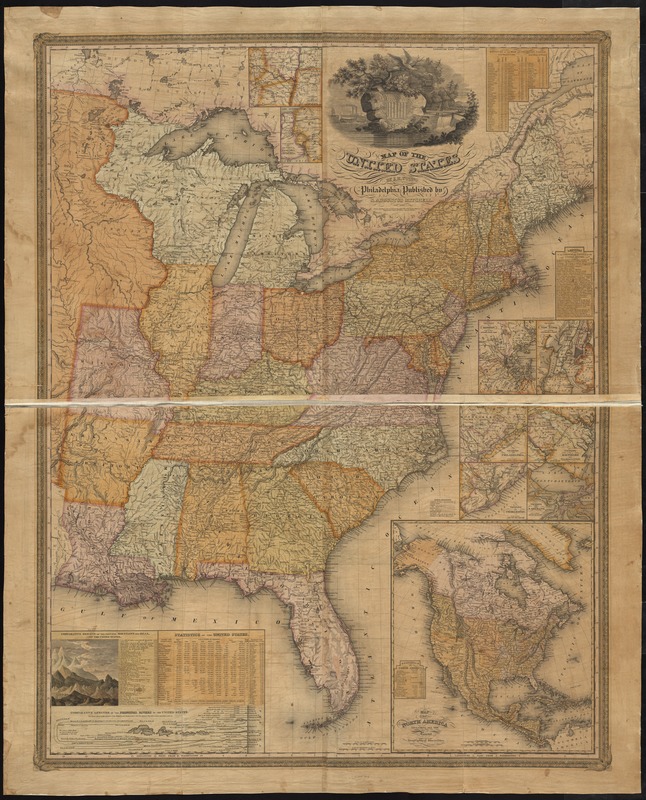

James Hamilton Young

"Map of the United States"

Philadelphia,

1831. Printed map, 42.5 x 33.5 inches. Leventhal Map and

Education Center. Reproduction 2019.

By 1831, the land east of the Mississippi had been divided

into 24 states and the Michigan territory. In addition,

American settlement and Native dispossession started to expand

west of the Mississippi with the addition of Louisiana,

Arkansas, and Missouri. The mapmakers also labeled the lands

occupied by the Tsalagi (Cherokee), Mvskoke (Creek), Chikasha

(Chickasaw), and Chahta (Choctaw) in large capital letters,

although just a year earlier, the federal government had

enacted the Indian Removal Act, which forced many tribes from

their ancestral homelands. The law paved the way for the Trail

of Tears, the name given to a series of forced relocations of

these Native nations.

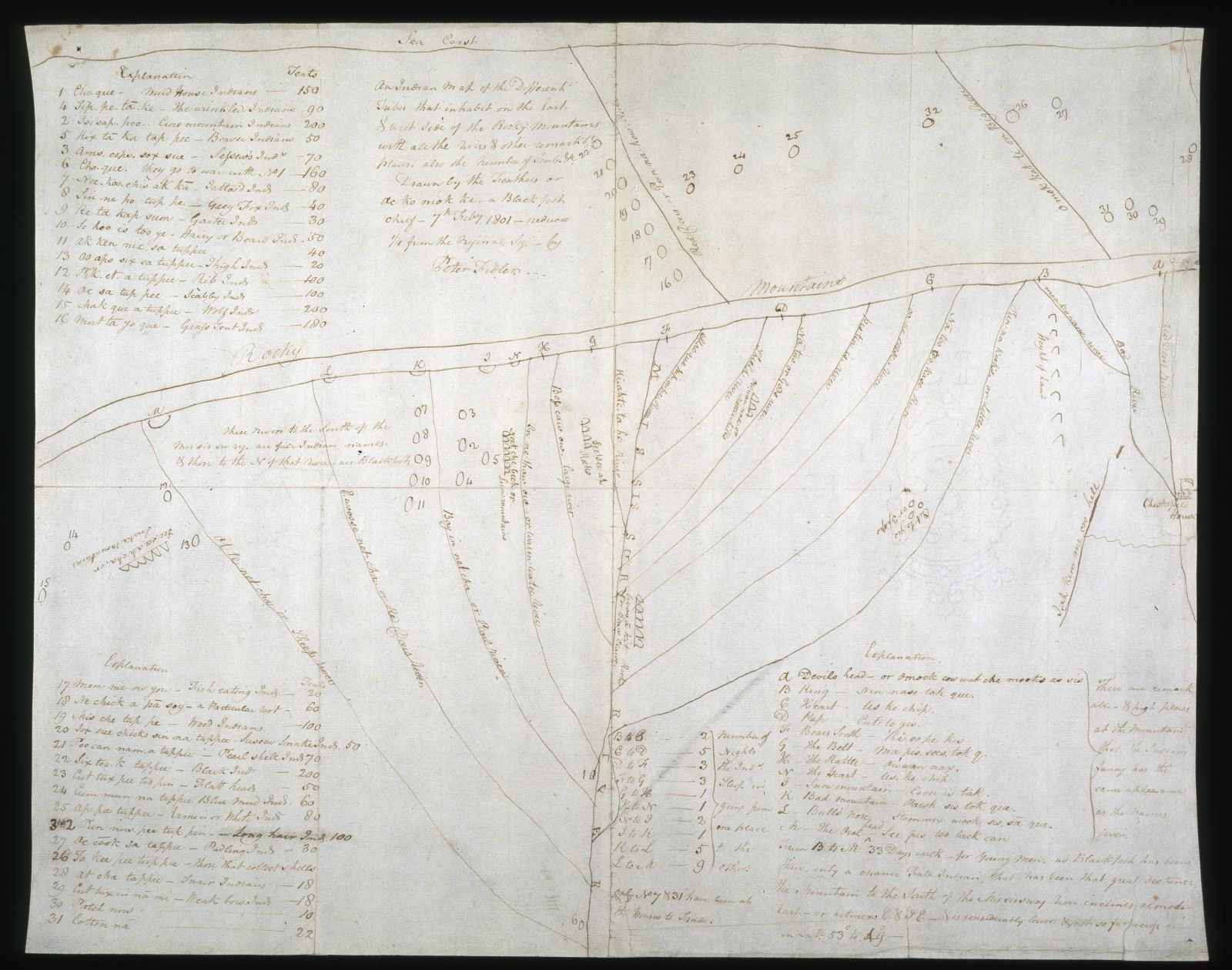

Peter Fidler (1769-1822) after Ac ko mok ki

"An

Indian Map of the Different Tribes, that Inhabit the East

and West Side of the Rocky Mountains . . ."

1801.

Manuscript map, 15 x 19 inches. Courtesy of Hudson's Bay

Company Archives,

Provincial Archives of Manitoba,

G.1/25. Reproduction 2019.

Peter Fidler, cartographer and fur trader, recorded this map

in 1801 based on one provided by Ac ko mok ki, a Blackfoot

chief. West is at the top, and a double line represents the

Rocky Mountains. Below, the headwaters of the Missouri and

Saskatchewan River systems flow eastward down the map. Over 30

tribal nations in the upper Great Plains region are noted.

When the map was forwarded to London, the physical geography

was integrated into a printed map but the data pertaining to

the tribal nations was omitted to suggest that this region was

uninhabited.

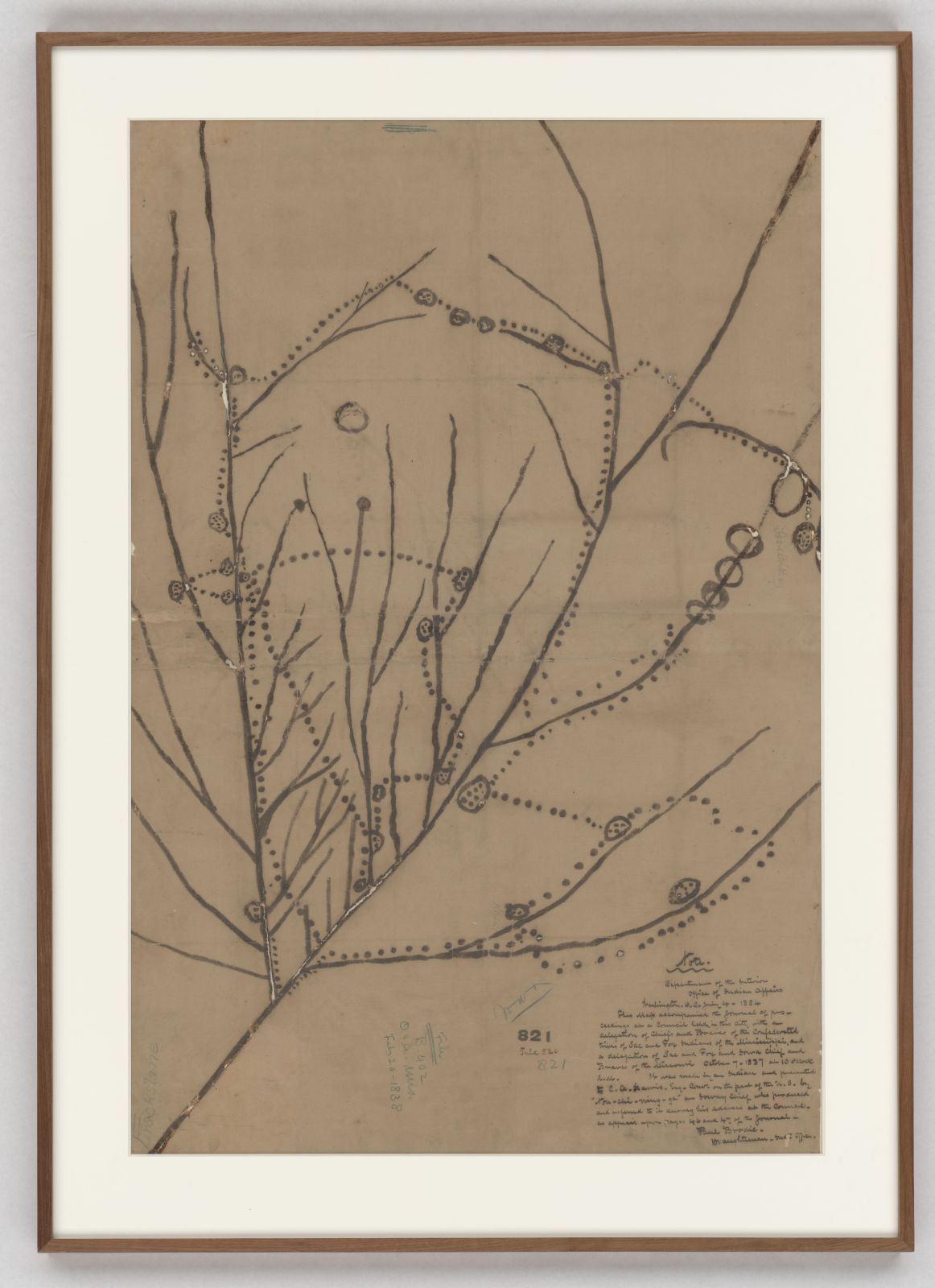

"Non-Chi-Ning-Ga’s Map of the Migration of his Indian

Ancestors"

1837. Manuscript map, 41 x 27.5 inches.

Courtesy of

National Archives and Records Administration,

Record Group 75, map 821. Reproduction 2019.

An Ioway chief named Non-Chi-Ning-Ga (“No Heart of Fear”)

prepared this schematic diagram of the Upper Mississippi and

Missouri River drainages for an 1837 treaty council in

Washington, DC. In an effort to prove the lands were theirs,

rather than Sac and Fox, the map records Ioway place names and

ancestral village sites. The tribe’s migration routes for two

centuries are marked in dotted lines, from Green Bay on Lake

Michigan (on the right) through Wisconsin to the Mississippi

River (central diagonal line) to the Missouri (vertical line

on left). Although the Sac and Fox did not dispute the history

expressed in this map, the U.S. government forced the Ioway to

relocate to reservations.

Joseph Hutchins Colton (1800-1893)

"Colton's Map of

the United States of America … from the Atlantic to the

Pacific Ocean"

New York, 1854. Printed map, 47 x 55

inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center. Reproduction

2019.

During the 1840s and early 1850s, the political geography of

the West changed dramatically. The nation annexed Texas,

established the 49th parallel as its northwestern boundary,

claimed the Oregon Territory, and won land from Mexico

following the Mexican-American War. By the time this map was

published in 1854, the United States included 31 states and

seven territories. Commercially published maps like this one

celebrated the nation’s expansion with small vignettes

dispersed throughout these newly acquired territories

depicting Native people, wildlife, and a wagon train. It also

suggests a unified nation, but a statistical table enumerating

free and enslaved population alludes to conflicts over whether

to extend slavery into the western territories and foreshadows

the impending Civil War.

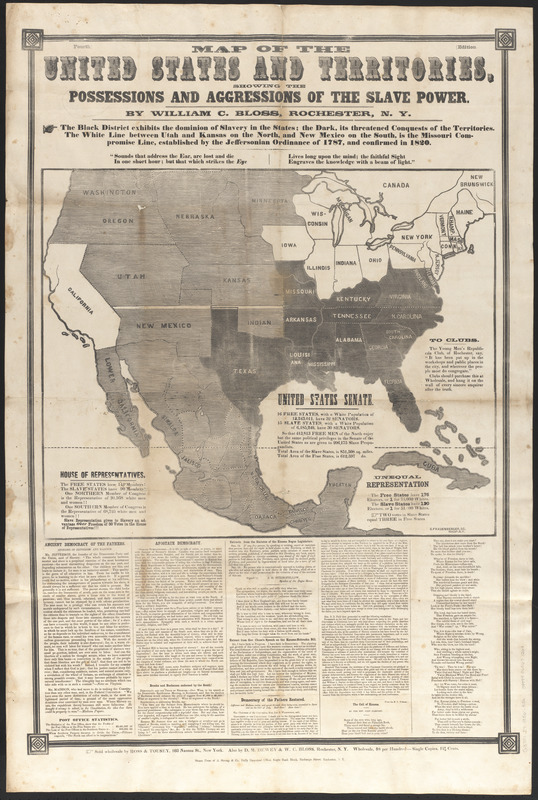

William C. Bloss (1795-1863)

"Map of the United

States and Territories Showing the Possessions and

Aggressions of the Slave Power"

New York and Rochester,

NY, 1856? Printed broadside, 41.5 x 27.5 inches. Leventhal

Map and Education Center. Reproduction 2019.

While Colton’s map suggests a unified nation extending from

the Atlantic to the Pacific, this broadside published about

the same time boldly addresses the slavery issue. It

identifies free states in white, slave states in black, and

contested territories in gray. Issued during the 1856

presidential election, this stark graphic implicitly supports

the candidacy of Republican John C. Frémont, who opposed

slavery’s expansion. It also forcefully challenges the

so-called Three-Fifths Compromise which counted three out of

five slaves toward calculating southern political

representation, while denying those enslaved peoples any

voting privileges or freedom.

U.S. General Land Office

"Map of the United States and

Territories, Showing the Extent of Public Surveys. . ."

Washington,

DC, 1871. Printed map, 27.5 x 55 inches. Leventhal Map and

Education Center. Reproduction 2019.

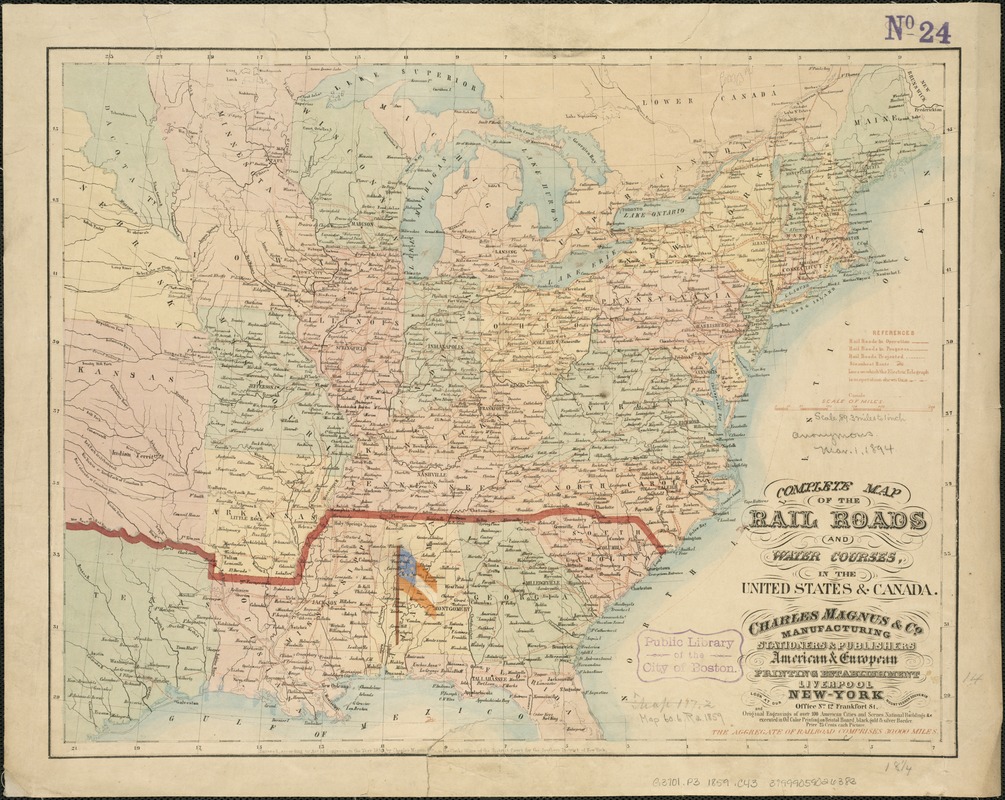

Published shortly after the American Civil War, this map

depicts a reunited nation, but it also provides an inventory

of land and mineral resources. While the General Land Office,

the federal agency responsible for surveying and selling

public lands, produced this map as a yearly update of its

activities, it also promoted further expansion of western

settlement. The square grid pattern appearing in most states

west of the Appalachian Mountains indicates the extent of

public land or township surveys. Color coding identifies the

location of mineral resources. Reflecting the efforts to unify

the nation after the Civil War, this map marks the route of

the first transcontinental railroad.

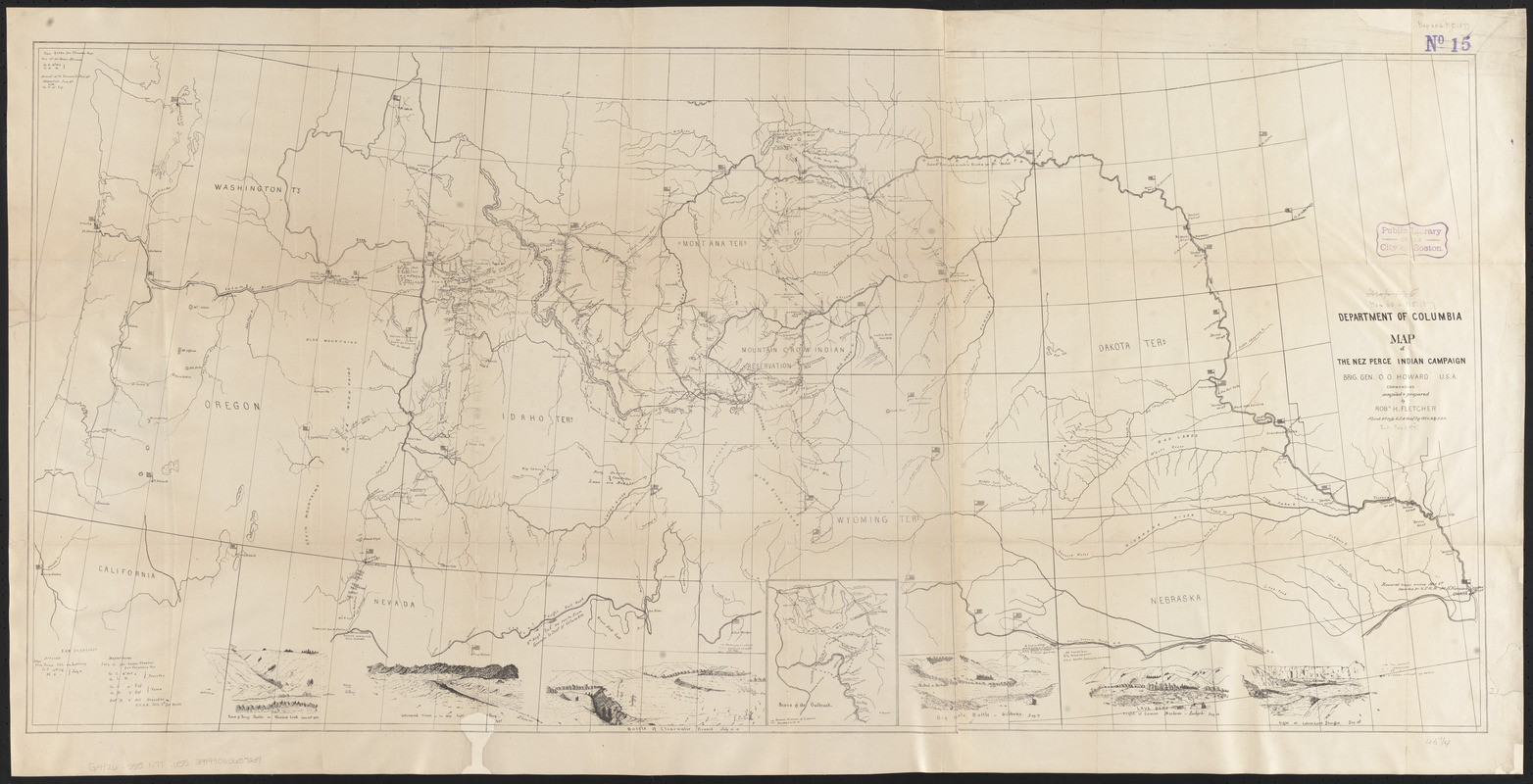

Robert H. Fletcher

"Map of the Nez Perce Indian

Campaign, Brig. Gen. O. O. Howard, Commanding"

Washington,

DC, 1877. Printed map, 24 x 47.25 inches. Leventhal Map and

Education Center. Reproduction 2019.

This military map records the Nez Perce War in 1877, one of

the final campaigns of the U.S. Army against the tribal

nations of the Pacific Northwest. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard, a

Union Civil War leader, Commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau,

and a founder of Howard University, led U.S. troops. They

pursued several bands of Nimiipuu (Nez Perce) who refused to

surrender their ancestral lands and move to a smaller

reservation in Idaho. Threatened with forced removal, they

embarked on a northward trek to find sanctuary in Canada.

After a fighting retreat of 1,170 miles and 18 skirmishes and

battles, they surrendered just south of the Canadian

border.

National Publishing Company

"The United States of

America: Including All Its Newly Acquired Territory"

Boston,

1902. Printed map, 38 x 55 inches. Leventhal Map and

Education Center. Reproduction 2019.

While this information-packed map summarizes the nation’s

political geography and population growth after a century of

territorial expansion and native removals, it also documents a

new arena for empire building beyond the continent. Brightly

colored boundaries outline 48 states and organized

territories, as well as counties within each. Settlement in

the eastern half of the country was denser than the West,

which was characterized by much larger states and counties.

Graphs and tables demonstrate the growth of population from

3.9 million in 1790 to over 76 million in 1900. Marginal

insets depict Alaska and Hawaii (taken by a coordinated

overthrow of the Hawaiian Queen just a few year prior), as

well as “newly acquired territories” in the Caribbean and

across the Pacific.

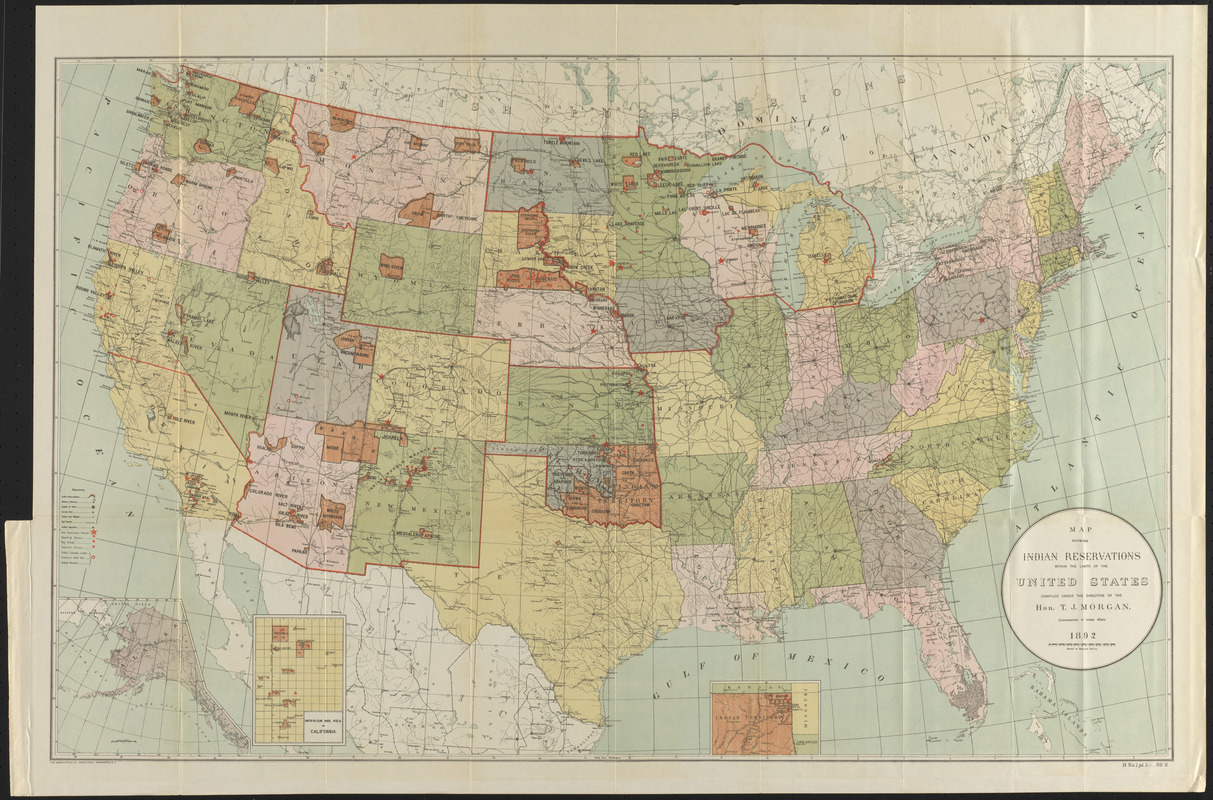

Commissioner of Indian Affairs

"Map Showing Indian

Reservations within the Limits of the United States"

Washington,

DC, 1892. Printed map, 38 x 55 inches. Courtesy of Lawrence

Caldwell. Reproduction 2019.

By the 1890s, many Native tribes were displaced and forced to

live on reservations, comprising a fraction of their homeland,

on territory designated as the most undesirable for settlers

or in totally different environments than originally

inhabited. This map depicts the locations, sizes, and

boundaries of reservations, which were usually established by

treaties ratified by the U.S. Senate. In many cases Congress

did not ratify treaties signed in good faith by Native

peoples, and the agreed upon reservation boundaries were

renegotiated to the benefit of the government and the states.

