There were many candy factories in Greater Boston in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. If we walked the streets, we’d smell the sweet air around these places. They’d be pleasant pockets within the overall stench of the city in that time. Using urban atlases of Boston in Atlascope and historical documents in Digital Commonwealth, we can imagine how these industries would shape their neighborhoods. Today, we’ll tour some of those neighborhoods and examine their candy making facilities.

Candy, especially in the nineteenth century, was mainly made of sugar. Much of the sugar at the time was derived from sugar cane. Because of this, candy manufacturing relied on the triangular trade. Triangular trade is the term for the shipping routes and economic relationship among Africa, Europe, and the Americas. The importation of sugar to the American colonies and later the US relied on the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Slave labor in the West Indies produced value and raw materials to make American products.

Candy, especially in the nineteenth century, was mainly made of sugar. Much of the sugar at the time was derived from sugar cane. Because of this, candy manufacturing relied on the triangular trade. Triangular trade is the term for the shipping routes and economic relationship among Africa, Europe, and the Americas. The importation of sugar to the American colonies and later the US relied on the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Slave labor in the West Indies produced value and raw materials to make American products.

We’ll look at five centers of candy production in the Boston area: Baker’s Chocolate in Lower Mills, NECCO in Fort Point Channel, Confectioner’s Row in Cambridge, The Paul Revere House in the North End, and Cox Confectionery in East Boston. This is only a taste of the candy history of the region. Hopefully it whets your appetite for digging into local history and using Atlascope to explore your neighborhood!

1. Baker’s Chocolate, 1220 Adams St, Boston, MA 02124

John Hannon began producing some of the earliest chocolate products in the US in 1765 in Milton, MA. Several years later, the company moved to Dorchester. Chocolate could only be produced in colder weather because of melting. Early mills functioned as grist, wool, paper, and saw mills during other parts of the year.

This handbill for Baker’s is undated, but must have been produced shortly after the 1867 and 1873 European Expositions it references, at which the company won prizes.

Walter Baker was the third generation of Bakers to own the factory — his grandfather had bought it from Hannon’s widow in 1780. The last familial owner of Baker’s Chocolate was Walter’s step-nephew, Henry L. Pierce. Pierce sold out the company for incorporation in 1895. After his death in 1896, the square outside the buildings was named in his memory.

2. NECCO, 27 Melcher St. Boston, MA 02210

This diagram is from the May 12, 1857 patent by the Chase brothers for their Improvements in Machinery for Making Lozenges. This came a decade after their original machine.

NECCO, one of Boston’s most famous confectioners, resulted from a merger of three smaller, older companies. One of these candy manufacturers was Chase & Company, founded by brothers Oliver and Silas Chase. They were later joined by their brother Daniel. Oliver was a pharmacist who, like many others, used sugar as a way to make bitter medicines more palatable.

Oliver Chase invented a lozenge cutter (something like a pasta roller/extruder) in 1847 that opened up the world of candy-making. These disks which he called “Hub wafers” became what we now know as NECCO wafers! US Army rations included the candies in both world wars. Admiral Richard Byrd brought them to the Antarctic as well.

Daniel Chase invented a “Lozenge Printing Machine” that could print text on the chalky candies. This began production of “Conversation Candies,” predecessors of today’s conversation hearts. Daniel moved to Chicago until the Great Fire of 1871, bringing candy-making technology out west. When he moved back, he worked for Fobes, another Boston candy company. Many candy companies, including Chase, were accused of using unsafe additives in their products. Chase & Co. was convicted in 1878 on this charge for their use of Lead (II) Chromate as a yellow coloring agent.

This advertisement highlights the purity of the candy above all else, even putting it before and larger than their spiel about reasonable prices.

On the ground floor of the Horticultural Hall in downtown Boston, Southmayd’s positioned itself as the safe option for candy lovers in this “age of impurities and shams.” It sold a variety of confections from this convenient location. These included gum drops, ice cream candies, and lemon lobster sticks, as well as a refreshing beverage called “Ottawa Beer.”

Chase merged with two other companies, Fobes, Hayward & Co. and Wright & Moody, to become the New England Confectionery Company in 1901. NECCO started operating on Summer St. in 1902.

The company moved to Cambridge in 1927. Manufacturing moved to Revere in 2003. In 2018, the factory closed and brands were sold off to competitors.

3. Confectioner’s Row, Cambridge, MA

The area of Main St. in Cambridge between Kendall Square and Massachusetts Avenue was called “Confectioner’s Row.” This view shows several companies situated off the main drag: Dagget, Page & Shaw, and Durant (or Durand) all contributed to the nickname.

One building at 810 (formerly 814) Main St. in Cambridge still plays a part in the candy industry. Here it is in 1916 as Boston Confectionery Company. Lydian Confectionery and Imperial Chocolate Company merged to form Boston Confectionery.

