-

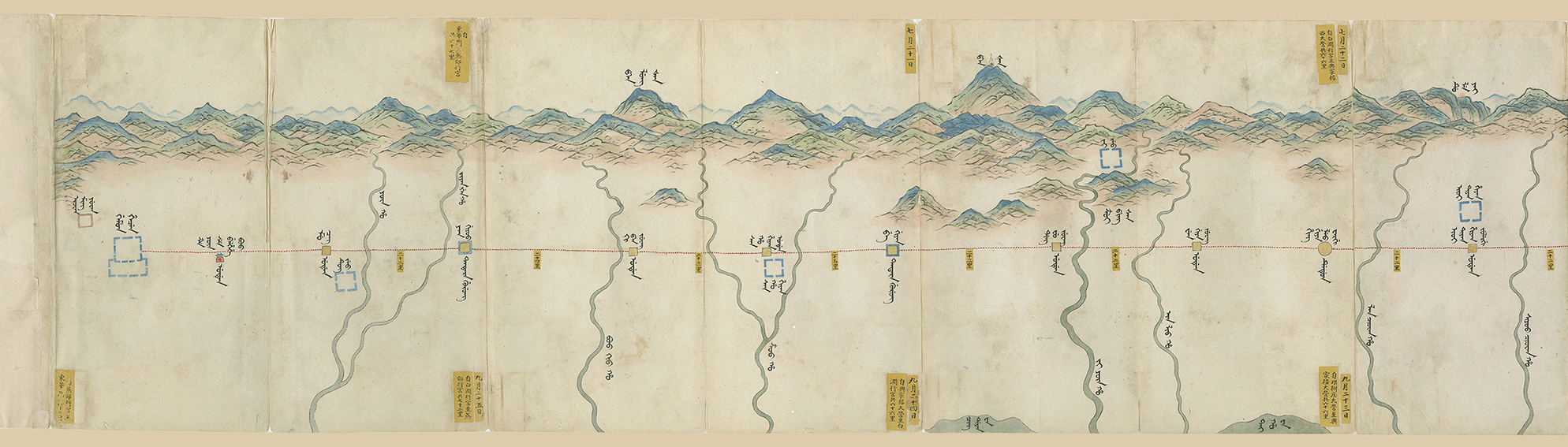

Imperial Palace

-

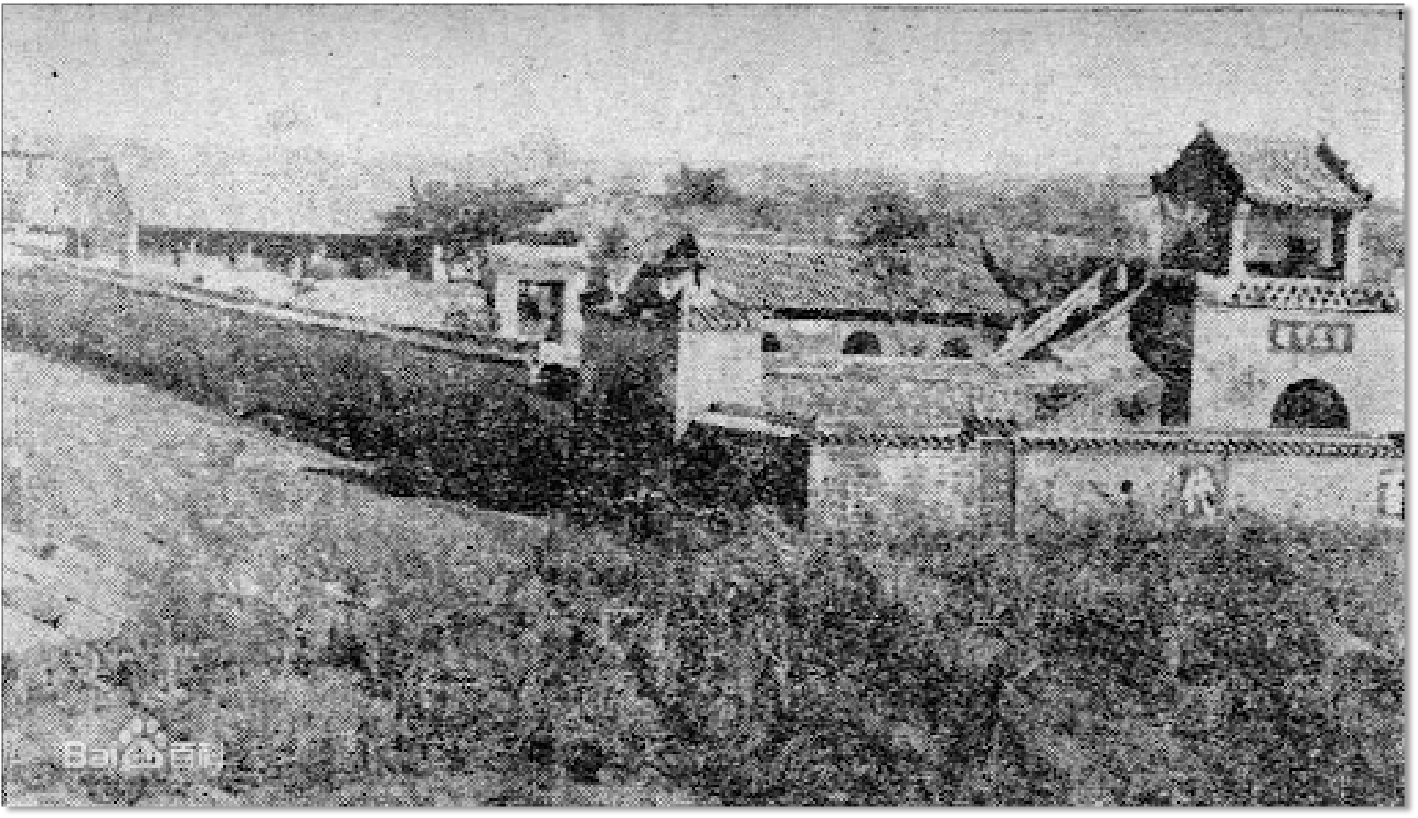

Walled Town

-

Temple

-

Rest Station

-

Travel Palace

-

Path

-

Night Station

-

Distance Marker

-

Ancestral Graves

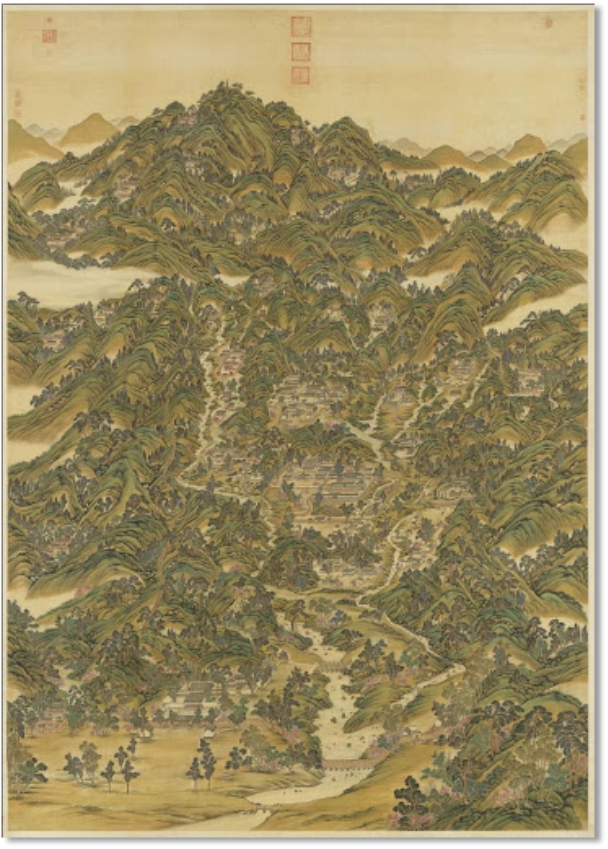

After crossing a couple of rivers, the emperor reached another palace camp at which construction had

recently finished. The Yiqi temple palace camp, in modern day Luan county, Hebei province, features

prominently on the map. The Yiqi temple was not new; it dated from the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD), but

Qing emperors had done extensive reconstruction work on it. The Kangxi emperor, in 1664, had approved the

rebuilding of the temple, and in 1778, the Qianlong emperor had commissioned the construction of the Yiqi

temple for his upcoming eastern tour. The construction work had lasted for about six months and finished

just over two months before the emperor’s arrival. It is perhaps no coincidence that the Manchu name given

to the overnight station, “Yi Ci Temple Reserve House Station” (M. Yi ci miyoo Belhehe boo dedun),

reflects that the building complex includes some added space. This station is illustrated as three red

buildings with a blue roof forming a triangle.

This same symbol of three red buildings is also used to indicate the station right before the Shanhai pass,

also named a Belhehe boo. The full Chinese name for this station is Wenshu’an beiyong fang daying 文殊庵備用房大營

, which means that Belhehe boo is the Manchu equivalent of the Chinese Beiyong fang