In 1887, the Dawes Act (General Allotment Act) further reduced

the size of reservations by permitting the federal government

to assign land to individual Native families, rather than

tribes. The law fragmented reservations and opened more land

to non-Native settlers.

James Wilson (1763-1855)

"A New American Terrestrial

Globe"

Bradford, VT, 1811. Globe, 17 x 17 x 19 inches.

Leventhal Map and Education Center.

At the beginning of the 19th century, Americans had access to

globes, but they had to import them from Europe. James Wilson,

who became the first to produce globes in the United States,

made this globe in 1811. Rather than identifying the specific

region that was part of the United States, he labeled the

entire continent “America.” Wilson marked the boundaries of

the eastern states and Louisiana Purchase and noted the names

of several tribal nations. Since white cartographers had

extensively mapped the East, the globe features more detail in

that region than in the West.

James T.B. Ives (1839-1915)

"Historical Map Showing

the Successive Acquisitions of Territory by the United

States of America"

New York, 1896. Mechanical map, 24.5 x 34 inches. Courtesy

of

Barry MacLean Collection.

The boundaries of the United States transformed during the 19th century. Mapmaker James Ives created this mechanical map to help people, especially students, visualize these changes. The base map labels the tribes that occupied different regions, while the upper layers represent the territorial growth of the United States. The mechanized pieces of this cartographic puzzle include the colonies in 1776, the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, and the Gadsden Purchase in 1853. The map told a story of the seemingly inevitable process of expansion and emphasized nation-building by treaties rather than the violence of war.

1a. LAND 1800-1862: Exploring, Surveying, and Conserving the Land

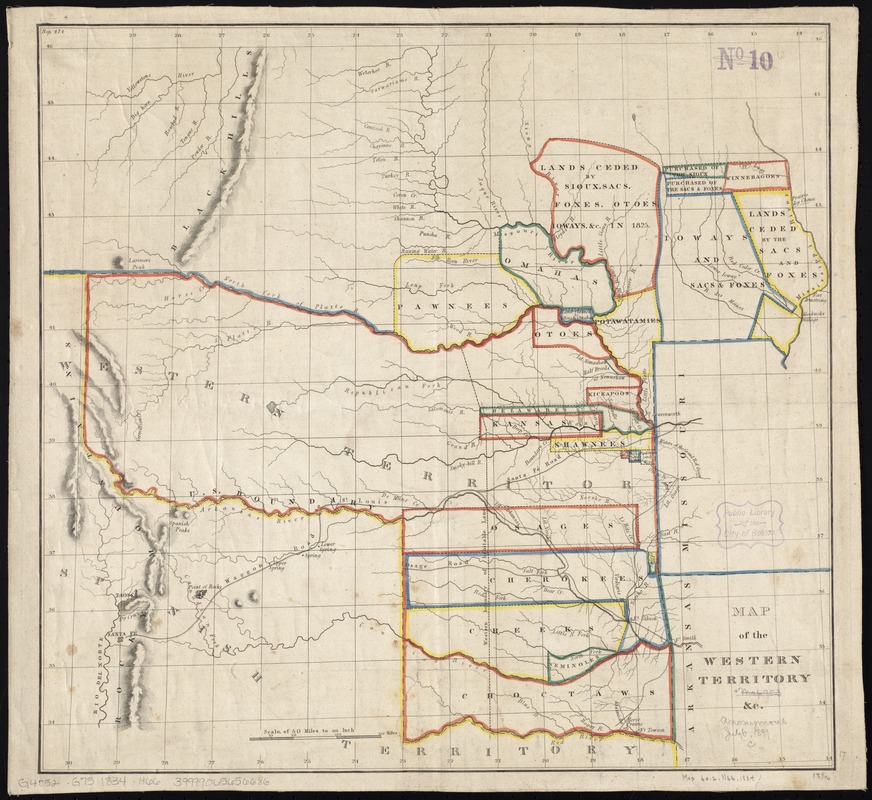

To most people of European descent, the land west of the Mississippi River was unknown, although Native peoples were deeply knowledgeable about the land on which they hunted, traded, farmed, and developed communities. In the 1780s, government officials initiated the settler-colonial process of westward expansion. The maps and artifacts in this exhibition illustrate how Congress set the principles for surveying and selling public lands that had been gained through purchase, treaty, trickery, warfare, and forced removal.

Surveyors standardized the practice of dividing land into six-mile square townships providing the foundation for settlement patterns in western states. Government surveys noted the land claims of earlier French and Spanish inhabitants but failed to recognize lands claimed by Native tribes.

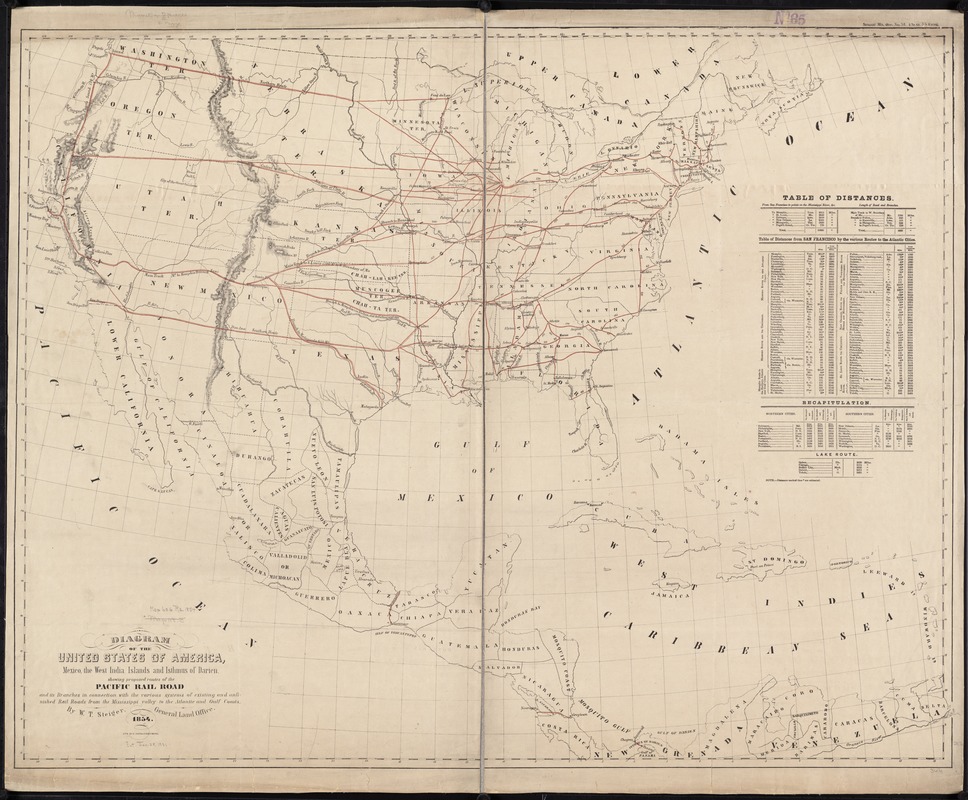

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark set out to inventory and

map the newly acquired Louisiana Purchase in the early 1800s.

Their trip paved the way for similar government-sponsored

expeditions and culminated in the 1850s with the Pacific

Railroad Surveys, which mapped potential routes for the first

transcontinental railroad. Each of these efforts brought back

cartographic and scientific data about the inhabitants,

landscape, natural resources, and wildlife. By the final third

of the century, many Americans became concerned about

conserving these natural resources and landscapes that were

rapidly disappearing through economic exploitation.

Frank Bond (1856–1940) and I. P. Berthrong

“United

States Showing Routes of Principal Explorers and Early Roads

and Highways”

Washington, DC, 1908. Printed map, 23.5

x 32 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

Reproduction, 2019.

Frank Bond, a General Land Office surveyor, draftsman, and

finally Chief Clerk, created this thematic, historical map

that was atypical of other GLO publications. He compiled the

major Spanish, Dutch, French, British, and American routes

during four centuries of Euro-American exploration. This

colorful presentation was overlaid on a standard base map that

showed the extent of township surveys by the beginning of the

20th century. The map demonstrated the current state of

geographical knowledge and suggested that by this time there

was little unmapped land.

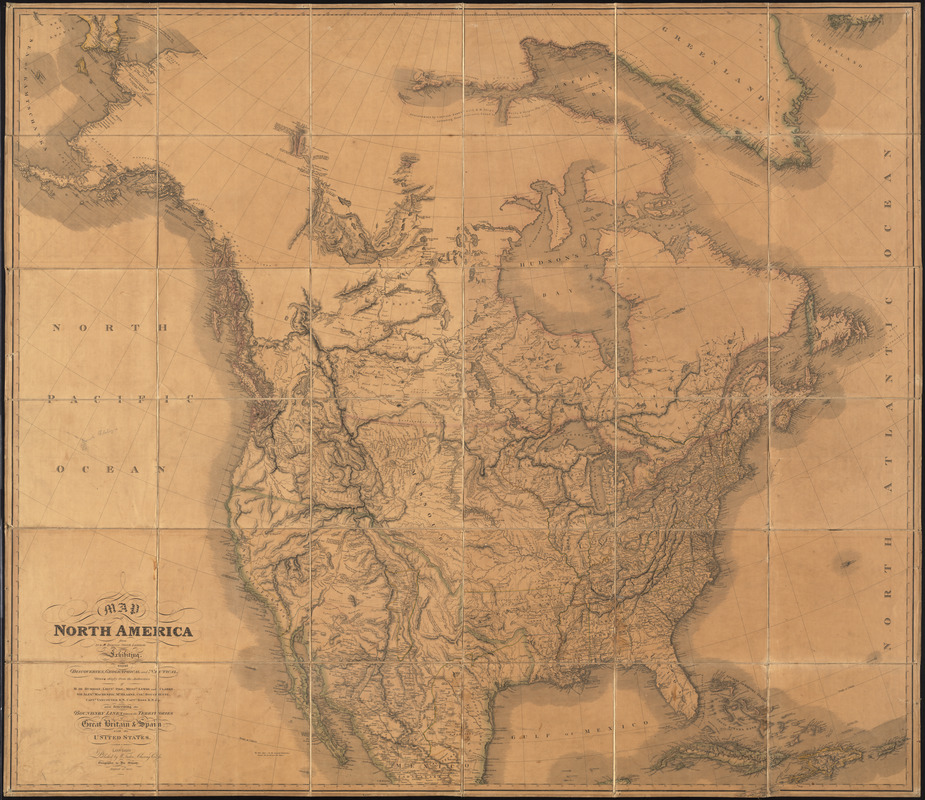

William Faden (1749–1836)

“Map of North America from

20 to 80 Degrees North Latitude: Exhibiting the Recent

Discoveries …”

London, 1820. Printed map, 59 x 66

inches. Courtesy of Lawrence Caldwell. Reproduction, 2019.

This large wall map integrated topographic and hydrographic

detail gained from various European and American explorations

of interior North America. It included data from expeditions

led by Alexander von Humboldt (northern Mexico), Alexander

MacKenzie (Canadian Great Plains), and George Vancouver

(Pacific northwest coast), as well as Meriwether Lewis,

William Clark, and Zebulon Pike, all of whom were commissioned

by President Thomas Jefferson to explore the newly acquired

Louisiana Territory. This accumulated knowledge demonstrated

that the western part of the continent was not dominated by a

single mountain range as was previously hypothesized, but by a

complex series of ranges that came to be known as the Rocky

Mountains.

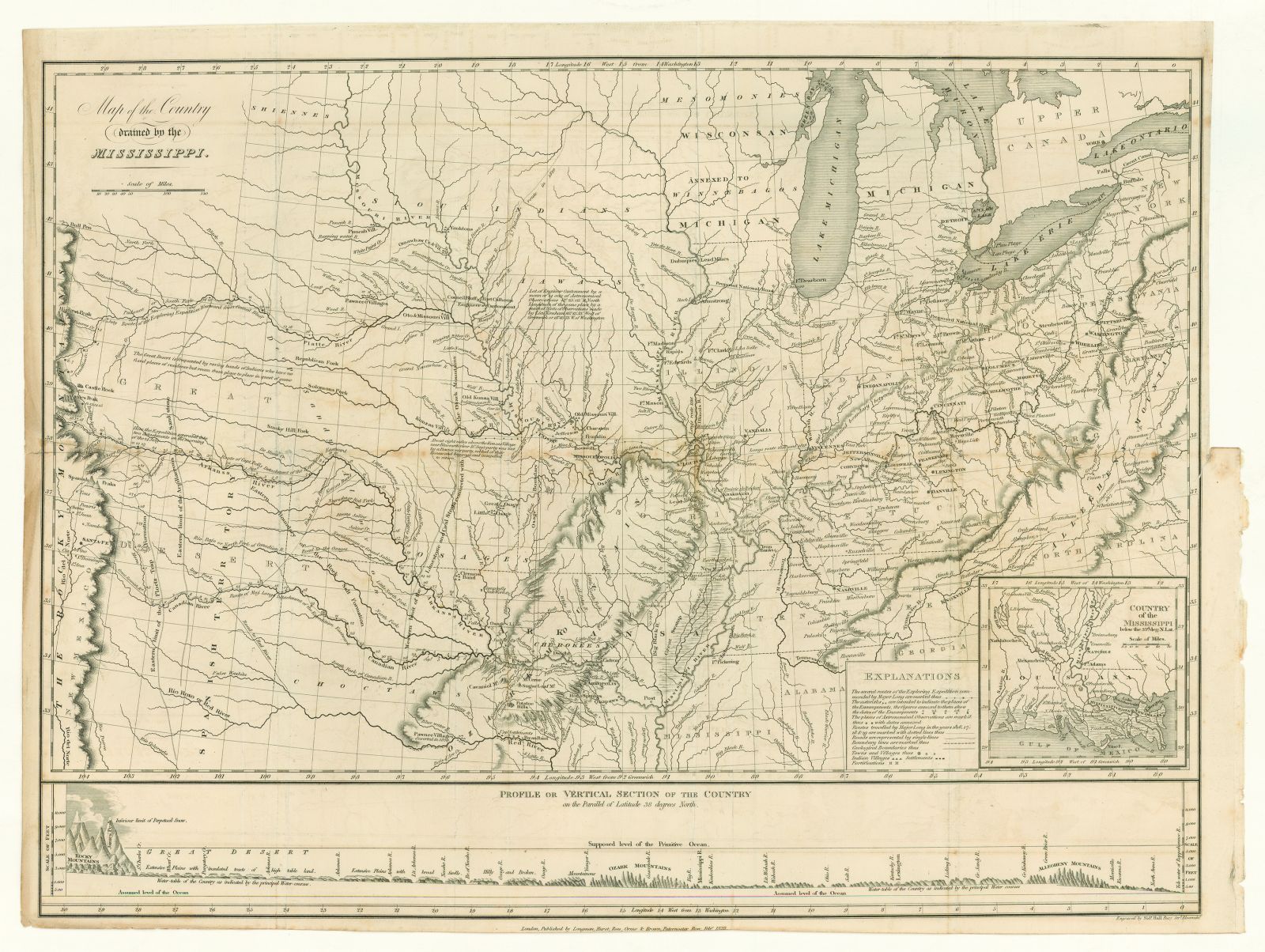

Edwin James (1797–1861)

“Map of the Country Drained by

the Mississippi,” in “Account of an Expedition from

Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains … under the Command of

Major Stephen H. Long ...”

London, [1823]. Printed map,

16 x 21 inches. Courtesy of

Barry MacLean Collection.

Maj. Stephen H. Long’s scientific expedition (1819–1820)

continued the tradition of U.S. Army-sponsored exploration.

The expedition culminated in a published narrative with a map

that delineated Long’s route from St. Louis up the Missouri

and Platte Rivers to the Rocky Mountains. Information for the

eastern half of the map was borrowed from commercial sources,

while the western half corrected geographical errors made by

previous expeditions. However, Long incorrectly characterized

the High Plains as the “Great American Desert” (see

southwestern quarter of map). This misconception may have

deterred Euro-American settlement of the Great Plains during

the early and mid-19th century.

Edwin James (1797–1861)

“Indian Record of a Battle

between the Pawnees and the Konzas. A Facsimile of a

Delineation upon a Bison Robe,” in “Account of an Expedition

from Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains …”

London,

[1823]. Print, 6 x 7.5 inches. Courtesy of

David Rumsey Collection. Reproduction, 2019.

Rather than relying on Native knowledge, Long’s party included

scientists and artists for the first time. Although artist

Samuel Seymour drafted more than 150 sketches, the report

published only eight, which documented landscapes and

encounters with Native people. The final and most unique plate

reproduced a buffalo robe showing a battle between Pawnee and

Kansa (Kansas) warriors. The design provides a contrast with

Euro-American methods of recording events in time and space,

depicting the spatial interrelationships of individuals drawn

in profile to record the conflict.

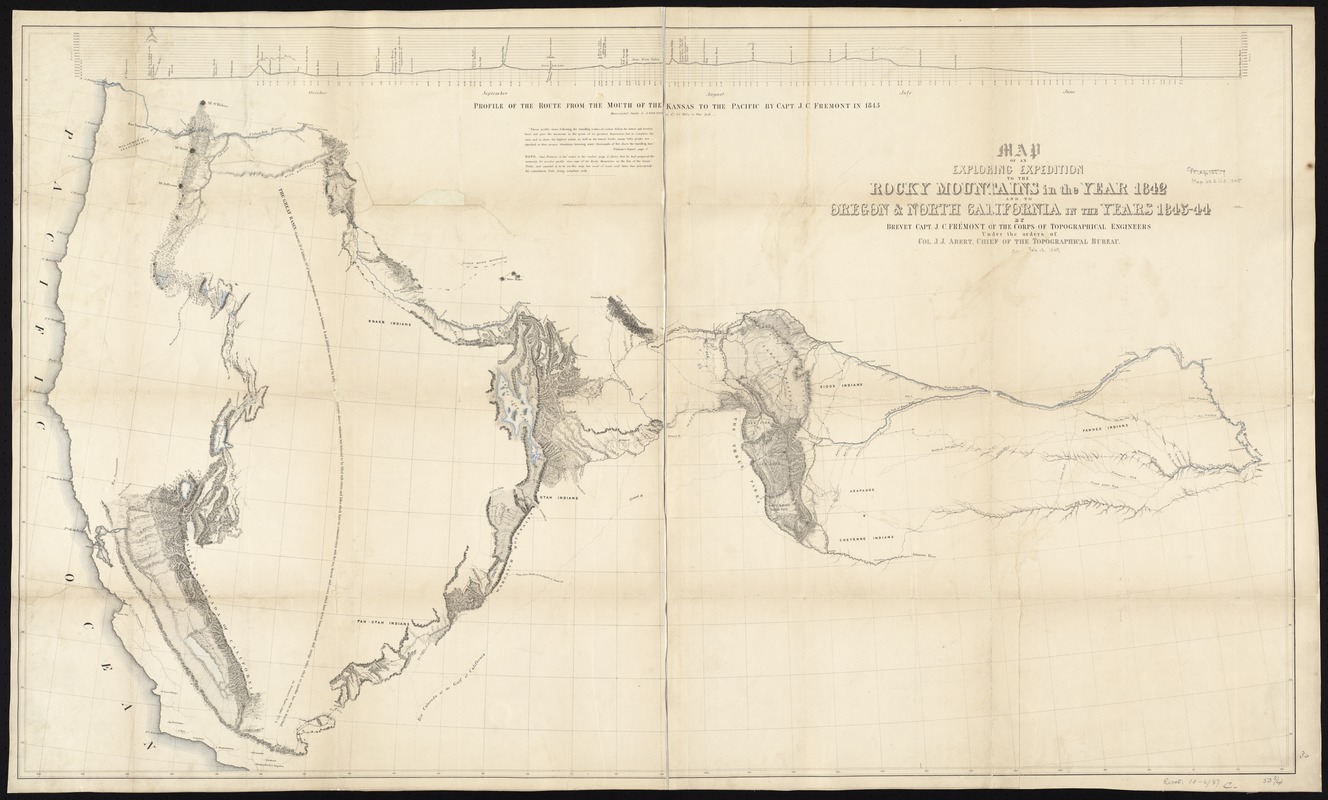

John C. Frémont (1813–1890)

“Map of an Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains … and

to Oregon & North California …”

Washington, DC,

1845. Printed map, 59 x 66 inches. Leventhal Map and

Education Center.

During the 1840s, Americans became interested in the Far West

as they settled the Oregon Territory and entered the

Mexican-American War. One American explorer who made major

contributions during this period was John C. Frémont, who led

five scientific expeditions. Charles Preuss, a German

immigrant and the expedition’s cartographer, prepared this map

depicting only the geographic information collected. Frémont’s

official reports, written with the assistance of his wife

Jessie (daughter of expansionist-minded Missouri senator

Thomas Hart Benton), gave “manifest destiny” a popular text.

Advocates of “manifest destiny” believed it was the nation’s

mission and preordained right to spread American institutions

and culture, thus justifying a policy of territorial

expansion.

John Disturnell (1801–1877)

“Mapa de los Estados

Unidos de Méjico”

New York, 1846. Printed map, 30 x 37

inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

Published a year after the annexation of Texas, at the outbreak of the Mexican-American War, this map depicts the northern region of Mexico (today part of the United States). It reveals a cultural landscape with both Spanish and Native settlements. Besides the Spanish settlements in southeastern Texas, there were three other clusters in this northern region – the upper Rio Grande (New Mexico), southern Arizona, and the California coast. While some Spanish settlements had been established more than a century earlier, Spanish culture was imposed on numerous Native groups already living in the area including the Pueblo, Numunu (Comanche), N’Dee (Apache), Hopitushínumu (Hopi), and Diné (Navajo).

VIEWPOINT: This map offers a great example of the fluidity of geography, as we can see how its meaning had shifted and would shift again. Lost in the designs of nation-states are the numerous indigenous geographies (still visible in maps like this) that remain in place and persist to this day.

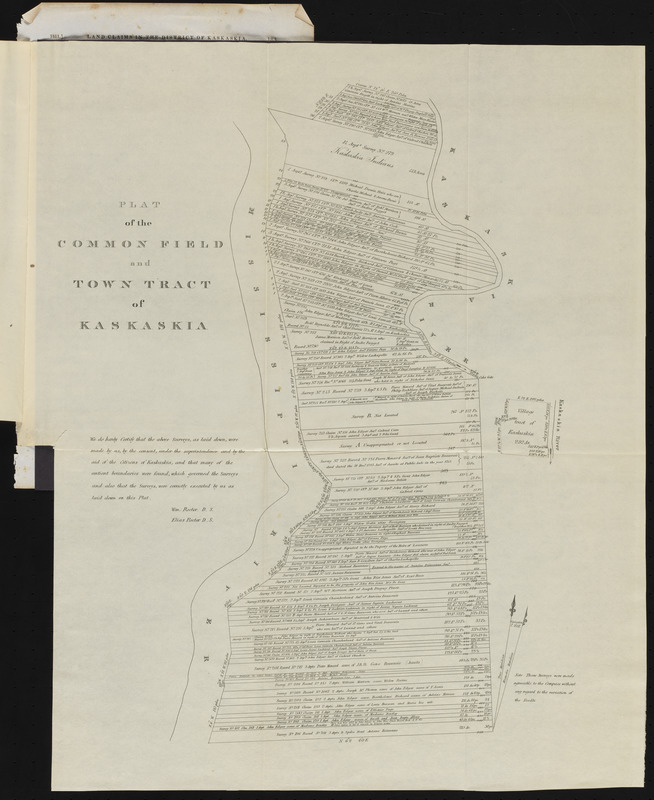

William Rector (1778–1827) and Elias Rector (d. 1822)

“Plat

of the Common Field and Town Tract of Kaskaskia”

Washington,

DC, 1807. Printed map and report, 20 x 17. Courtesy of

Lawrence Caldwell. Reproduction, 2019.

U.S. officials agreed to adjudicate land grants, known as

private land claims, that had been made by French, British,

Spanish and Mexican governments to their settlers. The first

of these transactions were for early French settlements, such

as the village of Kaskaskia shown here, later named the

capital of the Territory of Illinois. On this map, the Common

Field is divided into long narrow lots, a common

characteristic of French settlements. These irregular surveys

were incorporated into the rectangular grid pattern.

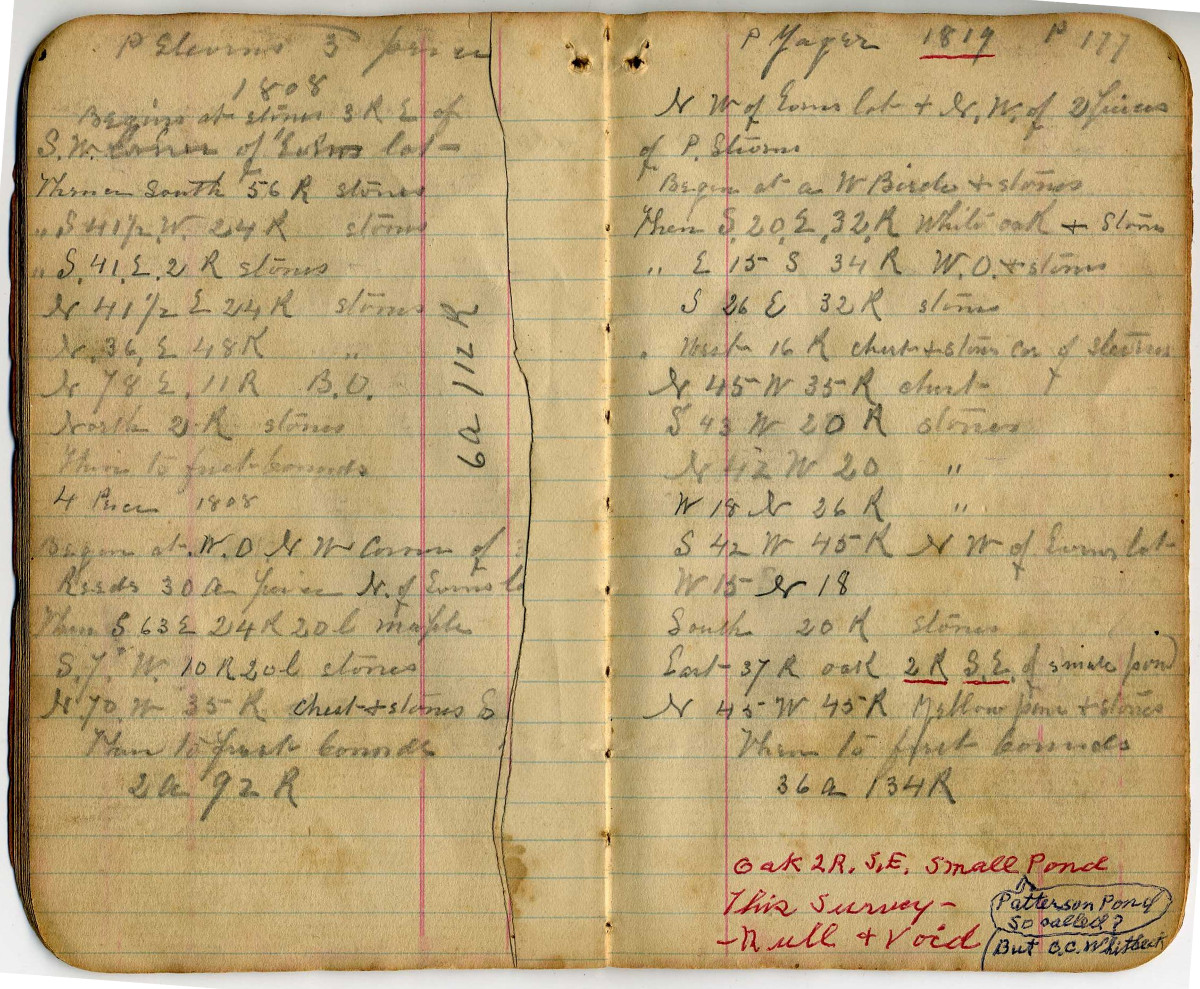

Horace Minot Pool (1803–1878)

“Surveyor’s Compass,

Chain and Chain Pins, and Field Notes”

Easton, MA,

1841-1878. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

Surveyors determined angles or direction in simple cadastral

or property surveys using a compass, like this one made in

Easton, Massachusetts. They measured distance with an

iron-link chain of 100 links or 66 feet, using a unit called a

pole or rod which equaled 16.5 feet. An example of surveyor’s

field notes documenting the “metes and bounds” of a survey

opens with “Begin at a W. Birch and stones, then S 20 E 32 R.

