Some of the earliest attempts in Boston to re-engineer the environment were directed at the “nuisances” created by the shallow tidelands surrounding the city. Originally located on an island connected to land by a narrow peninsula, Boston’s surrounding salt marshes quickly became a dumping ground for trash, sewage, and toxic industries like tanneries. As residential areas were built on newly-filled neighborhoods in the flats, the “offensive odors” of these defiled landscapes became a problem, as shown in this 1878 Board of Health map. Sanitary engineers, who shared a professional affinity with many early landscape architects, began developing plans to regulate sewage outflows, like this diagram for two potential main sewer routes north and south of the city. These environmental reforms were inspired not only by a dawning recognition of human-led ecological challenges, but also by an attempt to regulate the “moral” character of the city. Clean, tidy neighborhoods well-served by sanitary infrastructure were seen as necessities for a bourgeois vision of domestic order.

Map Showing the Sources of Some of the Offensive Odors Perceived in Boston, 1878

Boston Board of Health

1878

Leventhal Map & Education Center

Boston Main Drainage: Plan Showing Main and Branch Intercepting Sewers Recommended By the Sewerage Commission

Boston Sewerage Commission

1875

Leventhal Map & Education Center

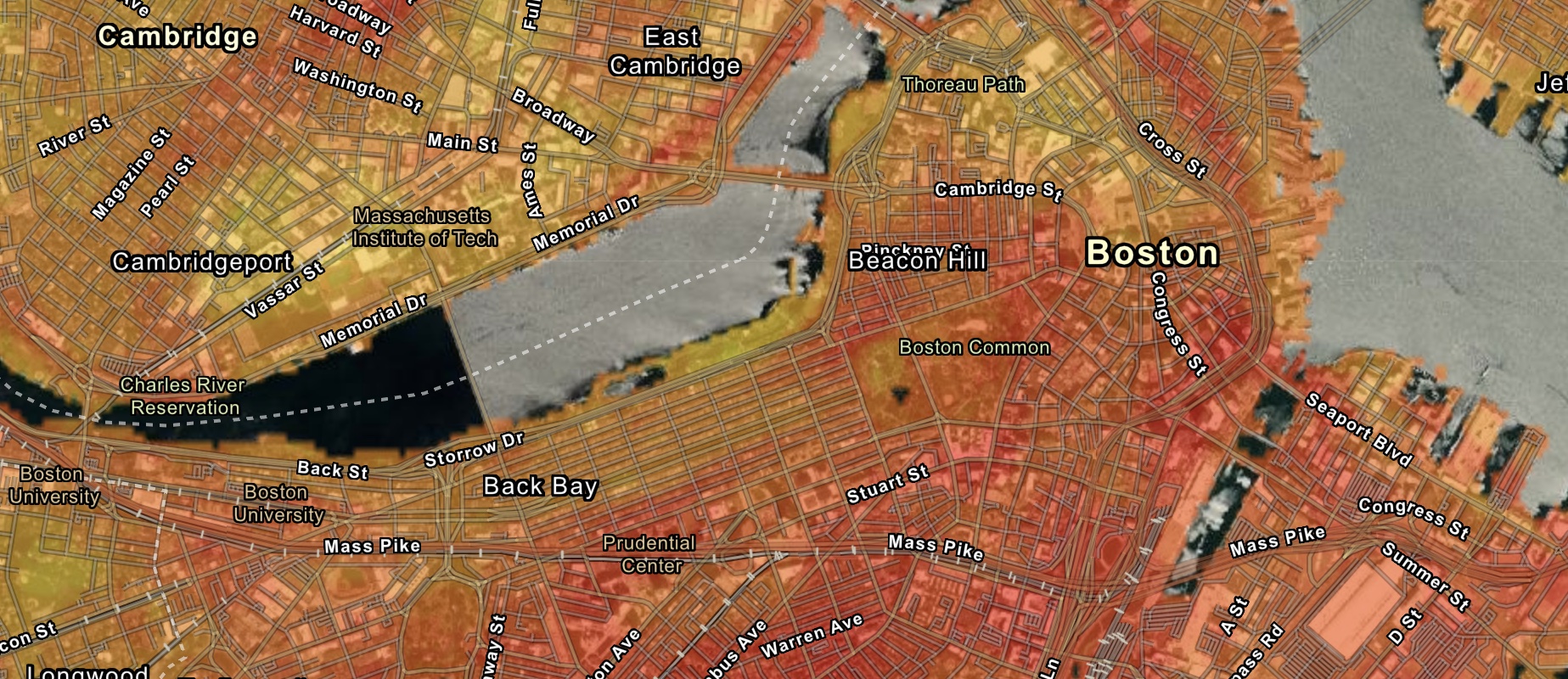

Reconfiguring the natural environment was not just about managing issues like noxious odors. It was also about creating spaces that fit the needs of a particular social order. These maps show how the process of filling in tidal estuaries could serve very different purposes. In the Back Bay neighborhood (where you are now standing), landfill was used to create an élite residential district, well equipped with both cultural facilities, like the Central Library, and attractive landscapes, like the Commonwealth Avenue boulevard and the Back Bay Fens. On the other side of Boston’s original peninsula, the South Bay was put to very different purposes as it was slowly filled in. This 1854 map shows harbor lines—similar to the ones drawn on the Mystic River and Chelsea Creek—that established limits on industrial wharves. Over the years, South Bay would serve as home to industrial docks, rail yards and highway interchanges, and an infamously polluting trash incinerator. Today, the large parking lot in the center of the South Bay shopping mall is a major urban heat island in the summer. The different landscapes of these two filled bays in the 2020s reflects the accumulated history of choices that were made more than a century ago.

Plan of South Bay Showing the Harbor Commissioners Lines

Massachusetts Board of Harbor Commissioners; W. H. Bradley

1854

Leventhal Map & Education Center

Area Plan as of May 1962

Back Bay Association, Inc.

1962, revised 1965, reprint ca. 2000s

Leventhal Map & Education Center