, or reserve house. This area is highlighted on the route map and indicates that the emperor toured the

area, stopping at two rest day stations and one overnight station.

After crossing a couple of rivers, the emperor reached another palace camp at which construction had

recently finished. The Yiqi temple palace camp, in modern day Luan county, Hebei province, features

prominently on the map. The Yiqi temple was not new; it dated from the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD), but

Qing emperors had done extensive reconstruction work on it. The Kangxi emperor, in 1664, had approved the

rebuilding of the temple, and in 1778, the Qianlong emperor had commissioned the construction of the Yiqi

temple for his upcoming eastern tour. The construction work had lasted for about six months and finished

just over two months before the emperor’s arrival. It is perhaps no coincidence that the Manchu name given

to the overnight station, “Yi Ci Temple Reserve House Station” (M. Yi ci miyoo Belhehe boo dedun),

reflects that the building complex includes some added space. This station is illustrated as three red

buildings with a blue roof forming a triangle.

This same symbol of three red buildings is also used to indicate the station right before the Shanhai pass,

also named a Belhehe boo. The full Chinese name for this station is Wenshu’an beiyong fang daying 文殊庵備用房大營

, which means that Belhehe boo is the Manchu equivalent of the Chinese Beiyong fang

, or reserve house. This area is highlighted on the route map and indicates that the emperor toured the

area, stopping at two rest day stations and one overnight station.