White oak and stones.”

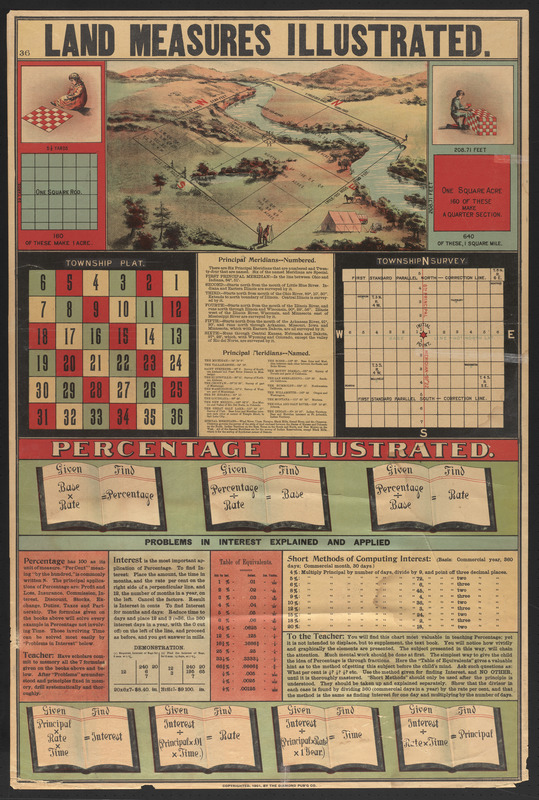

Diamond Publishing Co.

“Land Measures Illustrated”

Minneapolis, 1901. Broadside, 41 x 27.5 inches.

Leventhal Map and Education Center.

This educational poster illustrates the structure of General

Land Office township surveys. The top scene depicts surveyors

laying out a single section, measuring one mile by one mile

and containing 640 acres. The diagram labeled “Township Plat”

demonstrates the division of a township into 36 sections,

while the “Township Survey” diagram explains that townships

are identified in relation to a base line and meridian

(representing an X-Y axis). Each parcel of land has a unique

numerical identifier such as the 40-acre tract where the

surveyors stand could be identified as the SE 1/4 of the SE

1/4 of Section 1, Township 3 North, Range 4 West, 6th

Principal Meridian.

VIEWPOINT: These divisions remind us of the harmful game of wrongful land dispossession. For Native people, these squares represent a systematic disruption of our ancestral ways of life. This diagram reflects the colonial concept of land ownership: packaged up in little squares, as though one can compartmentalize a way of life and sell it.

William Dall (fl. 1800)

“Map of W. Dall's Lots in

Athens County, Washington County, and Gallia County,

Ohio”

1800. Manuscript map, 8 x 10 inches. Leventhal

Map and Education Center.

This small manuscript map served as a personal record of one

individual’s land holdings. It highlights the grid pattern

that was characteristic of public land surveys initiated by

the Land Ordinance of 1785. These townships were part of the

Ohio Company’s purchases in southeastern Ohio. This private

land company, composed of Boston investors, established

Marietta as the first Euro-American settlement in the

Northwest Territory. The map noted that William Dall owned

five parcels of land in four townships, totaling over 900

acres.

William Woodruff (fl. 1817–1833), after Alexander Bourne

(1786–1849) and Benjamin Hough

“A Map of the State of

Ohio from Actual Survey”

Cincinnati, 1831. Printed map,

51 x 48 inches. Courtesy of Lawrence Caldwell.

Ohio, the 17th state, was the first carved out of the

Northwest Territory. Survey grid patterns based on 5- and

6-mile square townships were first implemented here, in

addition to traditional irregular metes and bounds surveys in

the Virginia Military District. To administer surveying and

sales, over a dozen private land companies, military land

districts, and congressionally-authorized districts were

created. By 1832 when this large wall map was updated,

surveying had been completed. County boundaries and township

perimeters are marked. The cartouche promotes agriculture and

river transportation with a scene of a farm overlooking the

Ohio River.

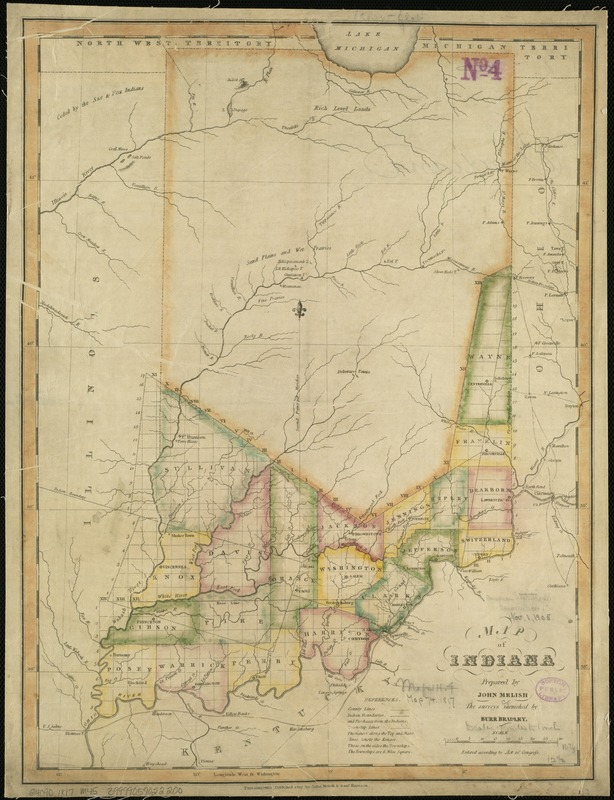

John Melish (1771–1822) and Burr Bradley

“Map of

Indiana”

Philadelphia, 1817. Printed map, 18 x 13.5

inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

Indiana Territory (“Land of Indians”) was similarly carved out

of the Northwest Territory in 1800. Published in 1817, a year

after Indiana’s statehood, this map indicates that officials

had divided the southern third of the state into counties and

townships. Numerous tribal nations, including the Myaamiaki

(Miami), Kiikaapoi (Kickapoo), Lenape (Delaware), Shawnee, and

Neshnabé (Potawatomi) inhabited the region. The map identifies

land cessions before 1817 with dashed lines. From the 1820s

through the 1840s these tribal communities were forcibly

relocated, most often to reservations in the Great Plains or

to Canada.

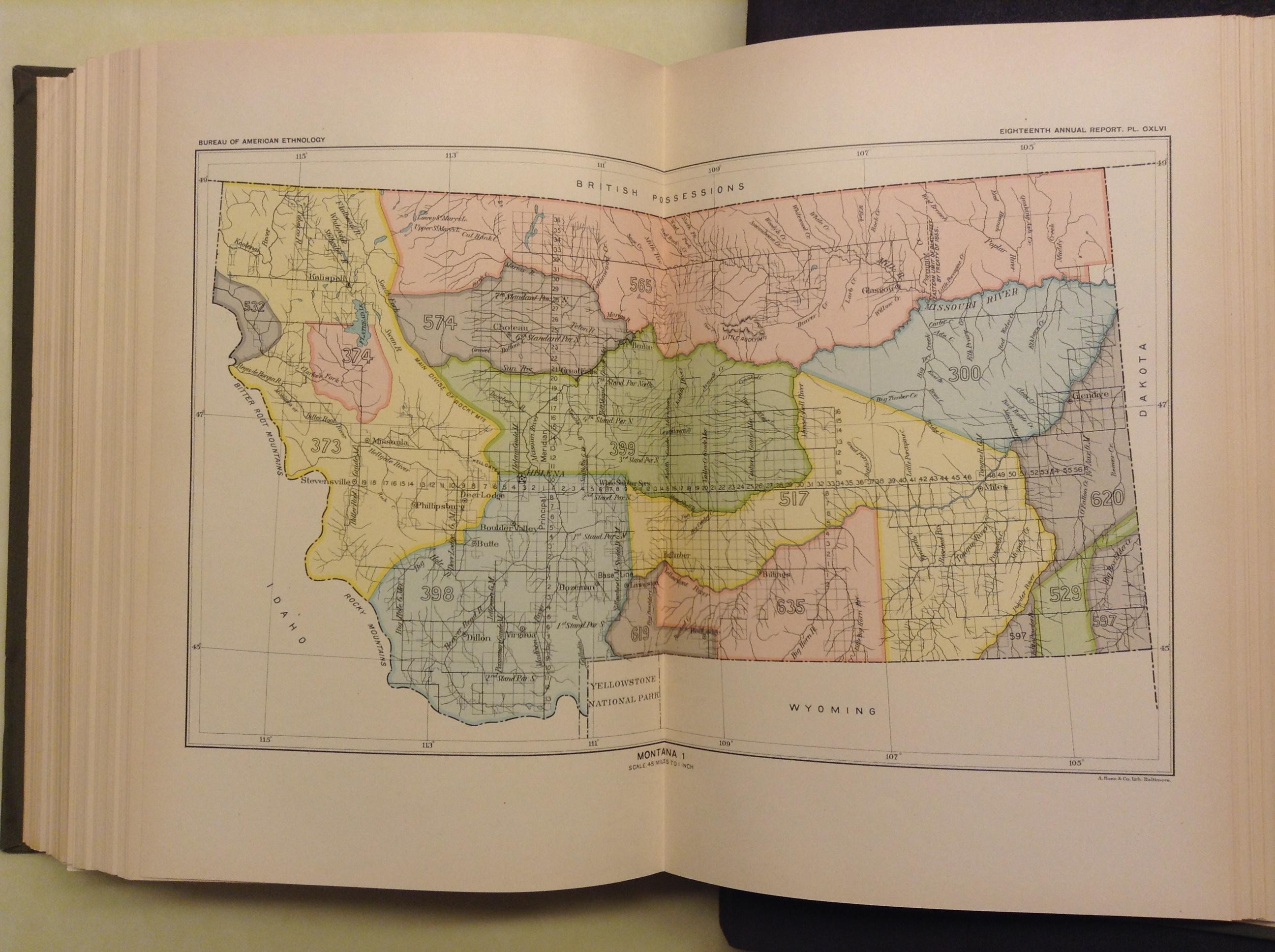

Charles C. Royce (1845–1923)

“Montana 1,” from “Indian

Land Cessions in the United States, 1784-1984”

Washington,

DC, 1899. Printed map, 11.5 x 14.5 inches. Courtesy of

Ronald Grim.

By the 1890s, the U.S. government seized over 1.5 billion

acres of Native land by way of treaty, coercion, military

force, and executive order. Tables in this compendium itemize

over 700 land cessions and treaties enacted between 1784 and

1894, while 67 maps delineate the boundaries of each

transaction. For example, the yellow and pink districts in

western Montana (numbered 373 and 374) refer to the 1855

Treaty of Hellgate, negotiated with the Séliš (Flathead),

Kootenai (Kootenay), and Q'Lispé (Upper Pend d’Orielles).

Through a contentious negotiation process mired in

mistranslation and differing expectations, the tribes ceded

their lands and became dissatisfied with enforcement of the

treaties. Hostilities broke out in 1858.

VIEWPOINT: “Cede” is a very gentle term to describe a deeply violent, forced, and uneasy process. As Native groups suffered losses from epidemics and the destruction of their food sources, they relinquished their lands to the U.S. government, often as a final resort. Native groups were forced to relocate from their homelands, either by treaty or executive orders promising them abundant resources in exchange for territory – none of which were fully realized.

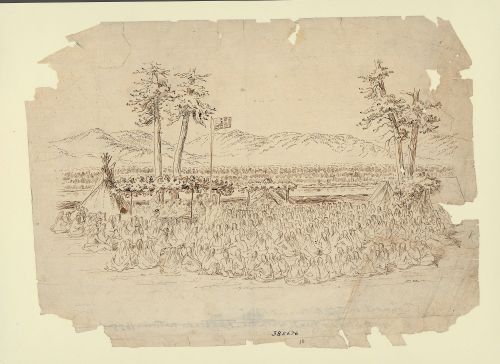

Gustavus Sohon (1825–1903)

“Feast for the Indian

Council”

1853. Manuscript pencil drawing, 8 x 10

inches. Courtesy of

Smithsonian Institution National Anthropological

Archives. Reproduction, 2019.

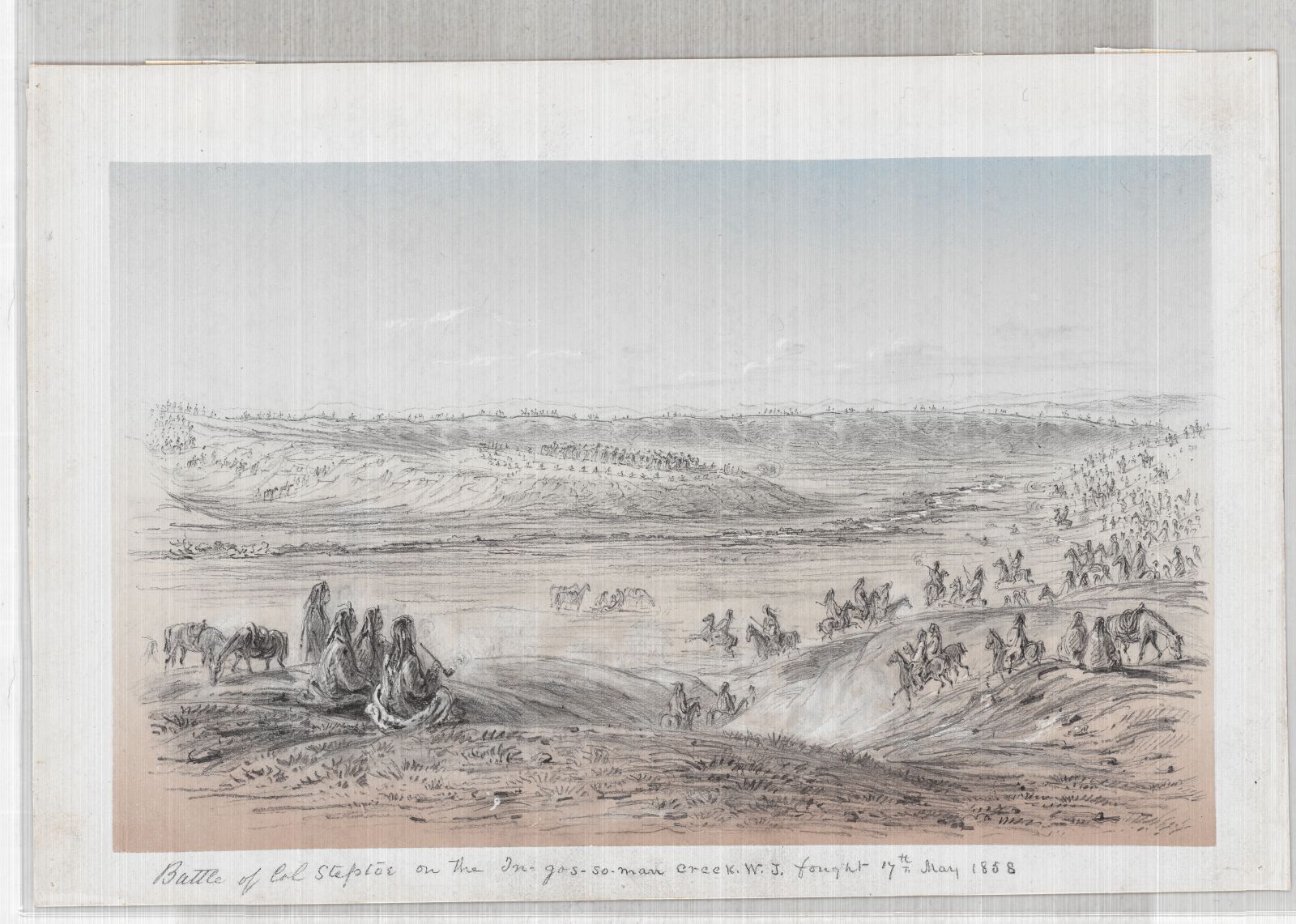

Gustavus Sohon (1825–1903)

“Battle of Col. Steptoe on the In-gos-so-man Creek,

W.T., Fought 17th May 1858”

1858. Manuscript pencil drawing, 6.75 x 10 inches.

Courtesy of

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs

Division,

LOT 2528 (F) [P&P]. Reproduction, 2019.

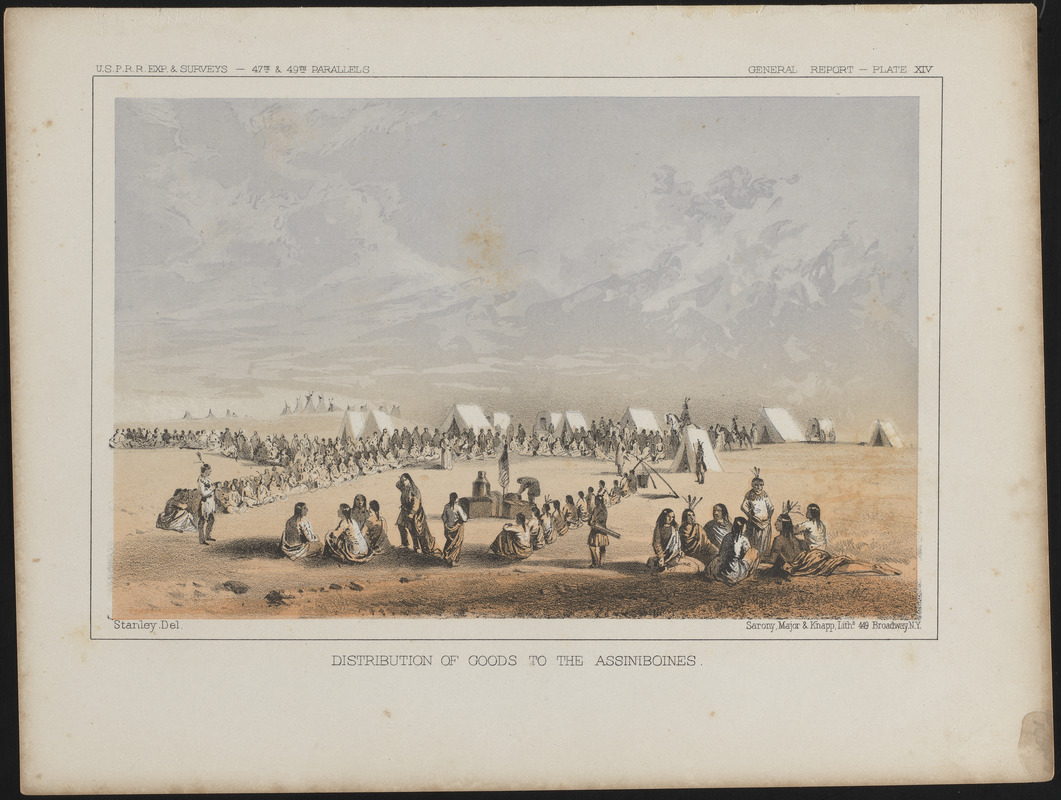

Isaac Stevens, leader of the Northern Pacific Railroad Survey

and Washington’s territorial governor, negotiated several

treaties during the 1850s to help justify the construction of

a northern railroad route and to entice Americans to move to

the Pacific Northwest. Two pencil sketches, prepared by

Gustavus Sohon, a German immigrant who served as an artist and

interpreter with Stevens, depict scenes from this period. In

1855, he produced this pencil drawing documenting Stevens’

negotiation with the Flathead Treaty Council. In 1858, he

accompanied the campaign against the Spokane, Schitsu'umsh

(Coeur d'Alene), and Palouse. His second drawing records the

defeat of U.S. Army troops by a combined force of several

Native groups.

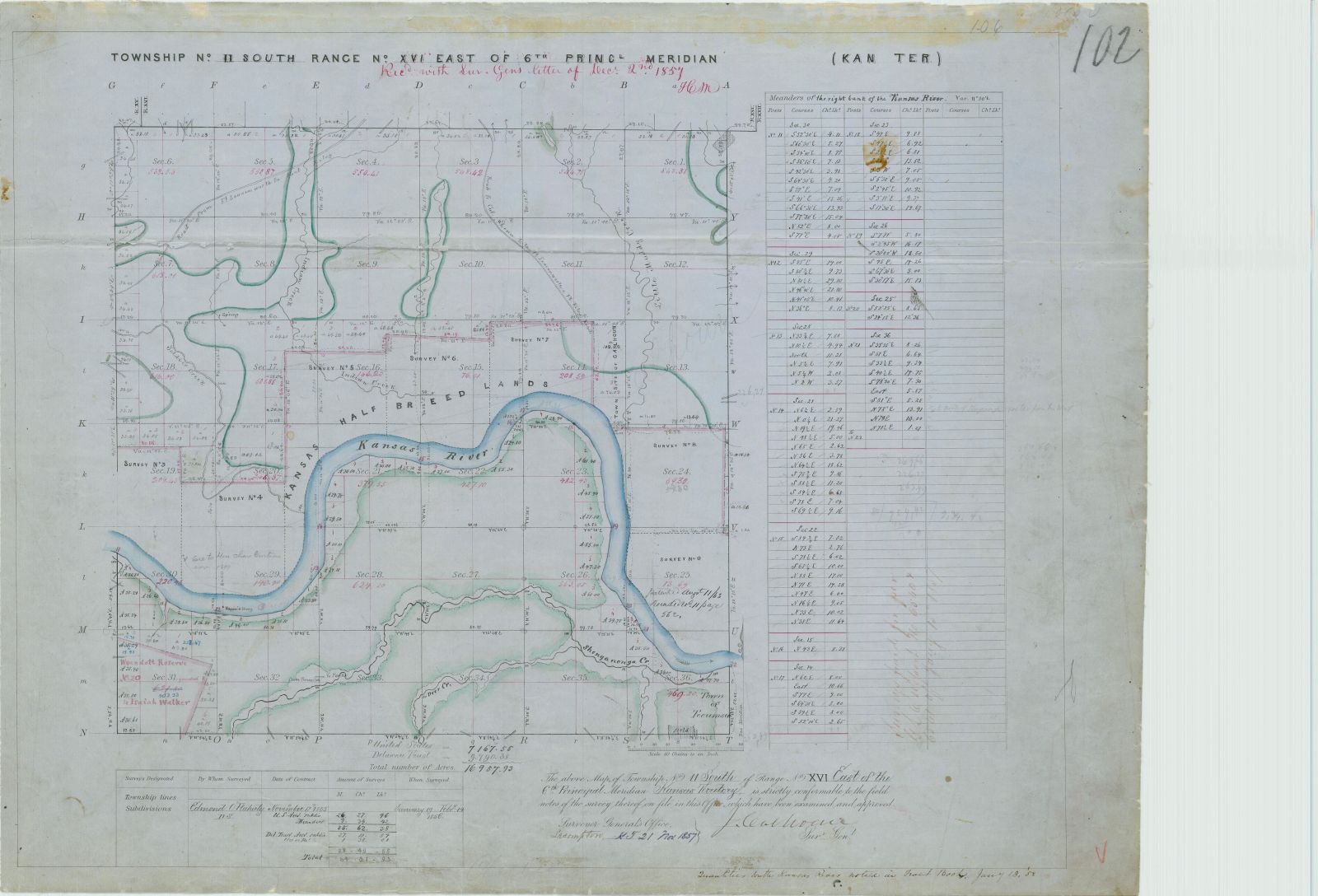

John Calhoun (1806–1859)

“Township no. 11 South, Range

no. XVI East of 6th Princl. Meridian”

1857. Manuscript

survey plat, 17 x 22 inches. Courtesy of

National Archives and Records Administration,

Record Group 49, Kansas Headquarter Plats. Reproduction, 2019.

The General Land Office produced manuscript survey plats for

each individual township. Their primary purpose was to outline

the boundaries of the six-mile square township and each of the

36 sections. Surveyors often noted natural and man-made

features that crossed or were near the surveyed lines. In this

Kansas example, the Kansas River and tributary streams

dominated the landscape. Green lines marked the boundary

between woodland and prairie, while existing roads,

farmsteads, and town sites were also mapped. One unusual

feature is seven 640-acre tracts, identified as Kansas

half-breed lands, which were allotted to individuals of mixed

Kaw (Kanza) and European ancestry.

VIEWPOINT: Full breed lands did not exist because full breeds were not considered human enough to be land owners. Half breeds, or mixed race Natives were considered to be partially human and able to own land, while Natives with no European ancestry were less than human, not worthy of land possession.