These cherubic children work together to get at this walnut on a trade card for Close. This design was not unique: at least one other late 19th century confectioner used the same image on his advertising cards.

Sometime between 1930 and 1934, the James O. Welch Co. bought this property. Nabisco purchased Welch in 1963, and then it was acquired by Tootsie Roll Industries. The building is now a part of Cambridge Brands, a subsidiary of Tootsie Roll.

A few blocks over from “Confectioner’s Row” was one of Cambridge’s early candy makers, the George Close Company. A new factory replaced the 1894 building in 1910. It still stands today, serving as affordable housing, and is on the National Register of Historic Places. The company was actually more famous for its collectible baseball cards than any of its candies.

This squirrel is one of many who advertised Squirrel Brand, long before the Squirrel Nut Zippers brought swing back to popular music charts in the 1990s.

Several doors down from the Close Company was Squirrel Brand Nuts. Squirrel Brand made such candies as Squirrel Nut Zippers and Squirrel Nut Caramels. These candies were originally manufactured in Roxbury at 277 Dudley St. by the Austin T. Merrill Company. They eventually became NECCO brands.

4. The Paul Revere House, 19 North Square, Boston, MA 02113

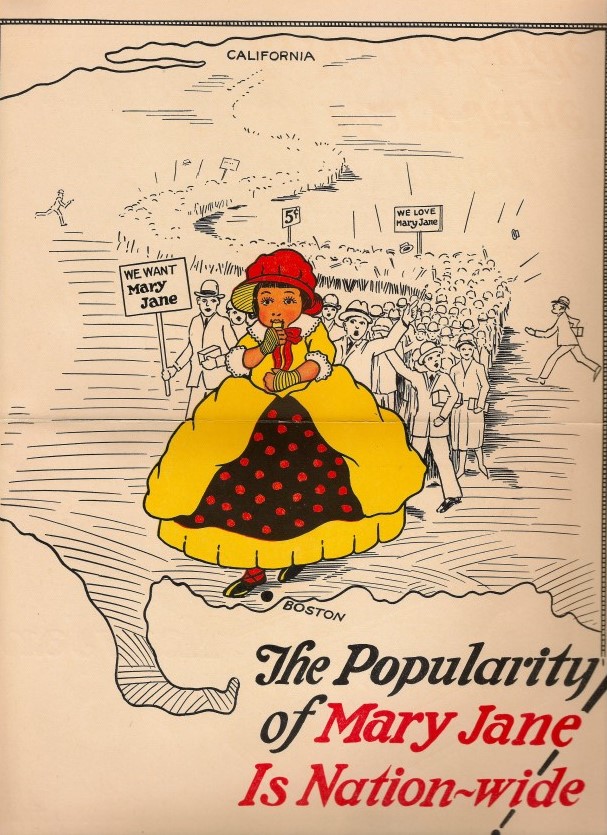

This mappy ad for Mary Jane shows a parade of people stretching across the nation from Boston to California, clamoring for the molasses-based sweet.

One classic sweet that became a NECCO candy in 1989 is the Mary Jane. The peanut butter and molasses treat was made by Charles N. Miller, who appears to have begun his candy career in 1884 while living at 19 North Square. This house is where Paul Revere lived from 1770-1800, and is the site of a historic house museum today. The Revere House is not unique for being both home and factory. Around the same time, there was also a cigar rolling factory in the small building, and at other times a grocery store and a bank. Many of the hundreds of candy factories that existed in Greater Boston near the turn of the century were in buildings where their owners lived. As companies grew, like Chase merging and becoming NECCO, they moved out of their owners’ homes and into larger factory buildings. Smaller confectioners, which used to be quite popular, were forced out of business. Today, the top two confectioners by market share make up over 50% of the market, with several other big companies close behind.

With its molasses base, the Mary Jane’s link to triangular trade and slave labor is a direct one. The North End has yet another molasses connection: the Great Molasses Flood. On January 15, 1919, a tank holding over two million gallons of molasses exploded in the neighborhood, killing twenty-one people and injuring one hundred and fifty. This molasses, however, had been destined for munitions productions, not candy.

5. Cox Confectionery, 150 Orleans St., Boston, MA 02128

Today, this factory building has been converted into condos.

By 1914, candy manufacturing had grown immensely and was the third biggest industry in Boston by value of product. There were seventy-nine confectioners listed in the Boston directory in 1914. Thirty-one of them were in a group called the “New England Confectioner’s [or Confectionery] Club.” By 1950, there were an estimated 140 candy companies in Boston and Cambridge, including this one in East Boston.

This building is still remembered for its earlier usage, like many of the manufacturers on this list. On its address plaque, it says “gumball factory,” some lasting flavor from the early twentieth century.

This Halloween, remember that you can’t eat only your “just desserts,” unless you want to go straight from the candy shop to the dentist next door!

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.