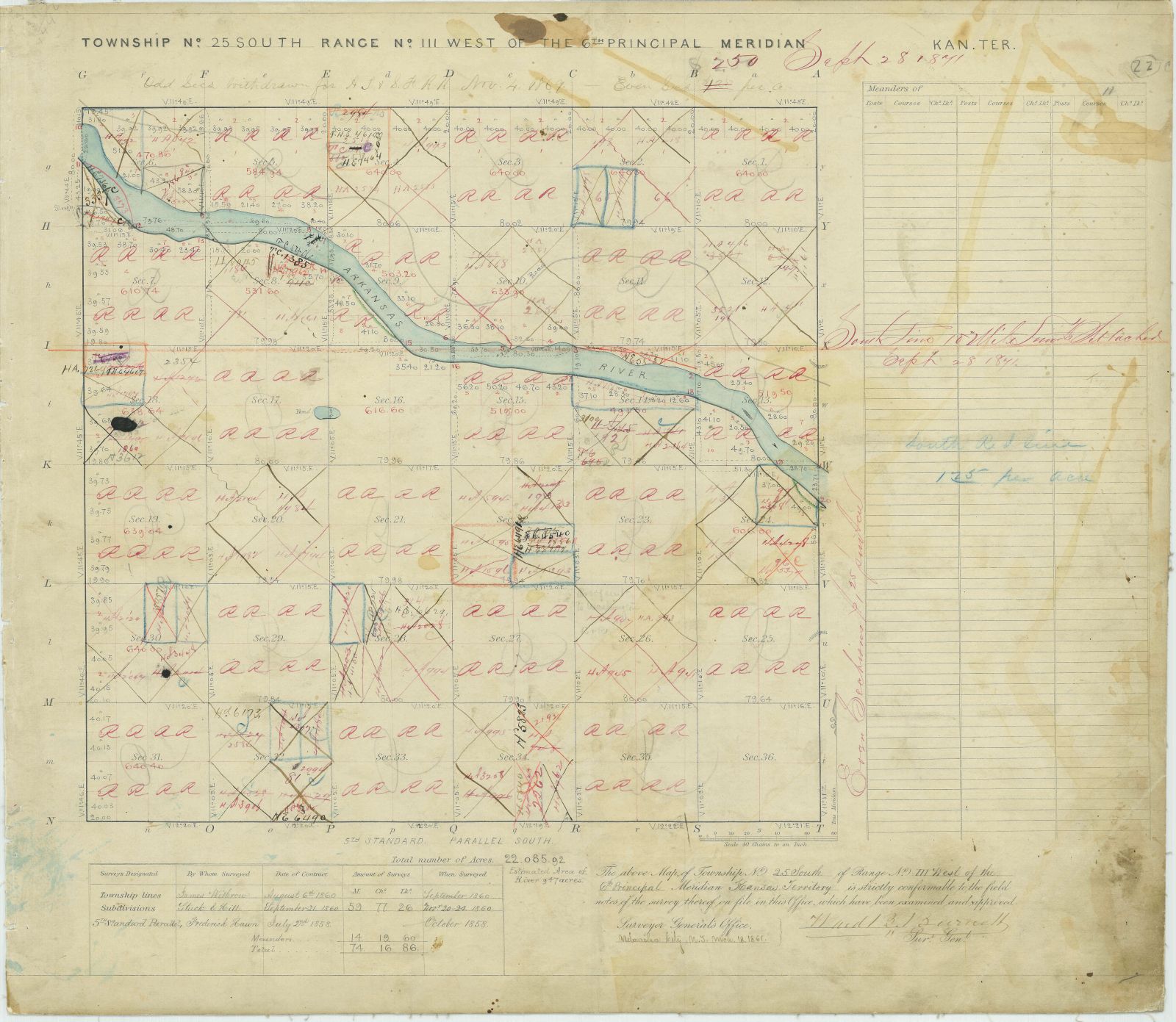

Ward Burnett (1811–1884)

“Township no. 25 South, Range

no. III West of the 6th Principal Meridian”

1861, with

later annotations. Manuscript survey plat, 16.5 x 19 inches.

Courtesy of the

National Archives and Records Administration,

Record Group 49, Kansas Local Office Plats. Reproduction, 2019.

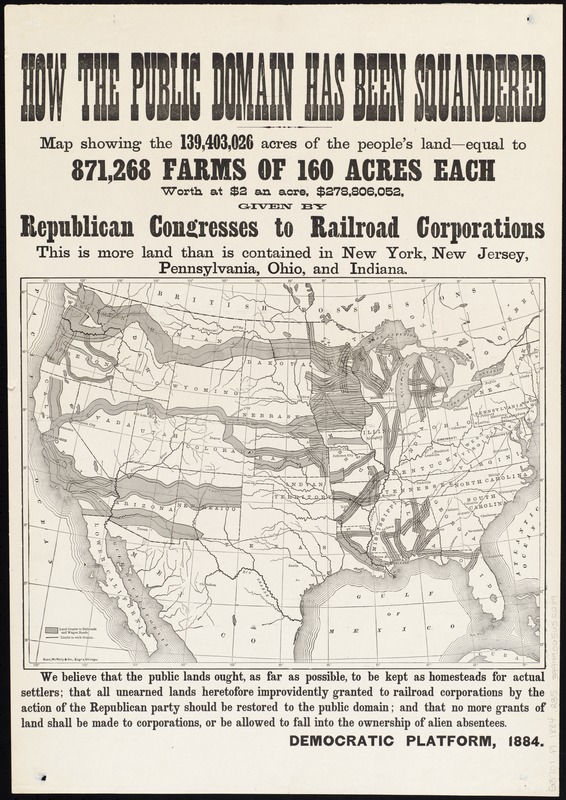

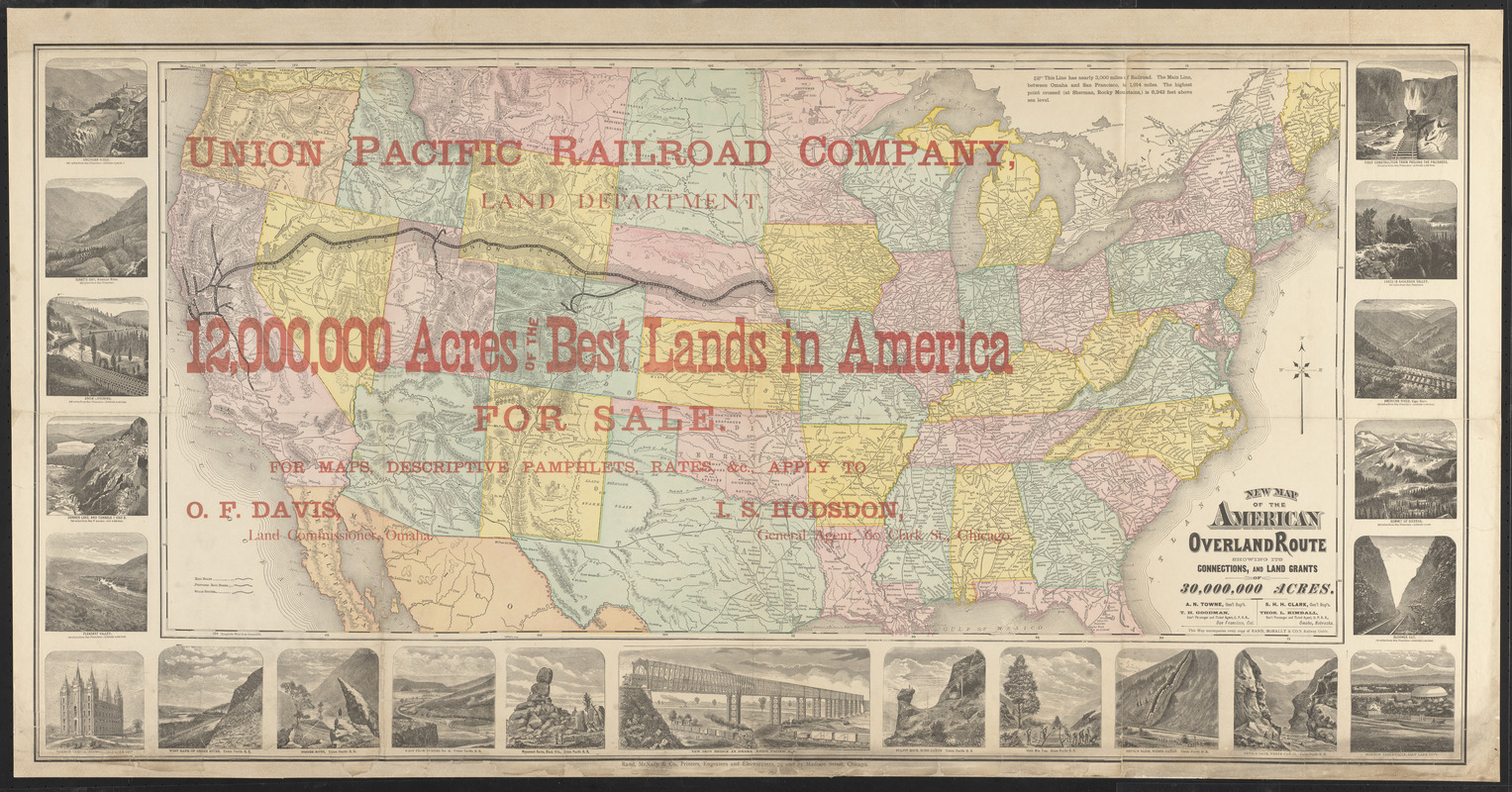

The Homestead and Pacific Railroad Acts, both passed in 1862,

dramatically changed the process for granting public lands.

The former allotted 160 acres to white settlers, as well as

freed men and women, who would improve land within five years

of selection. The latter authorized construction of the first

transcontinental railroad and established the principle of

giving alternating sections (640 acres) to railroad companies.

For example, this township was surveyed in the late 1850s, but

most of the land was not selected until the 1870s. Alternating

sections marked with “RR” were granted to a railroad company,

while those sections patented through the homesteading process

are indicated by an X.

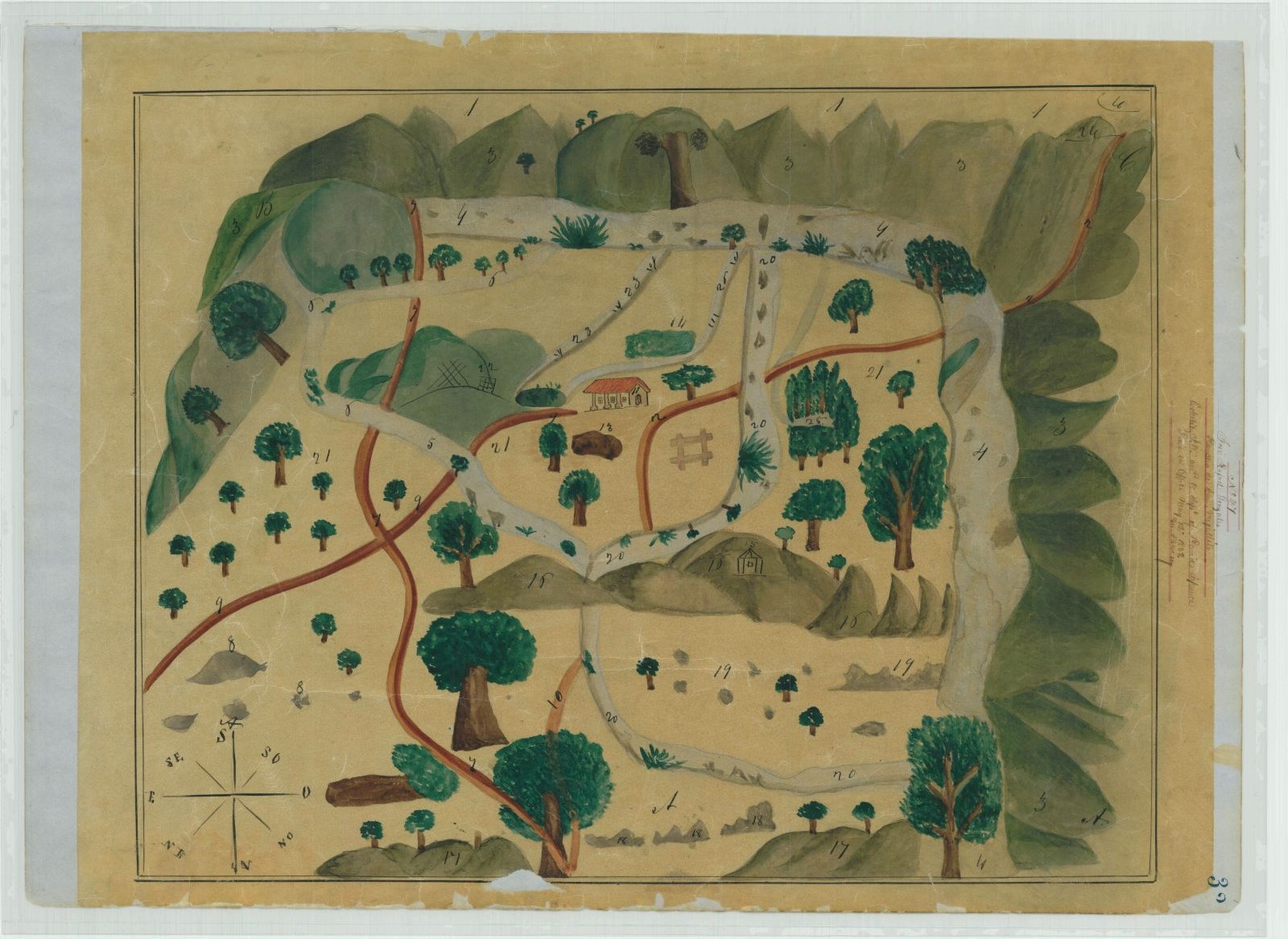

José Rafael Gonzales (fl. 1852)

“Diseño for Rancho San

Miguelito”

1852. Manuscript drawing, 12 x 17 inches.

Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration,

Record Group 49, California Private Land Claims, Diseños. Reproduction,

2019.

The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the

Mexican-American War and ceded much of this southwestern

territory to the United States. The federal government agreed

to honor Spanish and Mexican land grants. Claimants in

California had to submit a documentary case file

(expediente) with a description and map (diseño)

of the tract. Displayed here is a diseño for more than 22,000

acres granted by the Mexican governor in 1841 and finally

approved by the U.S. government in 1867.

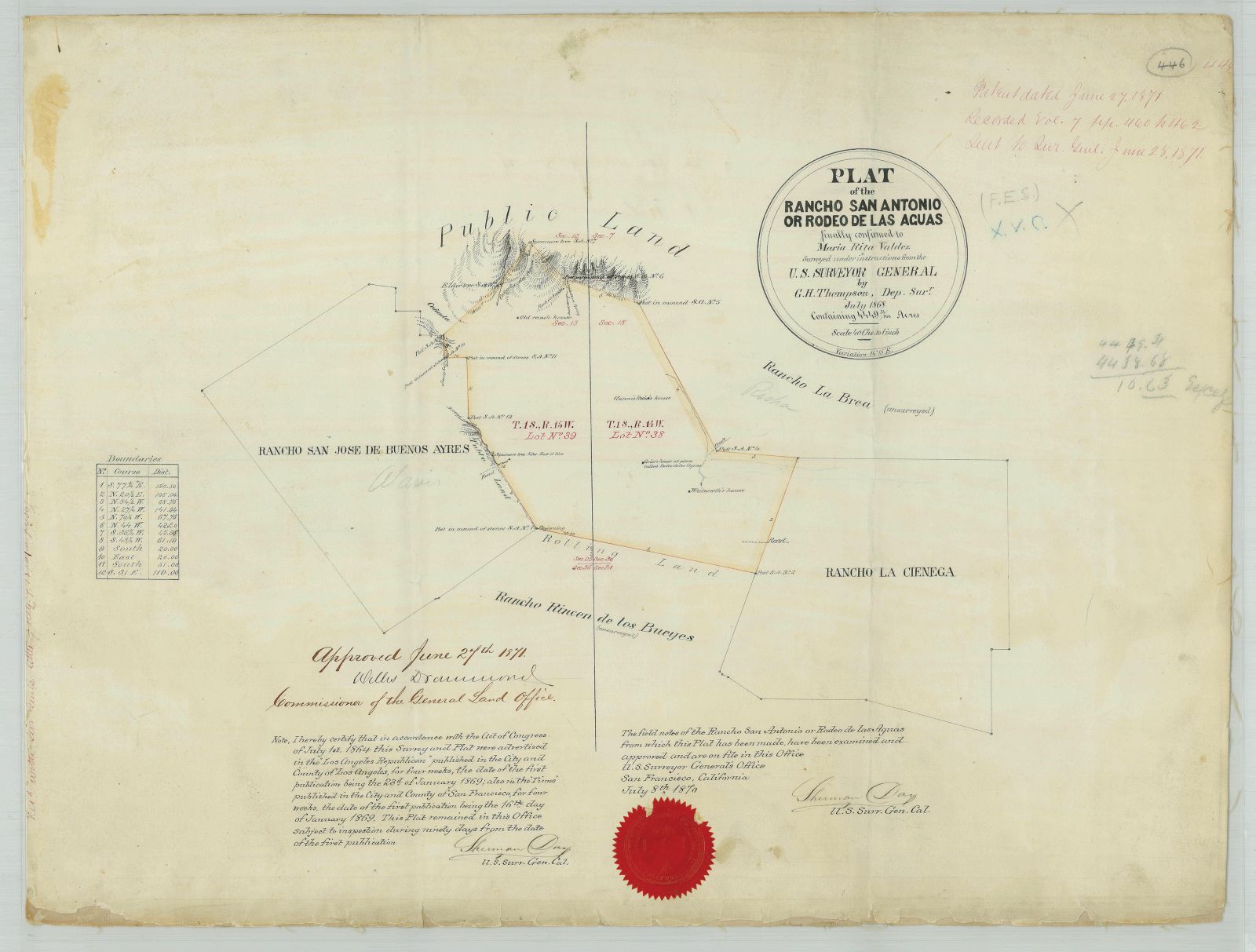

George H. Thompson (fl. 1870)

“Plat of the Rancho San

Antonio or Rodeo de las Aguas, Finally Confirmed to Maria

Rita Valdez”

1870. Manuscript survey plat, 19 x 25.5

inches. Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration,

Record Group 49, California Private Land Claims, Survey Plats.

Reproduction, 2019.

In California, Spanish settlements extended along the California coast from San Diego to San Francisco. Over 800 private land claims required adjudication, reflecting a variety of settlements identified as presidios (forts), pueblos (towns), missions, and ranchos. The latter were large land holdings that ranged from 4,000 to 40,000 acres and rarely had precise boundaries. Displayed here is the final survey for Rancho Rodeo de las Aguas, originally granted in 1838 to Maria Rita Valdez, a granddaughter of one of the original settlers of Los Angeles. The grant was finally surveyed and approved by the General Land Office in 1871, although she sold the property in 1854.

1b. LAND 1862-1900: Surveying and Conserving the Land

In the late eighteenth century, government explorers and surveyors initiated the settler-colonial process of westward expansion. In the 1780s, Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance to establish the process for admitting new states. The laws also outlined the principles for surveying and selling public lands that the United States had gained through purchase, trickery and obfuscation, warfare and other forms of violence, forced removal, and treaty. Surveyors standardized the practice of dividing land into six-mile square townships that provided the foundation for settlement patterns in western states. Government surveys noted the land claims of earlier French and Spanish inhabitants and aimed to prove the cession of lands occupied by Native tribes.

From 1803 to 1805, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark set out to inventory and map the newly acquired Louisiana Purchase. Their trip paved the way for similar expeditions and culminated in the 1850s with the Pacific Railroad Surveys, which mapped potential routes for the first Transcontinental Railroad. Each of these efforts brought back cartographic and scientific data about the inhabitants, landscape, natural resources, and wildlife. By the final third of the century, many Americans had become concerned about conserving these natural resources and landscapes that were rapidly disappearing through economic exploitation.

For Kids

After the Civil War, large numbers of

Americans raced west in search of land and riches. Native

nations and parts of the natural world, like forests and

bison, suffered great losses as a result. Trees became lumber

and the search for fossil fuels and precious metals scarred

the land. At the same time, some Americans supported the idea

of National Parks to preserve the West’s most dramatic

landscapes.

- Can you find maps and images in this section that tell a story about what was gained as Americans expanded across North America?

- Can you find maps and images that tell a story about what was lost?

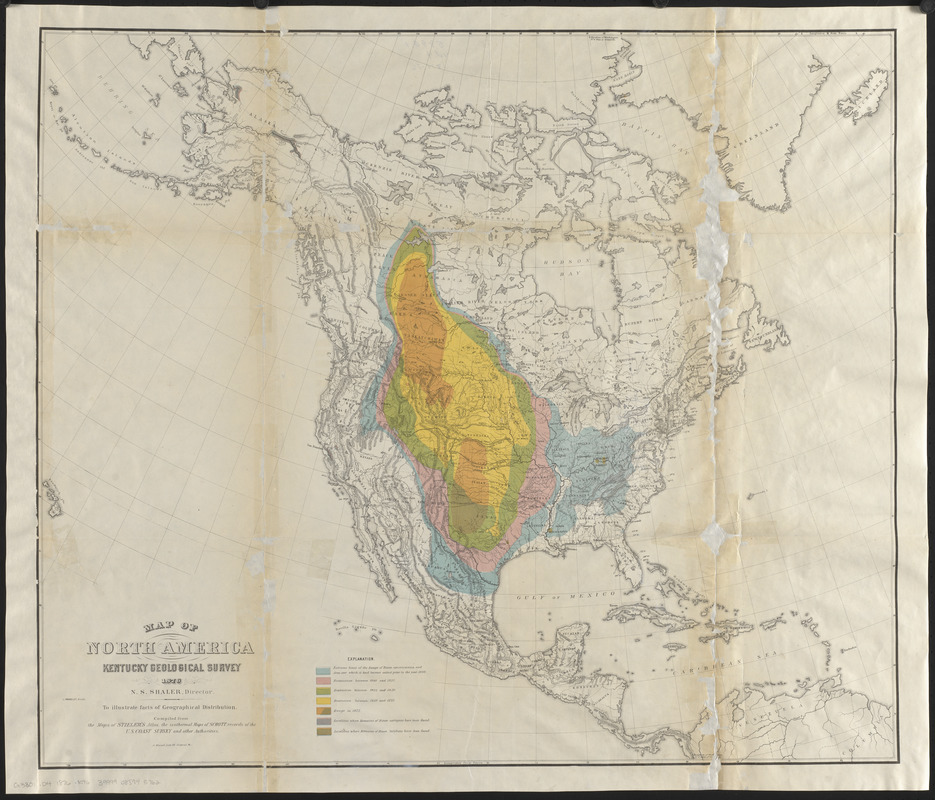

Joel A. Allen (1838-1921)

“Map of North America,”

from The American Bisons, Living and Extinct

Cambridge, MA, 1876. Printed map, 29.5 x 25 inches.

Leventhal Map and Education Center. Reproduction 2019.

This colorful map documents the diminishing range of bison

during the 18th and 19th centuries. It accompanied an 1876

report prepared by Joel Allen, an American zoologist,

mammalogist and ornithologist at Harvard’s Museum of

Comparative Zoology. The map shows the distribution of bison

before 1800 (blue), 1825 (pink), 1850 (green), 1875 (yellow)

and afterwards (orange). To emphasize the influence of

migration and railroad construction on bison, the map also

delineates the routes of the Emigrant Trail, the Union Pacific

Railroad, and other railroads in Kansas and Colorado.

Viewpoint: This map only shows trail and railroad construction, but those were not the major reasons for the demise of bison in the 19th century. Bison leather was in high demand — it was used by the government to make Army boots, and bison-leather belts powered the machines that created the industrial revolution. The leftover bones were shipped east by the new railroads in massive amounts to be made into china. The demise of bison led to forced land cessions by Native people as many tribes lost their food supply and trusted the treaties' false promises of food and supplies.

Stackpole & Brother [manufacturer]

Surveyor’s

transit, serial number 1332

New York, 1872. Gift

of Cornell University School of Civil and Environmental

Engineering.

Buff & Buff Manufacturing Co. [manufacturer]

Surveyor’s

Level

Boston. Gift of Cornell University School of Civil and Environmental

Engineering.

Surveyor’s instruments, rather than guns, were possibly the

most influential weapons used in the European conquest and

colonization of the American landscape. These tools were used

to establish administrative boundaries, delineate property

lines, lay out towns, determine transportation routes, and map

topography. This transit, which measures horizontal angles to

a highly precise degree of accuracy, was used in the

engineering school at Cornell University, New York’s “land

grant” college established under the terms of the 1862 Morrill

Act, which granted federal land to each state to establish

agricultural and scientific universities. Surveying was a

practical course for the civil engineers who would go on to

map the nation and build its infrastructure.

William H. Brewer (1828-1910)

"Map Showing in Five

Degrees of Density the Distribution of Woodland within the

Territory of the United States, 1873." in

Statistical Atlas of the United States …

Washington, D.C., 1874. Printed map, 22 x 33 inches.

Leventhal Map and Education Center.

Reflecting growing concerns for the nation’s diminishing

natural resources as a result of individual ownership and

overconsumption during the first half of the 19th century,

this statistical map depicts forest density at the time of the

1870 census. The most extensive woodlands were in the East,

along the northern Pacific Coast, and in the northern Rocky

Mountains. Outside these forested areas were the grasslands of

the Great Plains and the semi-arid scrub lands of the

Southwest. Much of the East, which was originally very heavily

forested, had less than 20-35 percent of the acreage in

woodland after extensive deforestation.

Thomas Hill (1829-1908)

Yosemite Valley

Boston: Louis Prang and Co., 1861-1897.

Chromolithograph. Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Print Department. Reproduction 2019.

This chromolithographic print of Yosemite Valley not only

provides an example of the remaining forests found in the

Rocky and Pacific Coast mountains, but it also captures the

drama of Western landscapes. Light shines onto a fertile

valley framed by sheer mountain cliffs accentuated by a

waterfall. Louis Prang, who immigrated to Boston from Prussia,

published such popular, colorful prints, which reinforced the

idea that the West was a largely uninhabited, wild, unique

landscape.

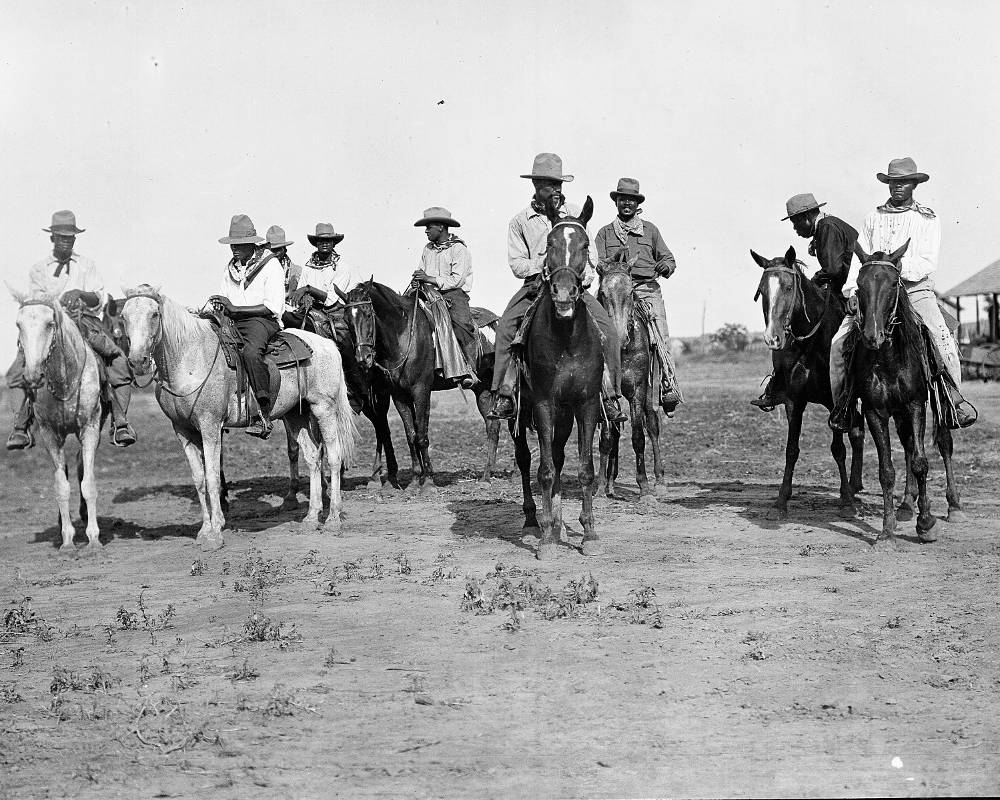

Negro Troopers of 1899 [Buffalo Soldiers] [24th

Infantry].

Film, 5 x 7 inches. Courtesy of

U.S. National Park Service. Reproduction 2019.

At the end of the Civil War, black troops enlisted into U.S.

forces, both former Union soldiers and new recruits. Known as

buffalo soldiers and consolidated into two cavalry and two

infantry regiments, these men fought against Native people and

the Mexican resistance as they provided security to settlers

moving westward. They also participated in the U.S. war

against Spain in Cuba and against Spain and the Filipino

resistance in the Philippines. Starting in 1899, soldiers of

the 9th Cavalry and 24th Infantry spent summers as the first

park rangers in two of the nation’s earliest national parks,

Yosemite and Sequoia.

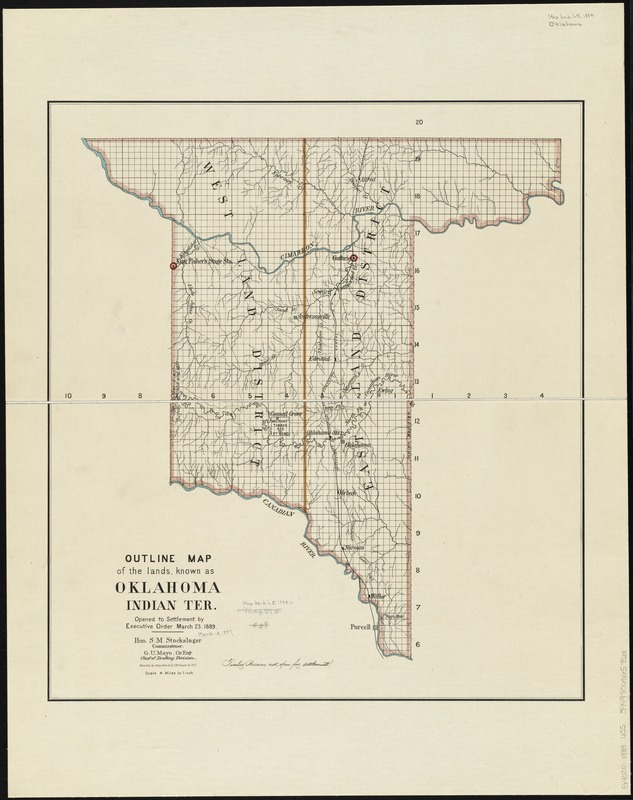

U.S. General Land Office

Outline Map of the Lands Known as Oklahoma, Indian Ter.,

Opened to Settlement …

Washington, D.C., 1889. Printed map, 24 x 21.5

inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 allocated the eastern portion

of today’s Oklahoma for the Chahta (Choctaw), Chikasha

(Chickasaw), Mvskoke (Creek), Semvnole (Seminole), and Tsalagi

(Cherokee) and other eastern tribal nations. Following the

Civil War, the U.S. government assigned much of western

Oklahoma to tribes living on the Great Plains and further

west. When President Benjamin Harrison took office in 1889, he

signed a proclamation opening 1.9 million acres of "Indian

territory" to non-Natives for homesteading. This map depicts

the territory made available for settlement on April 22, 1889.

That day, over 50,000 people raced to claim the best lands,

including lots in the emerging towns of Guthrie and Oklahoma

City.

Land Rush of 1889 and

Guthrie, Oklahoma Ave., May 10-89

1889.

Photographic prints. Courtesy of

Oklahoma Historical Society. Reproductions 2019.

Two photographs illustrate Americans’ eagerness to participate

in this land rush. The first records the mass (and blur) of

people riding horses and driving wagons to stake their claims.

They quickly constructed towns and buildings to meet the terms

of the Homestead Act, which required settlers to erect

permanent dwellings. The other photograph illustrates the

growth of Guthrie, depicting Oklahoma Avenue after only three

weeks. Guthrie served as the local land office, and in 1890 it

was designated the territorial capital. Three years after

Oklahoma’s statehood in 1907, the government moved the capital

to Oklahoma City, a growing area at the juncture of major

railroads and home to a burgeoning meatpacking industry.

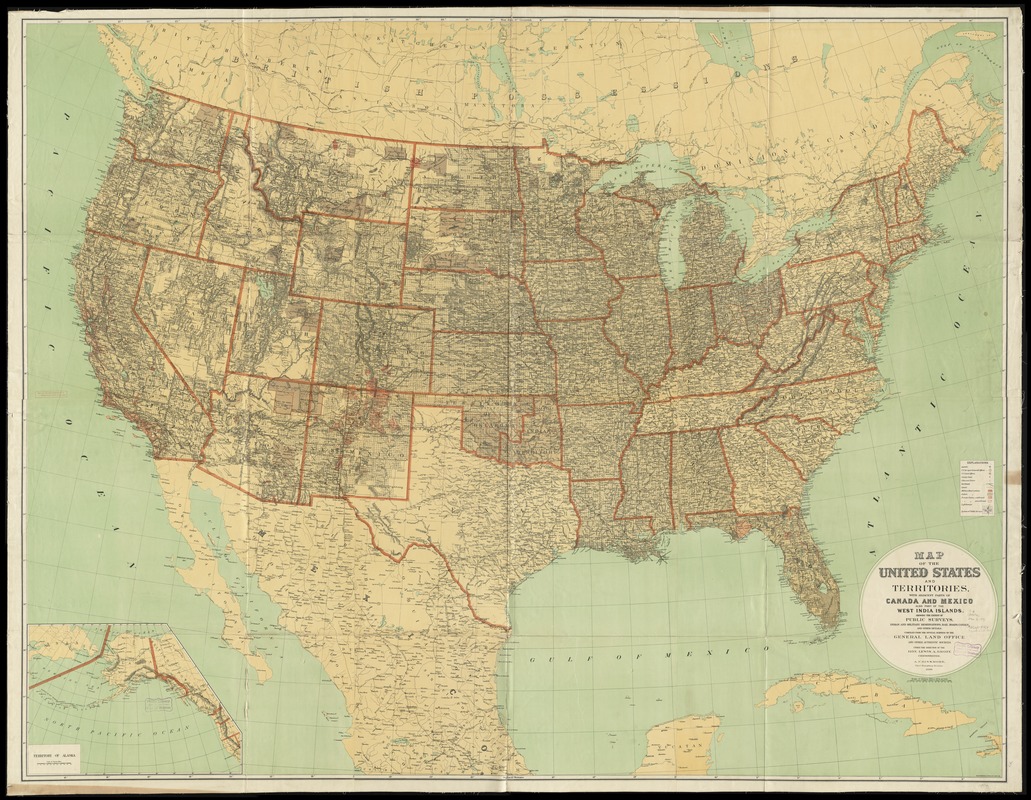

U.S. General Land Office

Map of the United States and Territories … Showing the

Extent of Public Surveys …

Washington, D.C., 1890. Printed map, 67 x 80 inches.

Leventhal Map and Education Center. Reproduction 2019.

This map highlights the federal government’s impact on transforming the American landscape by the end of the 19th century. Designed primarily to show the extent of township surveys, it uses a black grid pattern to represent lands that had been surveyed and open to settlement, which included all or most of the area in the public land states. The map shows the extent of Indian reservations (solid grey), military reservations (solid pink), and private land claims (pink cross hatch or pink outline). The latter, which represent Spanish land grants adjudicated during the 19th century, are most prevalent in Florida, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado and California.

Viewpoint: As the U.S. government took over territory, it introduced the English concept of "land ownership" to lands that were never governed that way under Native stewardship. U.S. land acquisition literally meant that the land in question went from being perceived as "sustaining life" to "sustaining means or income.” It was a big change and it was harsh on Native people. This dynamic overturned the power structure. Systematically Native peoples' life ways and cultures came under threat. Loss of access to land meant loss of true freedom. This process of dispossession repeats itself over and over, forcing Native peoples to begin adopting a foreign way of life as a matter of survival.

Ward Burnett (1811-1884)

Township no. 25 South, Range no. III West of the 6th

Principal Meridian

1861, with later annotations. Manuscript survey plat,

16.5 x 19 inches. Courtesy of

National Archives and Records Administration, RG 49. Reproduction 2019.

The Homestead and Pacific Railroad Acts, both passed in 1862,

dramatically changed the process for granting public lands.

The former allotted 160 acres to white settlers, as well as

freed men and women, who would improve land within five years

of selection. The latter authorized construction of the first

transcontinental railroad and established the principle of

giving alternating sections (640 acres) to railroad companies.

For example, this township was surveyed in the late 1850s, but

most of the land was not selected until the 1870s. Alternating

sections marked with “RR” were granted to a railroad company,

while those sections patented through the homesteading process

are indicated by an X.

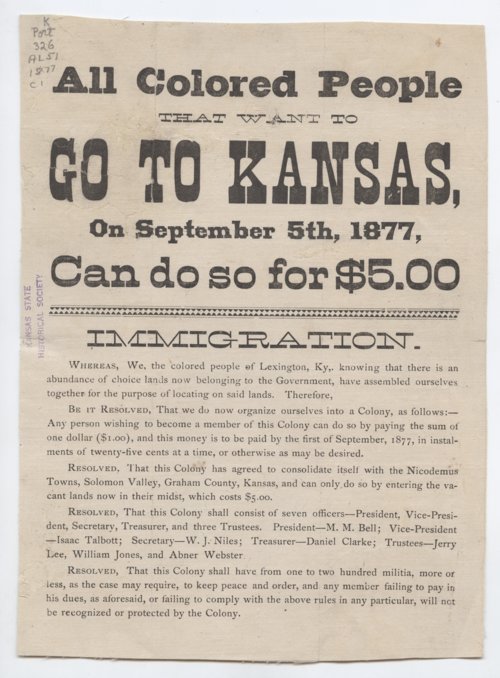

Nicodemus Town Company.

All Colored People that Want to Go to Kansas.

1877. Broadside, 10 x 7.5 inches. Courtesy of

kansasmemory.org,

Kansas State Historical Society, Copy and Reuse Restrictions

Apply. Reproduction 2019.

Following the post-Civil War Reconstruction period, African

Americans started to leave the South, migrating to northern

cities and Western states and territories. One destination was

Kansas, which was promoted in the 1870s through an organized

effort known as the Exodus. African American migrants were

told they would be moving to a “promised land,” and, as

depicted in this broadside, they were enticed with the

prospect of obtaining cheap land through the Homestead Act.

Unfortunately, by the 1870s, most of the best lands offering

good soil and climate had been claimed, and they were forced

to settle in more arid parts of the state.

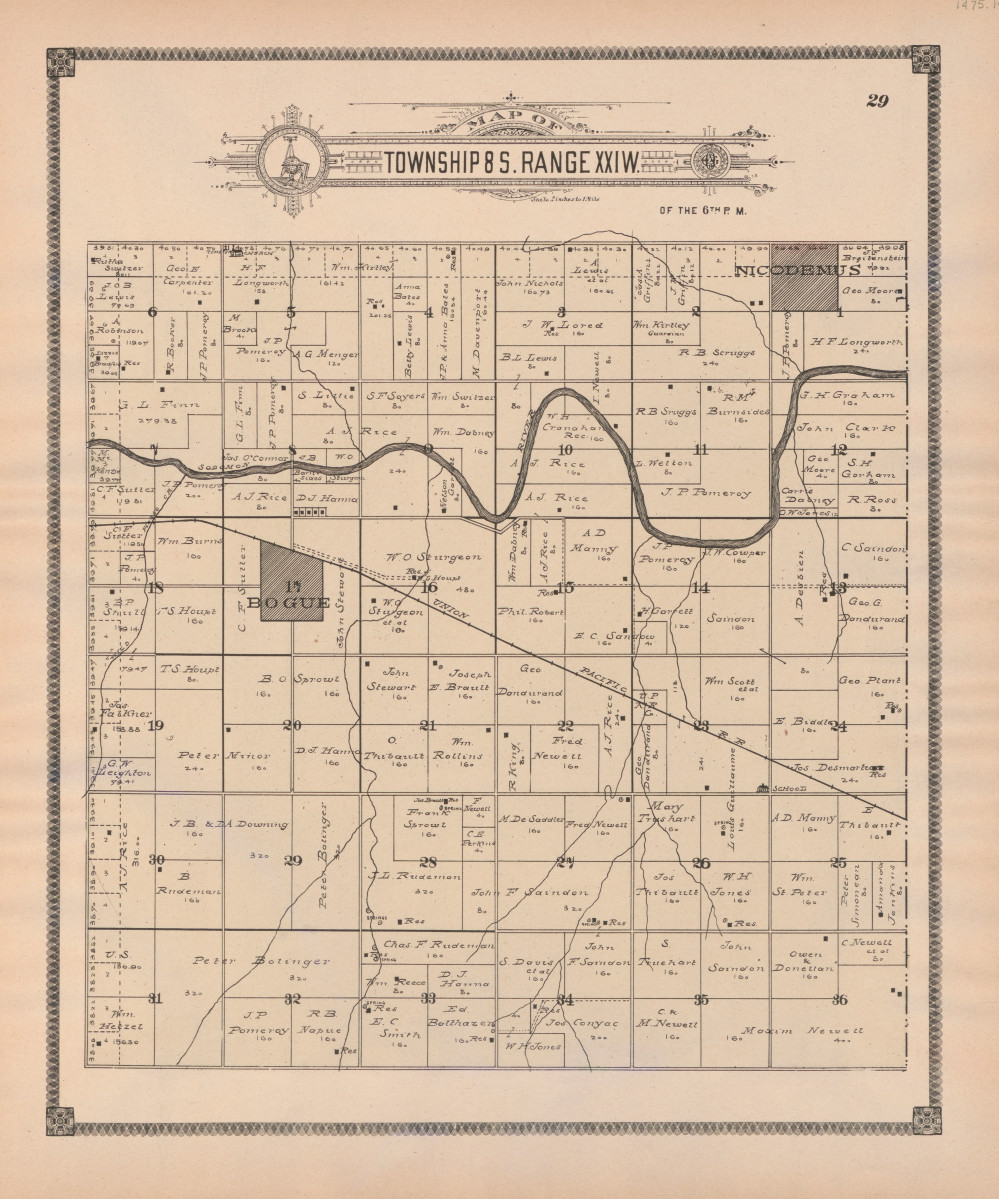

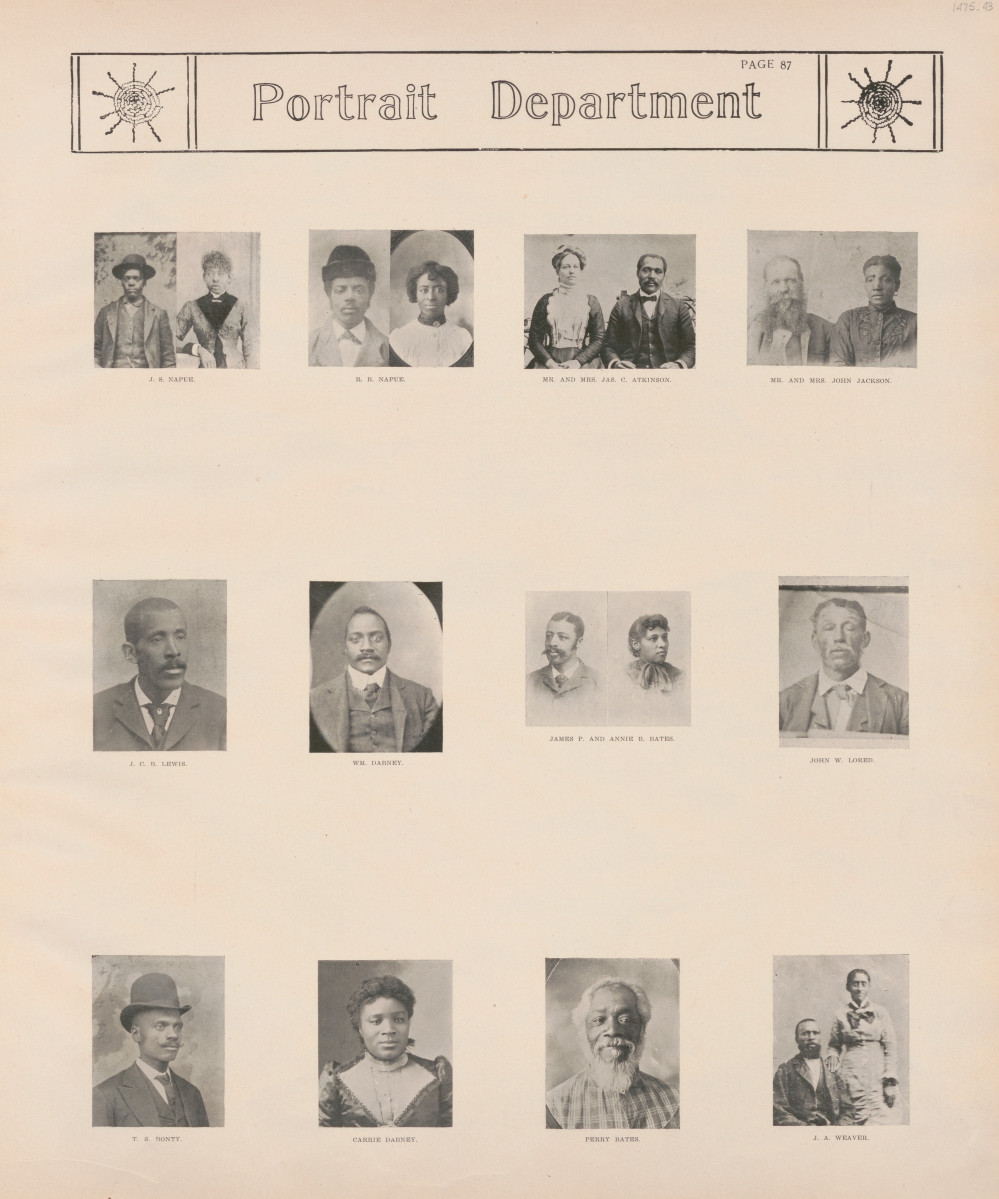

“Township 8 S. Range XXI W.” and “Portrait Department” from

George A. Ogle,

Standard Atlas of Graham County, Kansas.

Chicago, 1906. Atlas pages, 18 x 15 inches. Courtesy

of Library of Congress Geography and Map Division. Reproduction 2019.

One Black town founded during this period was Nicodemus,

located on the high plains of western Kansas, as depicted in a

county atlas. The town was founded in 1877, growing to 600 by

1880. The town’s efforts to attract the railroad failed, and

its population and prosperity were declining by the time this

atlas was published. The portrait section, a common feature of

county atlases, provides evidence of the African American

settlement, since the very last page displays portraits of 12

African American families, six of which can be located on this

township map. Others were located in surrounding townships.

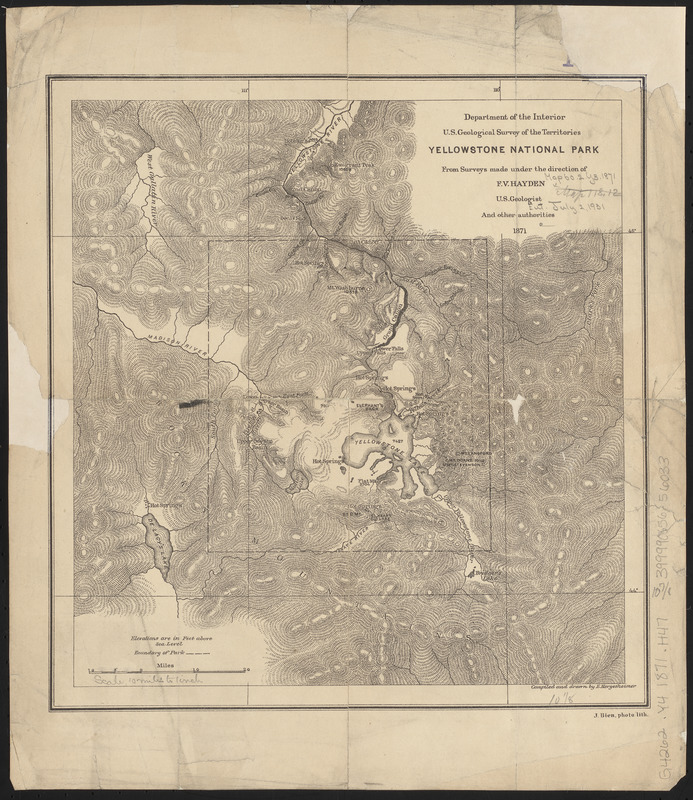

Ferdinand V. Hayden (1829-1887)

Yellowstone National Park

Washington, D.C., 1871. Printed map, 15 x 12.5

inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

During the last half of the 19th century, Americans expressed

concern about the environmental costs of clearing forests,

mining, and flourishing industries. Early conservation

advocates sought to preserve the spectacular scenery as well

as the land, water, and forests. However, the driving mission

of the national parks movement—to preserve natural landscapes

untouched by human interference—involved the systemic

oppression and removal of Native people. In 1872, Congress

designated the headwaters of the Yellowstone River in

northwestern Wyoming as the first national park. The pursuit

of a pristine wilderness necessitated the forcible removal of

the Bannock and Shoshone people from Yellowstone.

Thomas Moran (1837-1926)

The Grand Canyon, Yellowstone

Boston, 1875. Chromolithograph, 9.75 x 14 inches.

Courtesy of Boston Public Library, Print Department. Reproduction 2019.

In the mid-19th century, Americans began advocating for

landscape conservation out of fear that the West’s beauty

would be lost. In 1872, Congress designated Yellowstone as the

first national park. Louis Prang’s print of the Grand Canyon

of the Yellowstone River, based on a painting by artist Thomas

Moran, dramatizes light shining onto waterfalls carved into

mountains. Images like this reinforced the misconception that

the West was a largely uninhabited and untouched wild

environment.

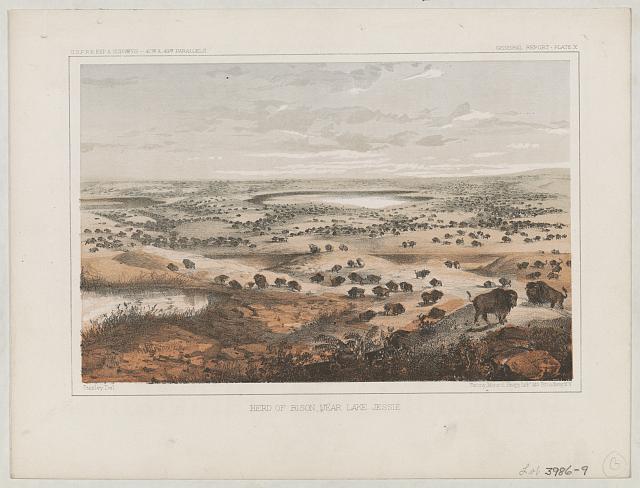

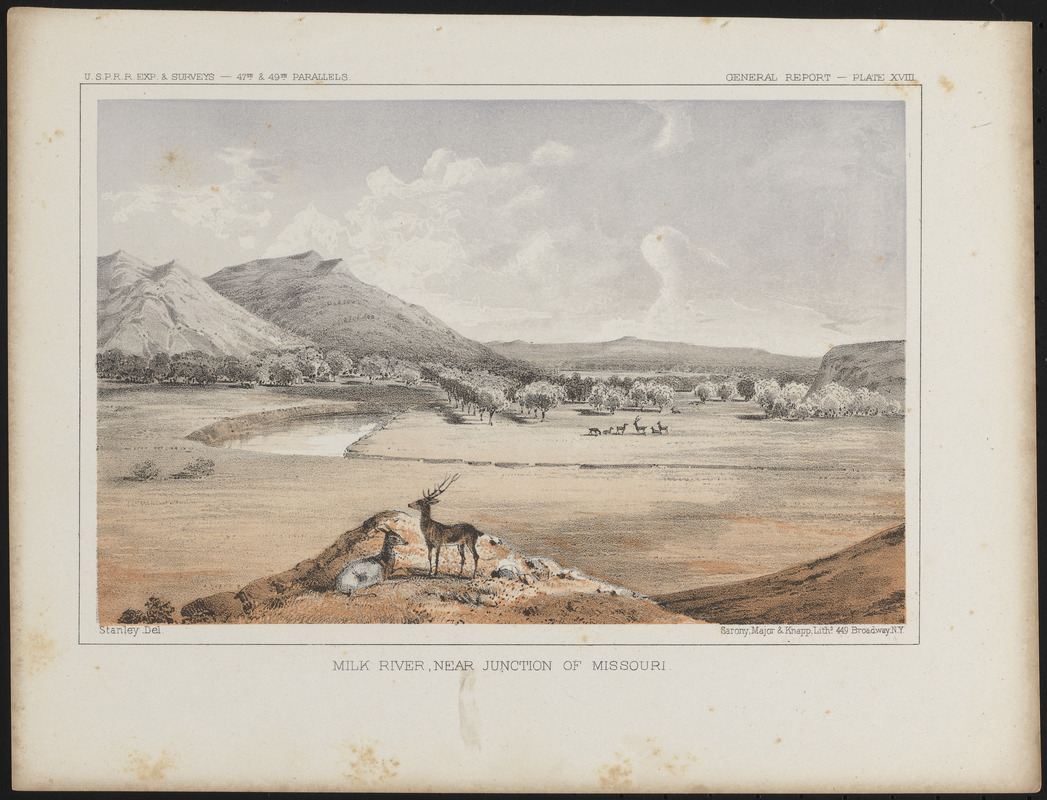

John Mix Stanley (1814-1872)

"Herd of Bison, near

Lake Jessie," from

Reports of Explorations and Surveys, to Ascertain the

Most Practicable and Economical Route for a Railroad …

Washington, D.C., 1855-1860. Lithograph print, 8.5 x

11.5 inches. Courtesy of

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Reproduction 2019.

The abundance of bison still living on the Great Plains at

mid-century is documented in this landscape view by John Mix

Stanley. It depicts a large herd dotting the North Dakota

landscape as far as the eye can see. Stanley, who served as

the lead artist for Isaac Stevens’ Northern Pacific Railroad

survey in 1853-1854, prepared a variety of views recording

scenery, Native peoples, and wildlife which were used for 55

illustrations in the final published report of the railroad

survey.

George Catlin (1796-1872)

"Buffalo Hunt, Chase," from

Catlin’s North American Indian Portfolio

New

York, 1845. Lithograph print, 16 x 22 inches. Courtesy of

New York Public Library Rare Book Division. Reproduction 2019.

In contrast, George Catlin’s illustration provides a dramatic,

romanticized, Euro-American vision of the West—armed only with

spears and bows and arrows, Native people hunt bison on

horseback. This rendition evokes excitement of the high-speed

chase and the daring of these hunters before such powerful

animals. Catlin featured the print in his

North American Indian Portfolio. He focused less on

detailing an accurate landscape, and more on manufacturing

scenes that would appeal to readers.

Clarence King (1842-1901) and James T. Gardiner (1842-1912)

Map of the Yosemite Valley …

Washington,

D.C., 1870. Printed map, 19.25 x 28 inches. Leventhal Map

and Education Center.

In 1890, California's Yosemite Valley became the second

national park, although it had already been set aside as a

state preserve in 1864, following the violent expulsion of the

Ahwahnechee people. Both Yellowstone and Yosemite were mapped

as part of four Great Western Surveys that preceded the

establishment of the U.S. Geological Survey in 1879. Clarence

King, who headed the Geological Exploration of the Fortieth

Parallel, mapped Yosemite in 1870, while F. V. Hayden, who led

the Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories,

mapped Yellowstone in 1871. Both used the traditional method

of hachuring—drawing ink strokes along sloped land—to depict

the rugged terrain of these unusual landscapes.

2a. ECONOMY 1800-1862: Transforming the Landscape through Agriculture, Mining, and Industry

While many Euro-Americans believed they were settlers in an untouched wilderness, Native people had altered the landscape by managing forests, growing crops, hunting, igniting seasonal burnings, and building communities for millennia. As U.S. government officials explored, mapped and inventoried the lands west of the Appalachians, they advertised the fertility of the soil and the presence of mineral resources. American settlers cleared the forests to create farms and scarred the earth to mine for resources, which eventually drove the construction of industrial towns and cities.

Timber and coal fueled new factories in urban centers that processed agricultural and mineral products into marketable items. Under colonial and U.S. rule of law, this change was known legally as “improving” the land. Wealth generated from resource extraction and the labor of enslaved and free workers enriched the prospects of a small but very rich upper class, though new industrial jobs and small subsistence farms did lift some free laborers and farmers out of poverty.

VIEWPOINT: When looking at these maps, it's important to keep in mind that the idea of 'improving' land is an English colonial concept. Native people worked the land prior to American settlement. Disease-ravaged native populations and vast farmlands quickly returned to forest. The existing forests were managed systematically by Native peoples in different ways and for different reasons. The law said "improve", but what it meant literally was doing something to make a profit. This was usually done through farming, cutting down trees, planting crops, raising cows, chickens and pigs, and never moving. The concept that this behavior is an "improvement" is purely a European perspective.

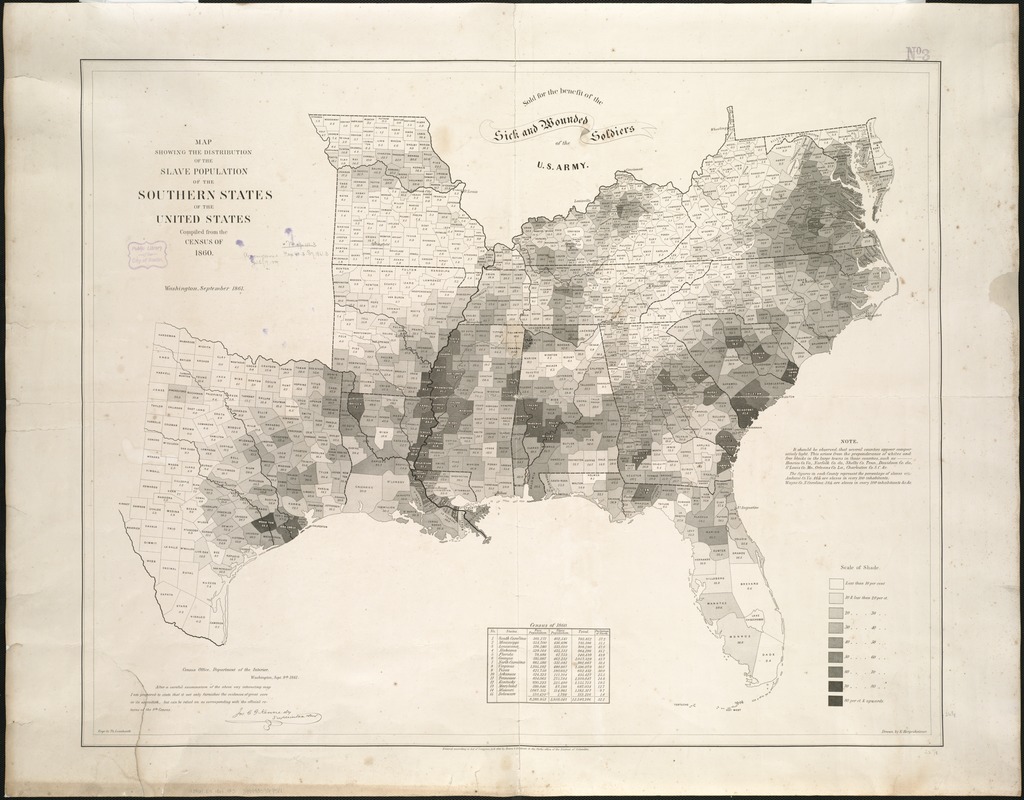

Frederick Law Olmsted (1822–1903)

“A Map of the Cotton

Kingdom and its Dependencies in America,” in “The Cotton

Kingdom”

New York, 1861. Printed map, 11 x 17 inches.

Courtesy of

Boston Public Library, Rare Books Department. Reproduction, 2019.

This statistical map addresses the importance of cotton

agriculture in the economy before the American Civil War. It

represents agricultural productivity rather than distribution

and density of cotton cultivation by mapping two variables:

productivity of cotton per enslaved laborer (blue, yellow, or

red) and ratio of enslaved people to freemen (solid versus

dashed horizontal lines). The map accompanied landscape

architect Frederick Law Olmsted’s published account of his

travels through the South during the 1850s. Hired by the “New

York Times” as a journalist to report his observations about

the region’s economy, he argued that chattel slavery was

inefficient for cotton production.

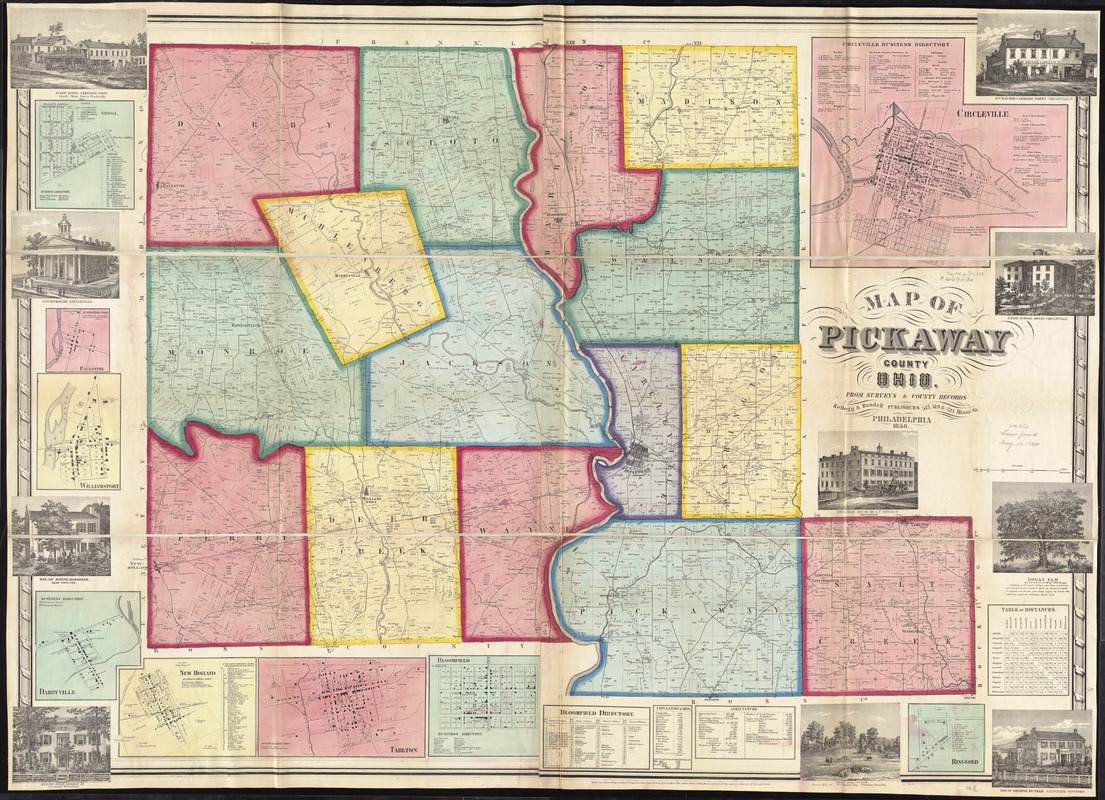

Robert Pearsall Smith (1827–1898)

“Map of Pickaway

County, Ohio, from Surveys and County Records”

Philadelphia,

1858. Printed map, 38 x 53 inches. Leventhal Map and

Education Center.

Pickaway County, located in central Ohio about 25 miles south

of Columbus, provides a good example of a rural Midwestern

county where the economy was based on diversified agriculture

during the first half of 19th century. The statistical tables

along the bottom margin of this land ownership map indicate

that the county had a population of 21,000 and farms were

valued at $6 million. Agricultural production included a

variety of livestock (horses, cows, oxen, sheep, and swine)

and crops (corn, wheat, rye, oats, hay, and potatoes). The map

also displays the boundaries of individual landholdings,

indicating that most were small farms containing several

hundred acres.

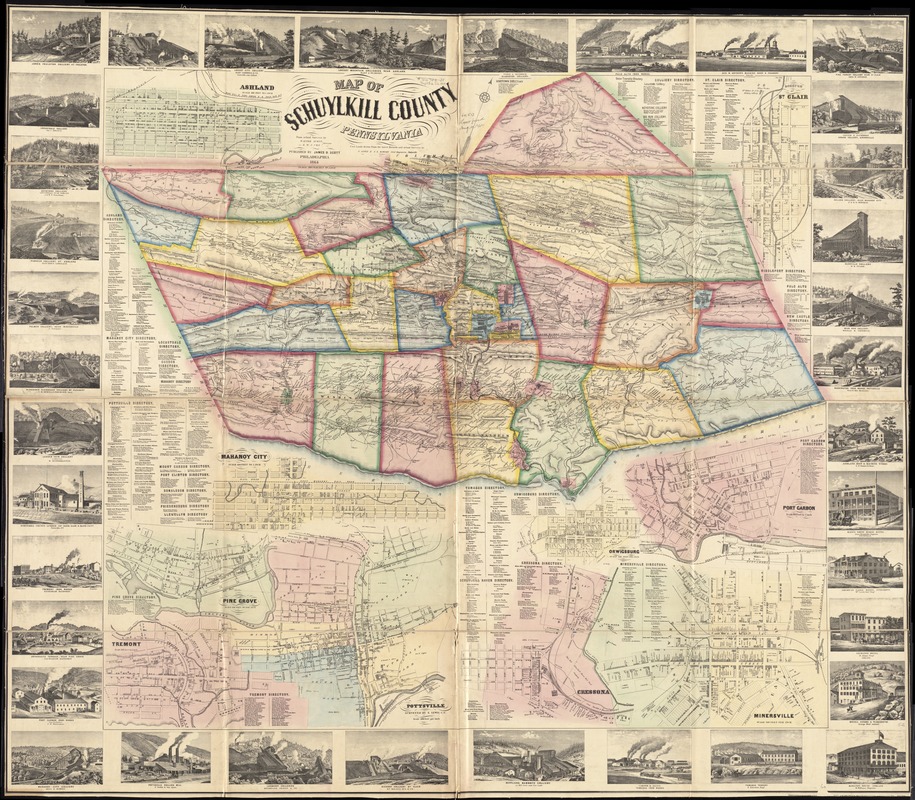

James D. Scott (fl. 1854–1889)

“Map of Schuylkill

County, Pennsylvania”

Philadelphia, 1864. Printed map,

45 x 50 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

The economy of Schuylkill County, located in northeastern

Pennsylvania, focused on anthracite coal mining during the

19th century. This county map documents how that activity

dominated the landscape. Of the 37 marginal vignettes, 20

illustrate collieries – coal mines and connected buildings. An

additional ten depict local iron manufacturers, fueled by the

region’s coal. Also evident is the network of railroads and

canals that shipped these resources to New York City and

Philadelphia. The map identifies landowners’ names including

many coal companies, and also displays street plans and

directories for 23 towns, detailing retail activities and

service industries within each.

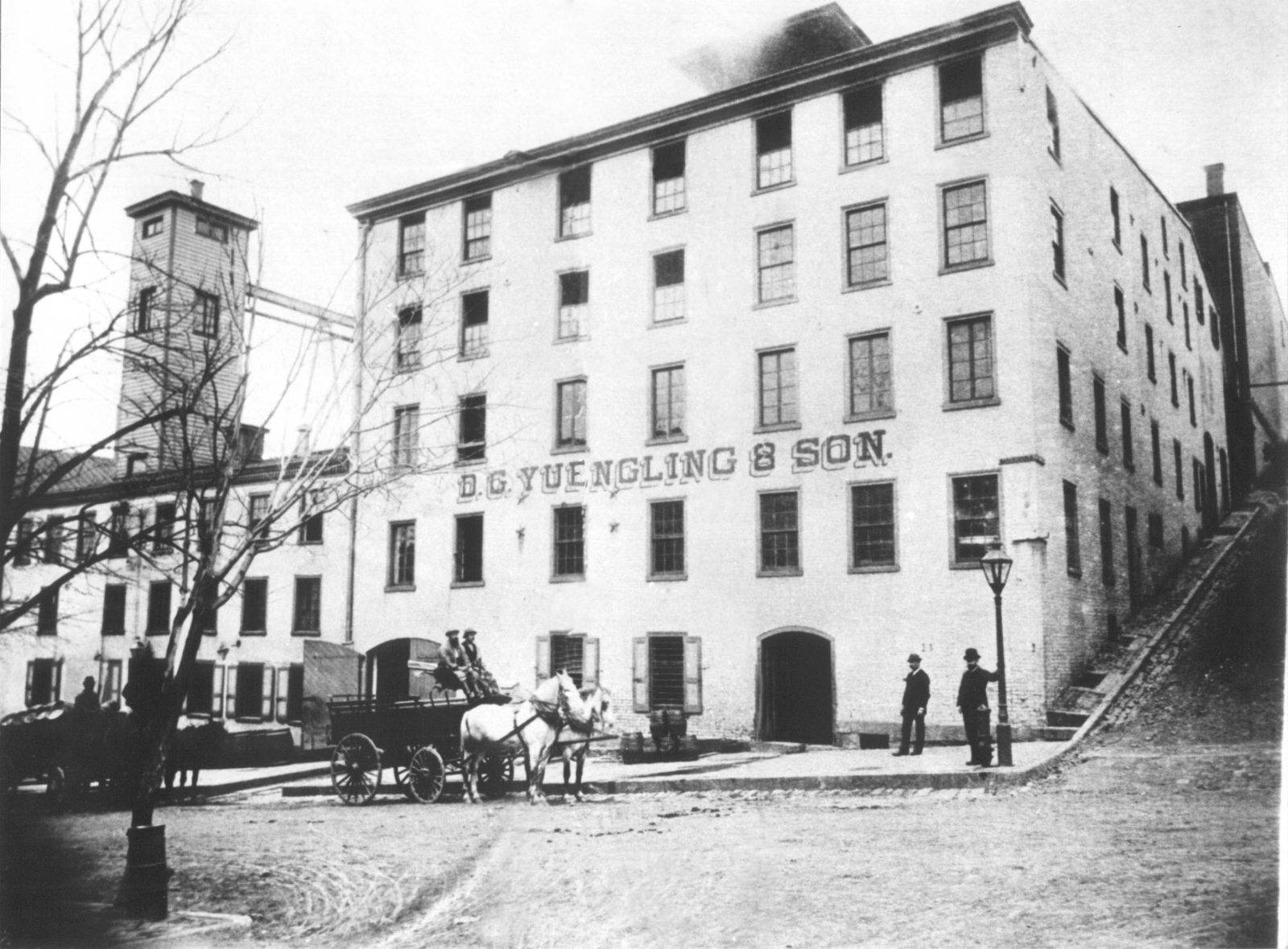

“Exterior View of D.G. Yuengling & Son Brewery”

Ca.

1855. Photographic print, 8 x 11 inches.

Courtesy of D.G. Yuengling & Son, Inc.

Reproduction, 2019.

The street map for Pottsville, the county seat and largest

town, accompanies a directory with 110 listings. Yuengling

brewery, which is the oldest brewery in the United States

still in operation today, appears in the list and is located

on the town map. This photograph, taken around 1855, is the

earliest known image of the brewery. David G. Jüngling, who

immigrated from Germany, founded the brewery in 1829. He

changed the spelling of his name to Yuengling so that

Americans could pronounce it. He anticipated that

locals—especially the many German immigrants who lived in the

region—would purchase his product.

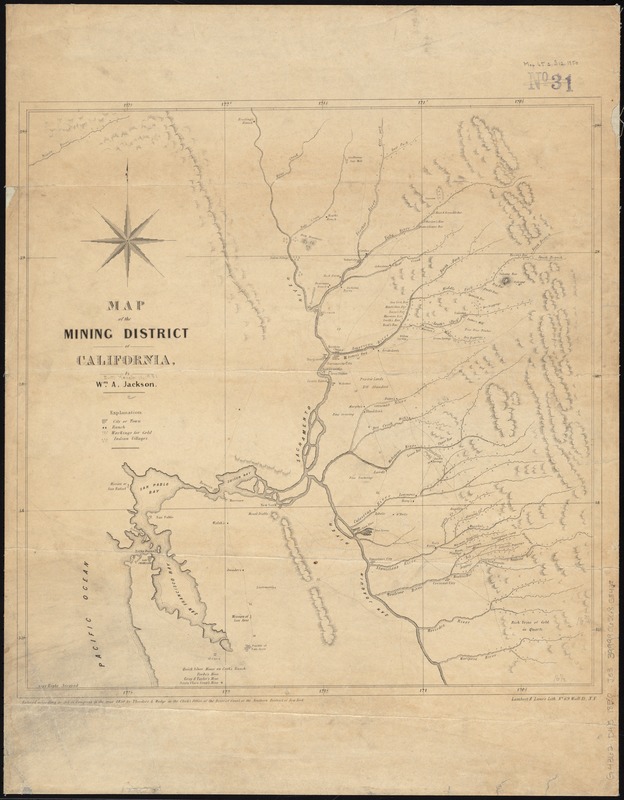

William A. Jackson (fl. 1850)

“Map of the Mining

District of California”

New York, 1850. Printed map, 17

x 17 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

Immediately prior to the discovery of gold in 1848, central

California was home to Native communities; Mexican missions,

ranchos, and pueblos; the small

presidio—fortified military settlement—of San

Francisco; and a few white American residents. Published two

years later, this map testifies to the frantic pace of

settlement during the California Gold Rush. By 1855, over

300,000 immigrants from the eastern United States, Europe,

Latin America, Australia, and China established mining camps,

towns, and roads. San Francisco grew rapidly. By the 1870s,

California’s Native population plummeted from an estimated

150,000 to 30,000. Thousands were forcibly removed from their

homelands, enslaved, or killed. Early legislation in

California made it lucrative to enslave Native peoples, or to

be paid for exterminating them.

U.S. General Land Office

“Map of the Public Land

States and Territories …”

Washington, DC, 1864. Printed

map, 30 x 44 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

This map, one of the first thematic maps of the United States

published by the General Land Office, provided an inventory of

the nation’s land and mineral resources. Besides showing the

extent of township surveys, it locates local land offices and

completed, uncompleted, and projected railroads. In addition,

it uses color coding to identify the locations of six mineral

resources – gold (yellow), silver (red), copper (green),

quicksilver (blue), tin (purple) and coal (gray) – primarily

covering extensive areas of the western states and

territories. Ignoring the presence of Native peoples in this

region, the map suggests that the minerals are readily

available for exploitation.

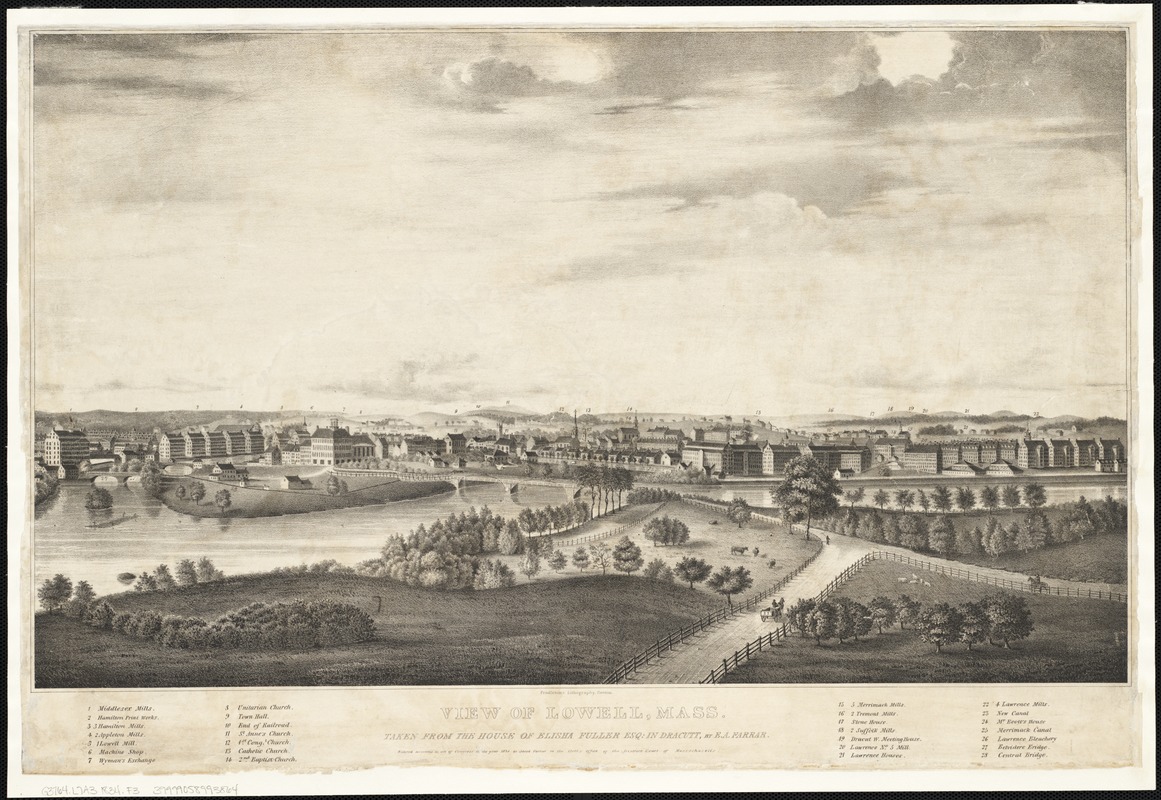

E.A. Farrar (fl. 1834)

“View of Lowell, Mass. …”

Boston,

1834. Printed view, 14.25 x 24 inches. Leventhal Map and

Education Center.

Lowell, Massachusetts, the first planned company mill town, is

recognized as the cradle of America’s Industrial Revolution.

In the 1820s, Boston financiers founded the town when they

constructed a textile factory on a canal bypassing the

Merrimack River’s Pawtucket Falls. By mid-century, Lowell was

the largest industrial complex in the United States. The

textile economy relied on cotton grown by enslaved people in

the South. The jobs attracted young women from rural New

England, and immigrants from French Canada, Germany, and

Ireland. The accompanying view, published in 1834, illustrates

how the mills dominated the city’s landscape when viewed from

the north side of the Merrimack River.

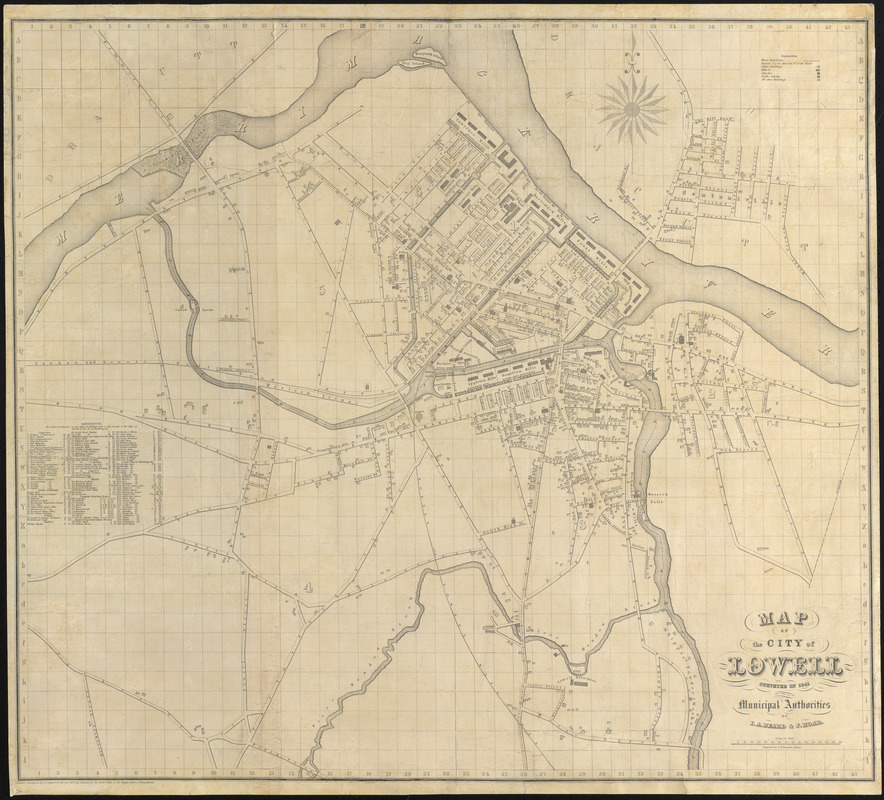

Ithamar A. Beard and J. Hoar

“Map of the City of

Lowell Surveyed in 1841 …”

Boston, 1842. Printed map, 30.5 x 34 inches. Courtesy of

Lawrence Caldwell.

By the early 1840s, when this map was prepared, Lowell had

grown to a population of more than 20,000, making it the

state’s second largest city. The map details the footprint and

function of individual buildings and demonstrates how dominant

the textile industry was in the community. The map notes ten

named textile mills as well as an additional 19 mills and

factories. Mills were located near the river and canals, which

provided waterpower for the factories. The directory lists

company boarding houses, agents and superintendent houses, as

well as numerous churches, schools, and other public

buildings.

Winslow Homer (1836–1910)

“The Bobbin Girl,” from

William Cullen Bryant, “Song of the Sower”

New York,

1871. Print. Courtesy of the

American Antiquarian Society. Reproduction, 2019.

The role of women in the textile industry is reflected in this

illustration by Winslow Homer. The same year that the

accompanying view was published, the textile workers formed

the nation’s first union of working women, “turning out”

(striking) in response to proposed wage cuts and blazing a

trail for union workers.

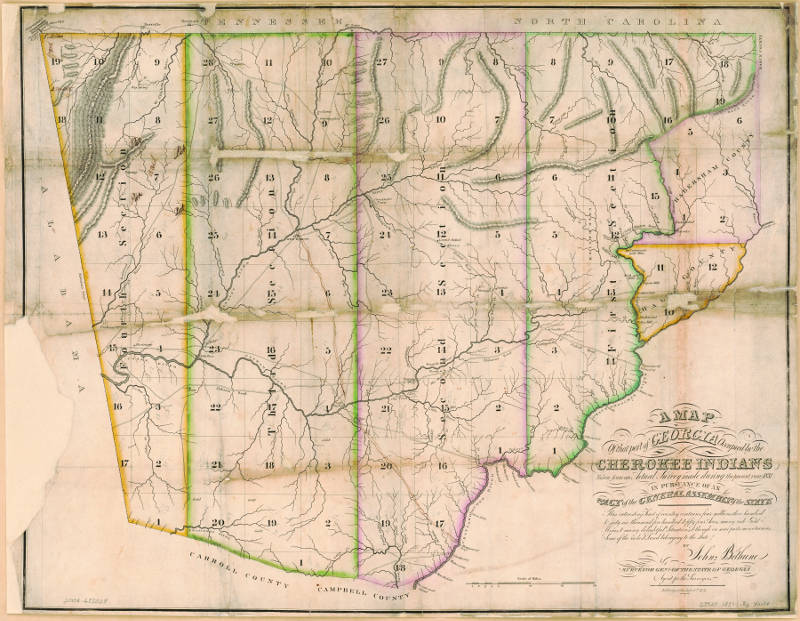

John Bethune (1770–1861)

“A Map of That Part of

Georgia Occupied by the Cherokee Indians … “

Milledgeville,

GA, 1831. Printed map, 20.5 x 26.5 inches. Courtesy of the

Library of Congress Geography and Map Division. Reproduction, 2019.

The cultural and economic landscape of northwestern Georgia

underwent dramatic changes before the American Civil War. This

region formed part of the Tsalagi (Cherokee) homelands until

the U.S. government forced the tribe’s removal to the Great

Plains from 1836 to 1839. Gold was discovered in 1828,

initiating one of the nation's first gold rushes and hastening

their expulsion. This map, prepared in 1831 by the Georgia

Surveyor General, promoted the richness of the area,

especially the gold mines and fertile soil coveted by

settlers. Besides locating a number of gold mines, the map

also displayed Tsalagi communities and roads.

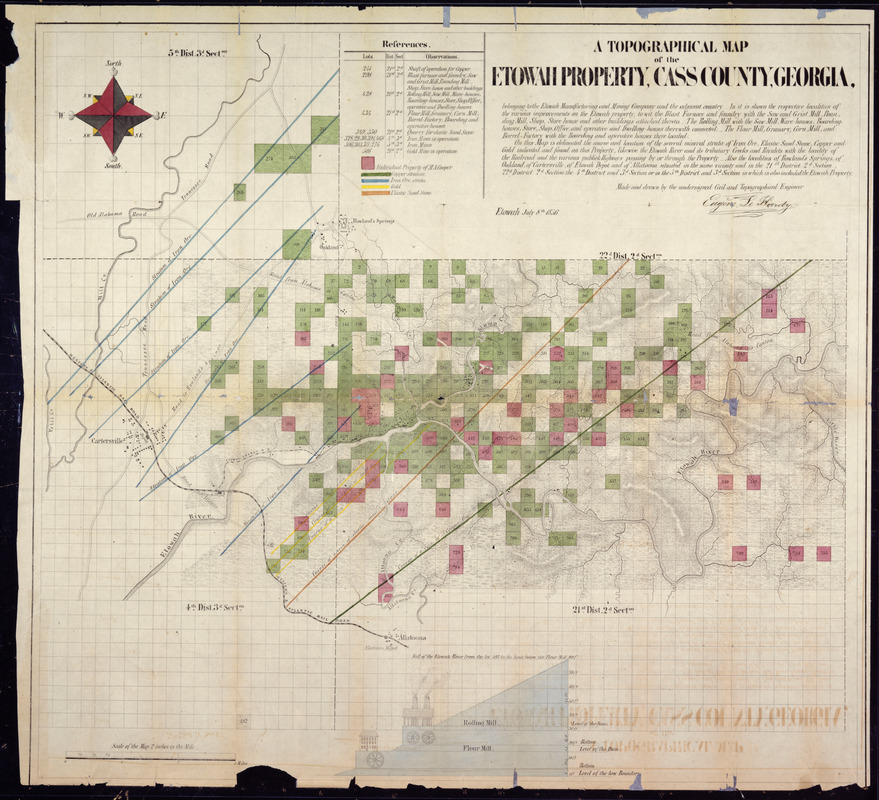

Eugene LeHardy (fl. 1856)

“A Topographic Map of the

Etowah Property, Cass County, Georgia”

Etowah, GA,

1856. Film of printed map, 5.5 x 8 inches. Courtesy of

National Archives and Records Administration. Reproduction, 2019.

Georgia’s gold rush ended by the early 1840s, but the discovery of other mineral resources, including iron, furthered the extensive exploitation of the landscape. During the first half of the 19th century, iron furnaces, which relied on charcoal, tended to be small rural operations located near iron deposits. One example is the Etowah Manufacturing and Mining Company located in northwestern Georgia. The accompanying topographic map shows that the small village encompassed the furnace, rolling mill, and workers’ housing and stores, while the company owned at least 10,000 acres of surrounding forest. This landscape was altered by cutting down massive amounts of timber to produce charcoal.

2b. ECONOMY 1862-1900: Transforming the Landscape through Agriculture, Mining and Industry

While many Euro-Americans believed they were settlers in an untouched wilderness, Native people had altered the landscape by managing forests, growing crops, hunting, igniting seasonal burnings, and building communities for millennia. Different Native peoples developed relations with Spanish, French, Dutch, and English colonial powers. In trading partnerships, especially with the French and British, they often hunted animals and finished pelts that reached Europe and Asia as part of a global fur trade.

As U.S. government officials mapped and inventoried the lands west of the Appalachians, they advertised the fertility of the soil and the presence of mineral resources to American settlers who in turn pursued a more intensive exploitation of the landscape. They cleared the forests to create farms and scarred the earth to mine for resources, which eventually drove the construction of modern cities. Timber and coal fueled new factories in urban centers that processed agricultural and mineral products into marketable items. Under colonial and U.S. legal systems, this change was known legally as “improving” the land.

For Kids

Ranchers, farmers, miners, tradespeople,

and bankers all contributed to the wealth of the expanding

United States and the growth of cities. Another group’s

relationship to the economy changed drastically after the

Civil War: formerly enslaved people and their descendants.

Though not free from racism and discrimination, their embrace

of new opportunities changed the country in meaningful ways.

- These maps show how farms, mines, factories and new cities spread across the country. What is not shown?

- What stories do the maps tell about the relationships between people, the environment and money?

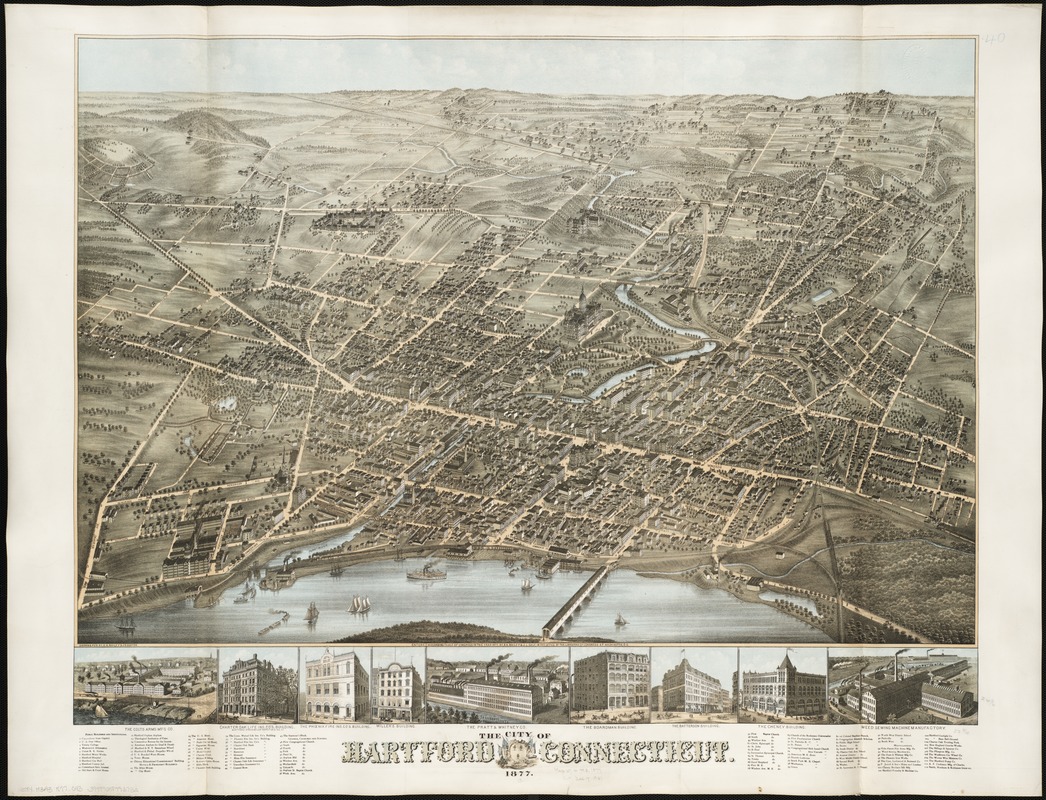

Oakley Hoopes Bailey (1843-1947)

The City of Hartford, Connecticut

Boston, 1877. Printed map, 25 x 33 inches. Leventhal

Map and Education Center.

For several decades following the Civil War, Hartford,

Connecticut ranked as the richest city in the nation. As the

headquarters for numerous insurance companies, it was known as

the “insurance capital of the world.” The city also led the

Industrial Revolution as a large producer of guns, sewing

machines, and machine tools. One marginal inset illustrates

the Colt Arms Manufacturing Company, which produced guns

widely used during the Civil War and in later conflicts with

western tribal nations. This panoramic view from the east

captures the city’s economic diversity in the 1870s, when it

had reached a population of 40,000.

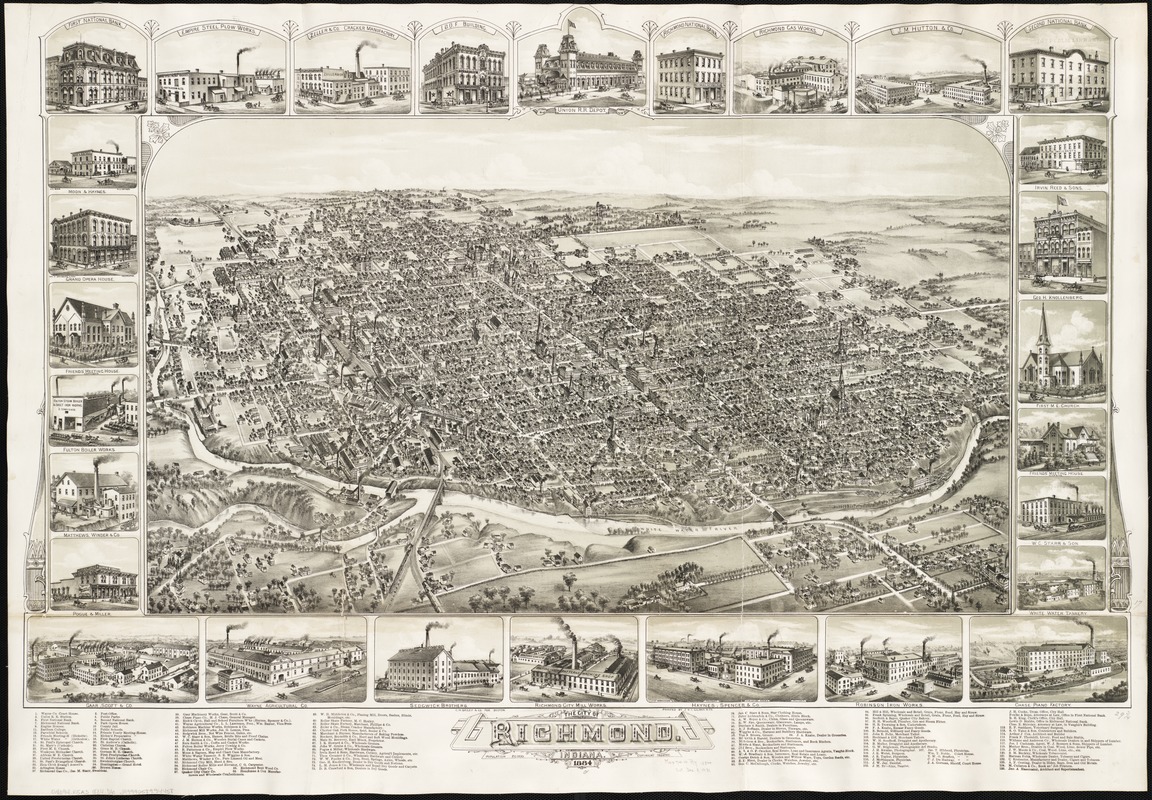

Albert E. Downs (fl. 1880-1916)

The City of Richmond, Indiana

Boston, 1884. Printed map, 24.5 x 37 inches.

Leventhal Map and Education Center.

Richmond, Indiana, located on the original National Road near

the Indiana-Ohio boundary, provides an example of a midwestern

industrial town that was a center of government, commerce,

finance, and education. Oriented with east at the top, this

bird’s-eye view places the White Water River and the railroad

crossing in the foreground. The map’s directory lists 29

industrial enterprises. Many local factories manufactured farm

implements and processed agricultural produce. The largest

companies produced threshing machines, grain drillers, and

mowers, while smaller plants made crackers, baking powder, and

linseed oil. Others built non-agricultural goods, such as

pianos, caskets, boilers, and even map cases.

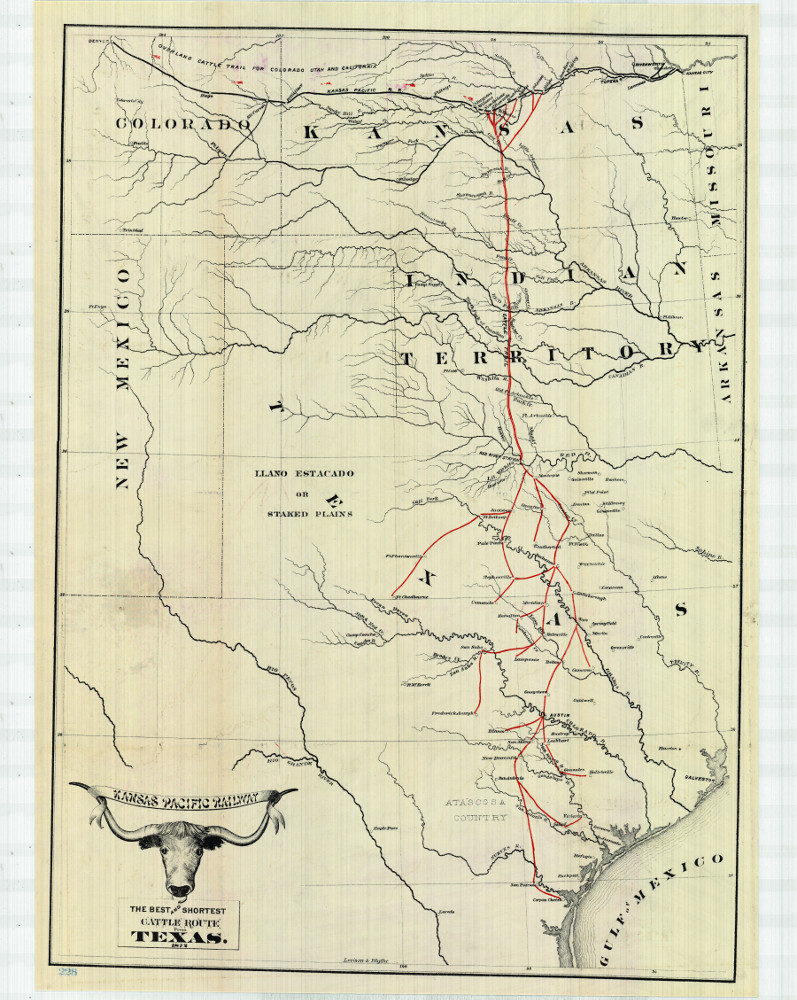

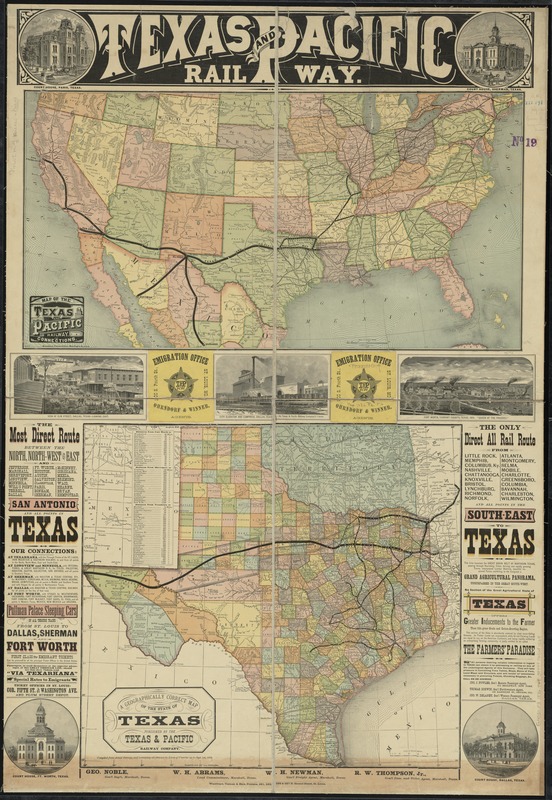

Kansas Pacific Railway

The Best and Shortest Cattle Route from Texas

St. Louis, 1872. Printed map, 20 x 14.5 inches.

Courtesy of Library of Congress Geography and Map Division. Reproduction 2019.

Modern fiction, movies, and television depict cattle drives as

an iconic image of the American West. In reality, they only

occurred from 1868 to 1886. Cowboys drove herds of 2,000 to

3,000 longhorn cattle from Texas ranches north through Indian

Territory to Kansas, as illustrated on this map. From Kansas

railheads, cattle were shipped east to stockyards and

slaughterhouses or west to mining towns and military posts.

The route provided sufficient grass, avoided tolls charged by

tribal nations, and veered around farms in eastern Kansas, but

the routes kept shifting westward to avoid expanding white

settlements. The success of the cattle industry hinged upon

the removal of Native people and wildlife.

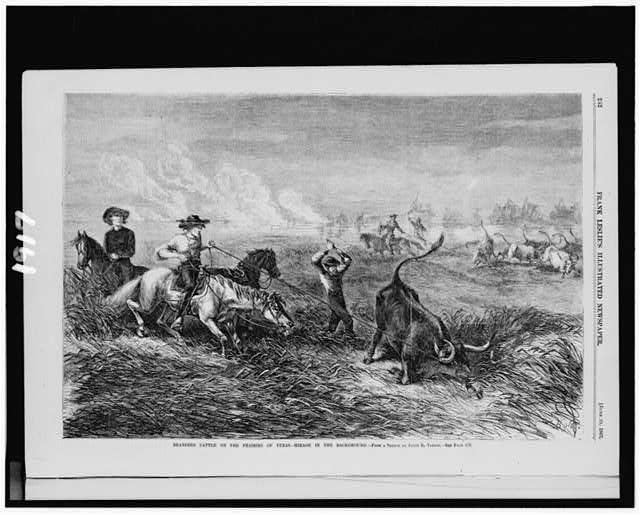

James E. Taylor (1839-1901)

“Branding Cattle on the

Prairies of Texas …” from

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper

June 29,

1867. Wood engraving, 11 x 16 inches. Courtesy of

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Reproduction 2019.

During the late 19th century, engraved illustrations—like the

one seen here—became the first kinds of pictures that could be

produced cheaply and quickly. In this engraving, a man riding

a horse lassos a furious bull. Another man stands ready with a

brand to mark ownership, while cowboys guide groups of cattle

in the background. The engraving, and many others like it,

exalted the West as a place of excitement, where courageous

men could prove themselves by conquering animals and

nature.

Erwin E. Smith (1886-1947)

“African-American Cowboys

with their Mounts Saddled Up.” 1911/1915, Photograph, 5 x 4

inches. Courtesy of

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas. Reproduction 2019.

The cowboys of popular culture have commonly been portrayed as

white Anglo men working on cattle drives in the West.

Historians estimate, however, that as many as one in three

cowboys were either Mexican or African American in the later

half of the 19th century. Many enslaved African Americans in

Texas were skilled in tending cattle from their work on

ranches. After the Civil War, these formerly enslaved men went

on to work as cowboys, one of the few jobs available to them.

While they faced discrimination from society at large, many

period sources suggest they experienced a degree of relative

equality within their cowboy crews.

J. Hale Powers & Co.

Gift for the Grangers

Cincinnati, 1873. Chromolithograph, 21.5 x 17 inches.

Courtesy of

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Reproduction 2019.

A colorful poster portrays prosperous farmers to promote the

National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry. Founded

in 1867, the Grange, advocated for farmers’ political

interests, especially against powerful railroad companies and

provided an opportunity for farmers—men and women alike—to

socialize and learn about agricultural innovations. The

central illustration depicts a farmer, shovel in hand, in

front of his farm. Smaller images feature a Granger meeting, a

harvest dance, and men and women working on their farm.

According to this print, the Grangers helped farmers overcome

“ignorance” and “sloth” (as represented in the image in the

bottom middle) and improve their lives.

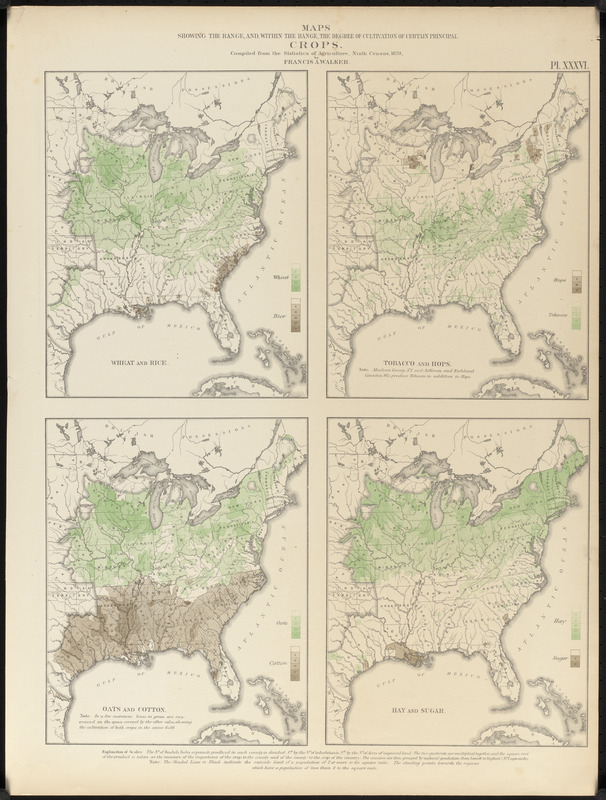

Francis A. Walker (1840-1897)

“Maps Showing the Range

… of Certain Principal Crops,” from

Statistical Atlas of the United States …

Washington, D.C., 1874. Printed map, 22 x 16.5 inches.

Leventhal Map and Education Center.

Agricultural production in the eastern United States is

represented by this plate from the statistical atlas

illustrating the 1870 census. There are four maps, each

showing the distribution and degree of cultivation of two

major crops. As the first national atlas, this prize-winning

volume was a landmark publication displaying an unprecedented

number of visual statistics and thematic maps. It was compiled

by Francis Amasa Walker, Superintendent of the ninth and tenth

censuses (taken in 1870 and 1880) and Commissioner of Indian

Affairs (1871-1872). Walker transformed the census, acquiring

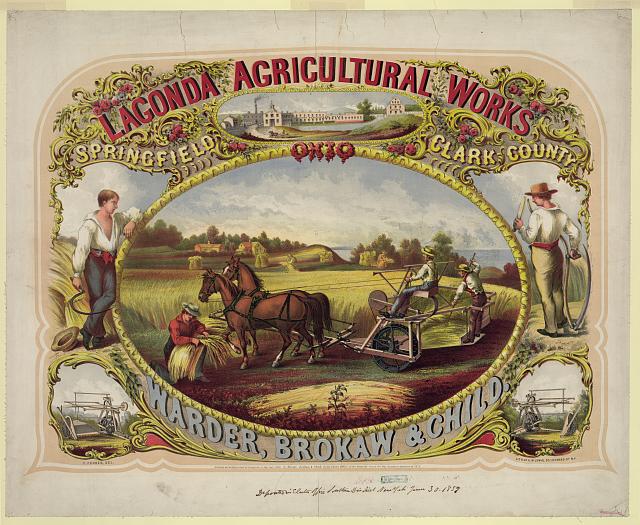

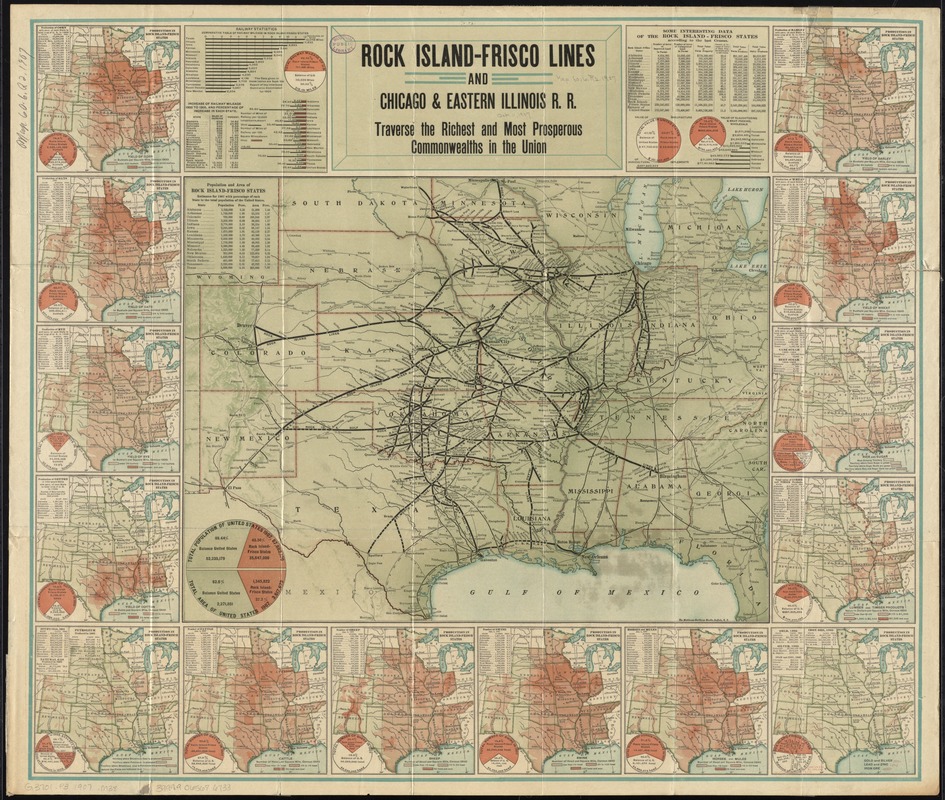

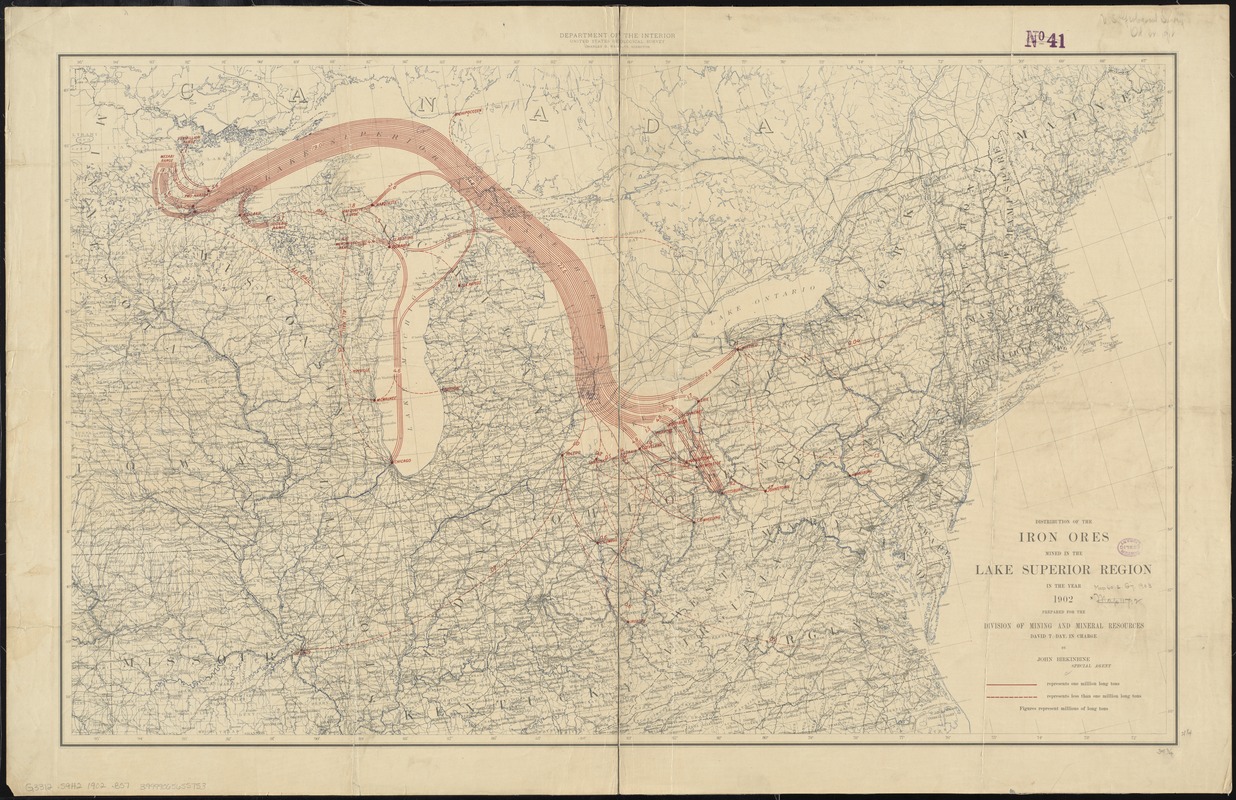

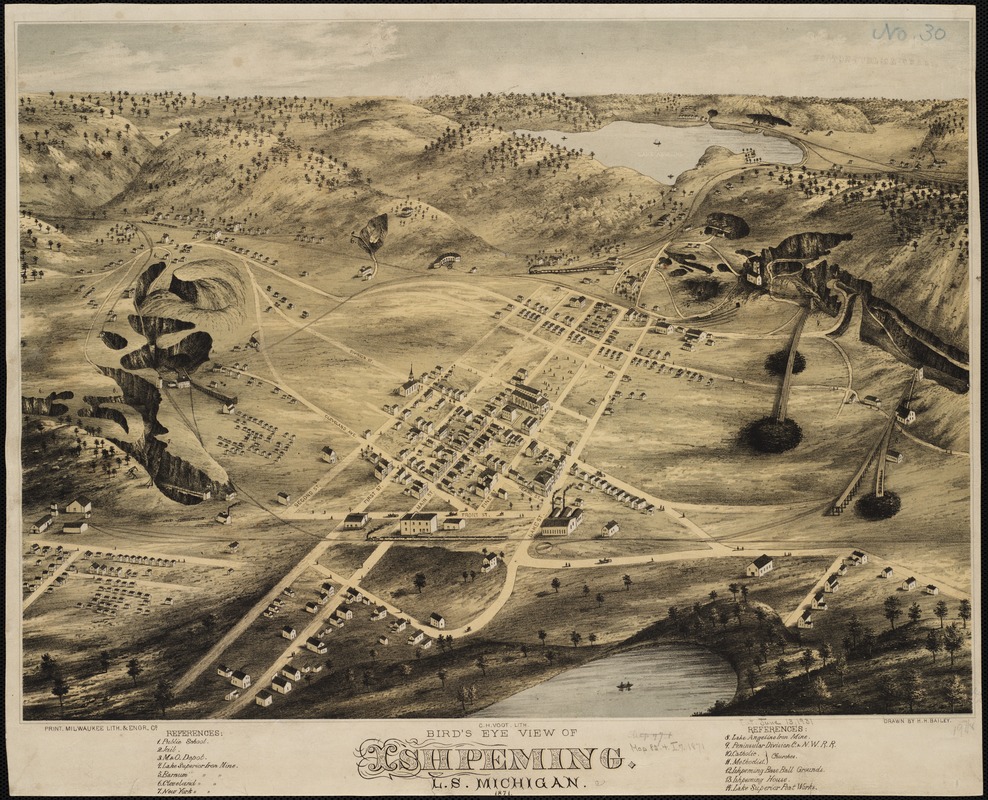

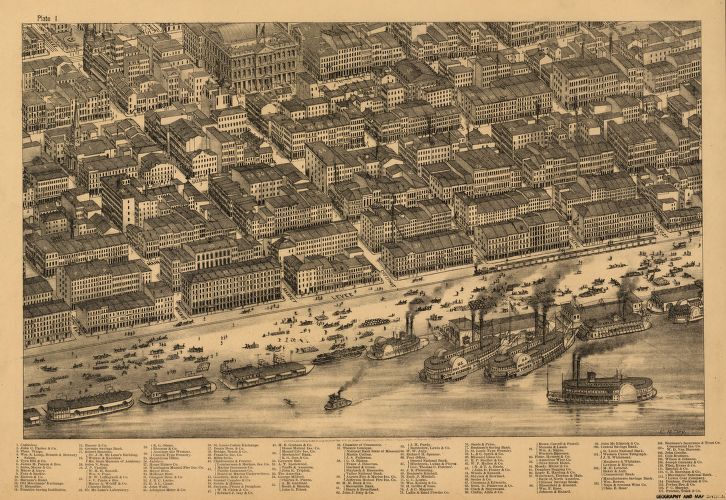

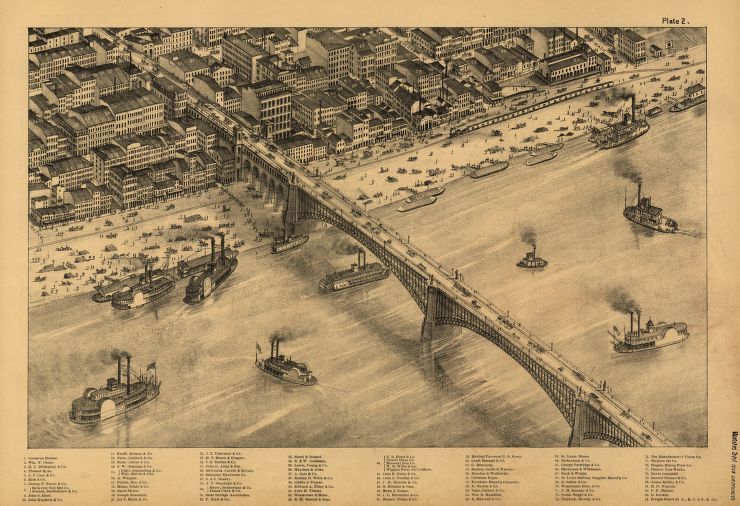

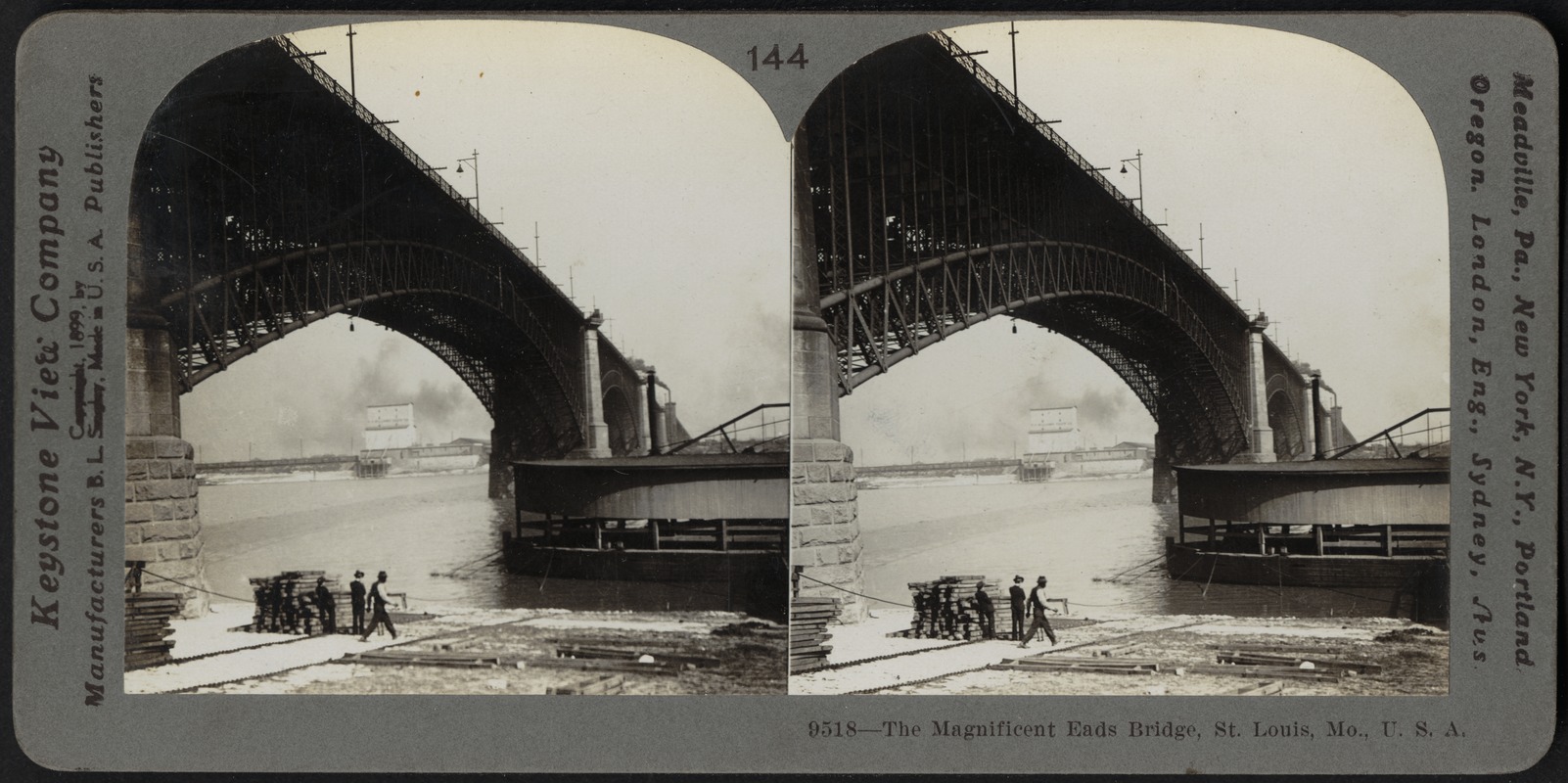

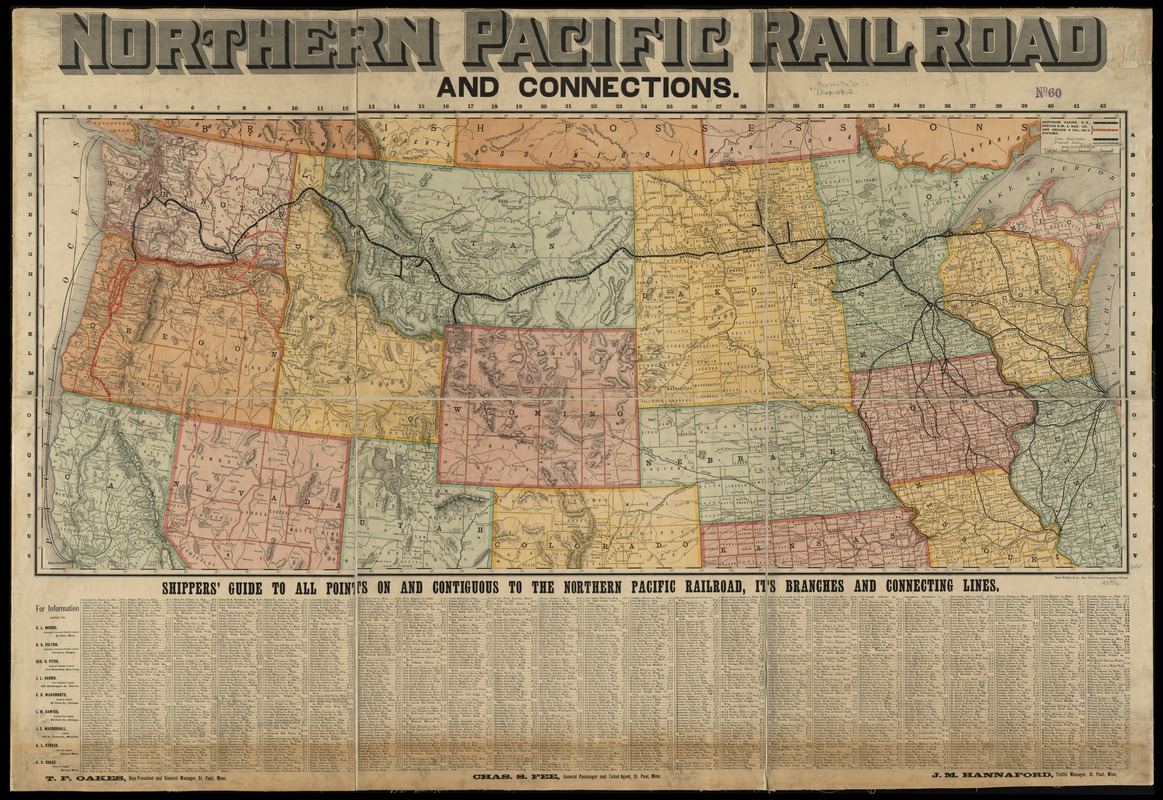

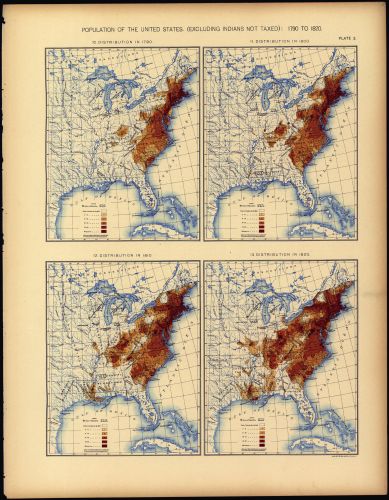

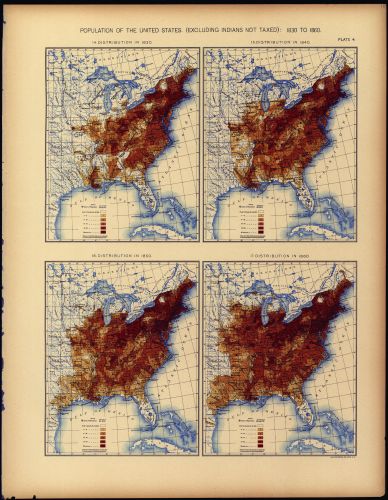

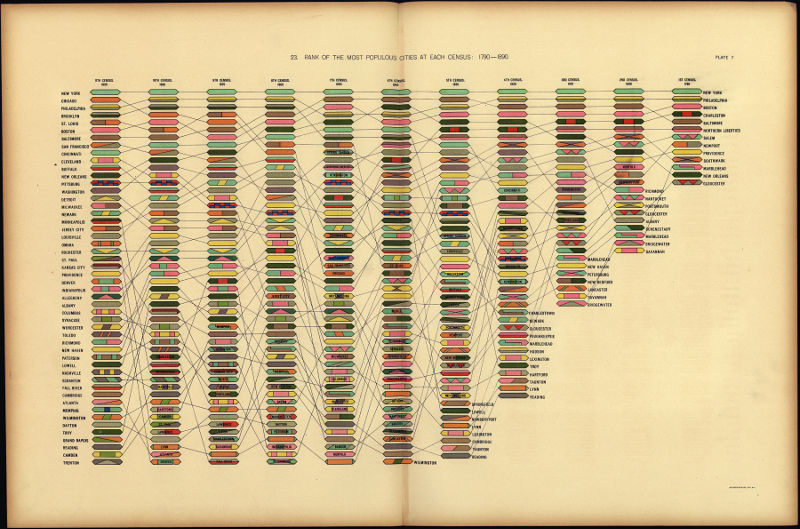

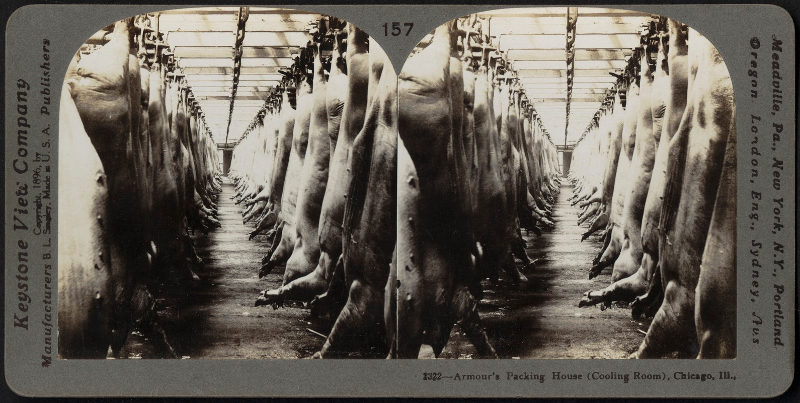

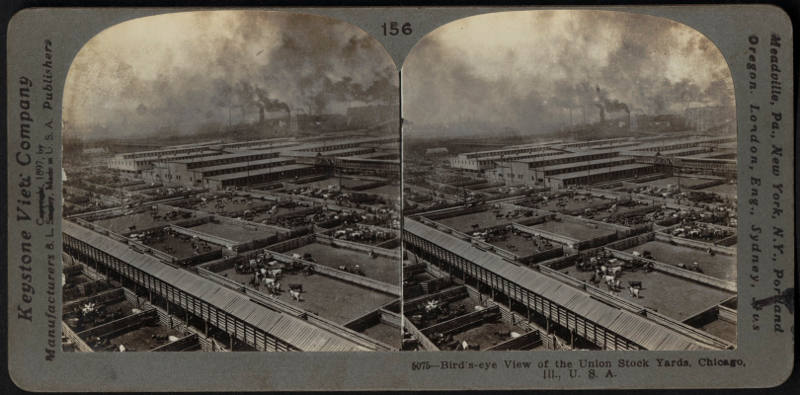

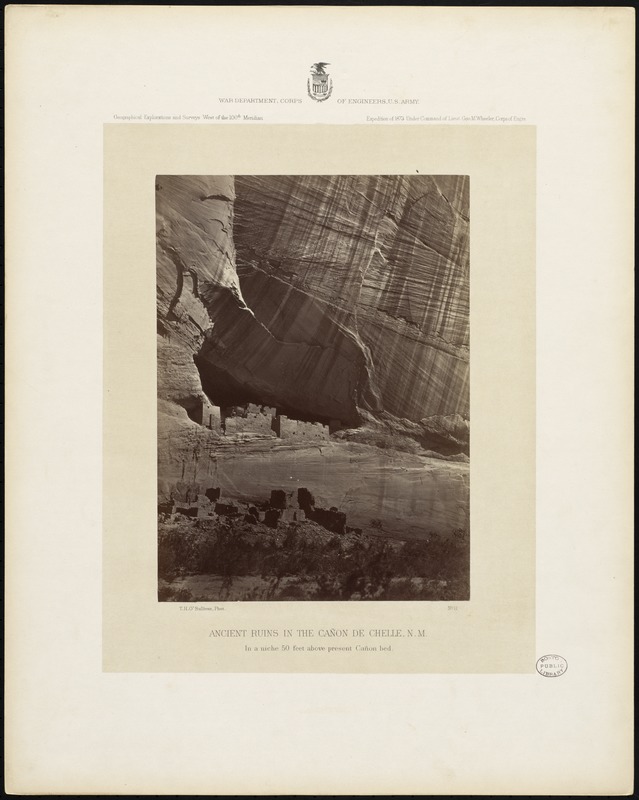

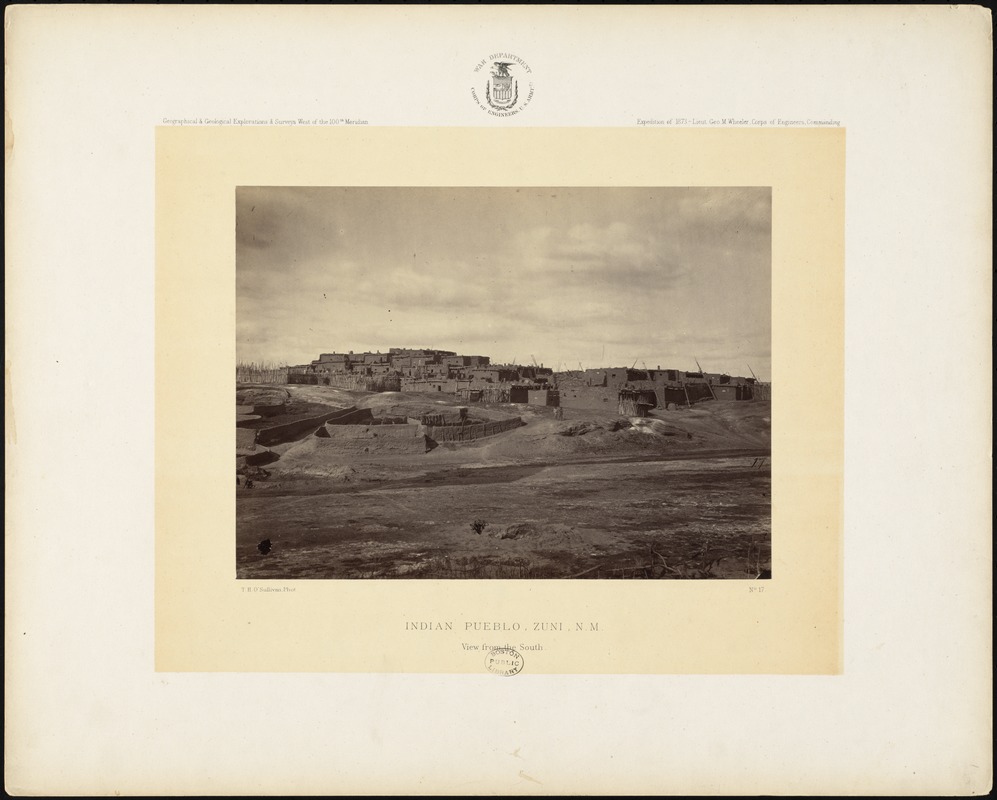

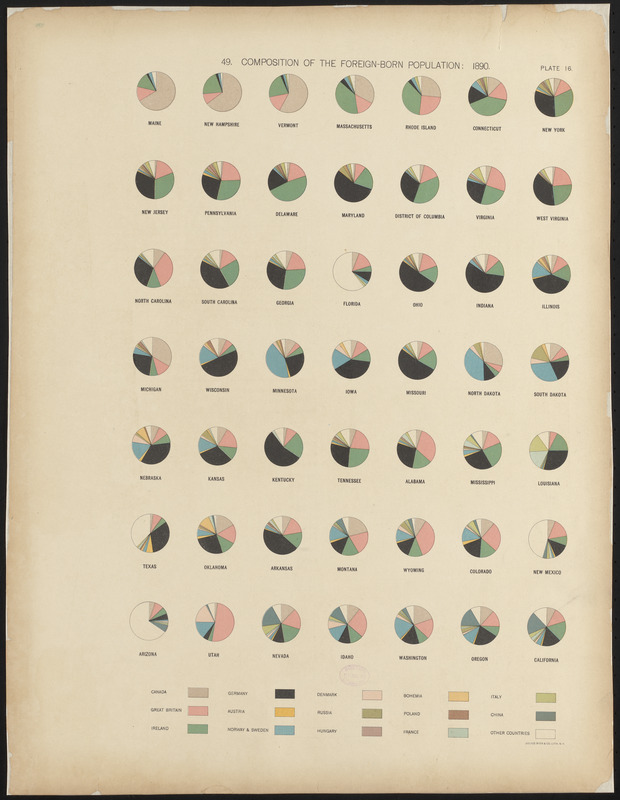

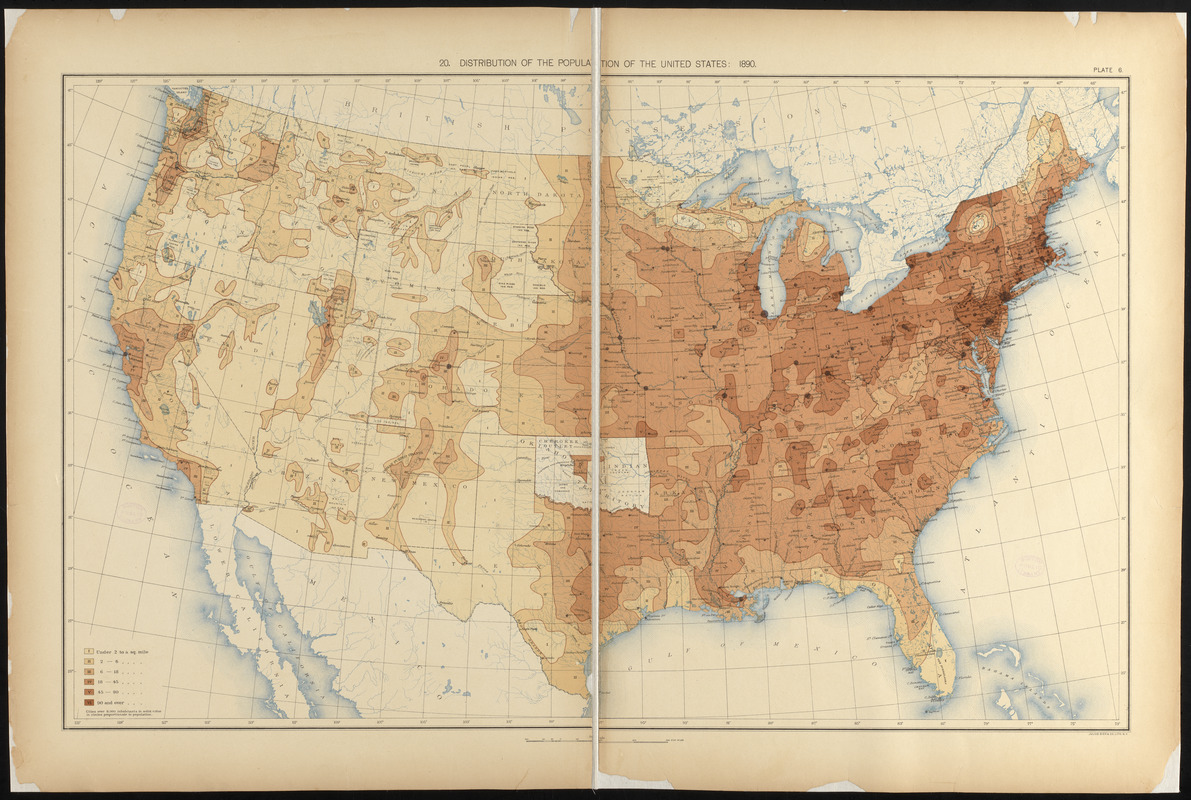

and tabulating vast quantities of geographic information about